Take a photo of a barcode or cover

for favorite poems, see http://www.poetrypagetat.blogspot.com/

slow-paced

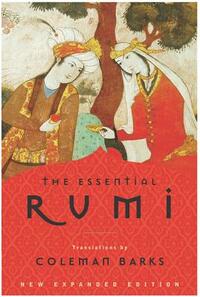

I read Rumi because a couple of years ago I had enjoyed Persian poetry in ‘The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam’ and was now in the mood for something similar.

Except I had never read ‘The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam’, I had read Edward FitzGerald’s translation/paraphrased version of it, much as I didn’t really read any Rumi as much as I read Coleman Barks’ paraphrased version. Barks doesn’t even read Farsi, he made his versions after reading more literal English translations. It’s as much (maybe even more) Barks’ book as it is Rumi’s.

Not that it’s a problem as such, the route of words and thoughts, though interesting and sometimes enlightening, is not as important as whether the words that reached you are effective. It seems particularly apt that a writer who (it would appear) had such a troubled relationship with language and its ability to communicate any truth should be transmitted in such a labyrinthine and torturous manner.

I also probably read this book wrong. I didn’t keep it by my bed and consult individual poems or chapters as the need arose, I read it straight through. I read everything straight through these days, be they novels, textbooks, essays or poetry. Partly this is because I crave that feeling of ending, of having consumed the totality of a work but I also suspected that while I would miss many nuances in individual poems (and I am a pretty poor reader of poems, so that would have happened if I took the work slower) I would appreciate the combined heft of them. I would discover the poems sparking off each other and creating something larger than any individual poem or line. I have to admit this didn’t happen for me and my low rating of this book probably has more to do with the type of person I am and the way I read the book than the quality of the work itself.

Many of my favourite parts of the book were near the beginning, when everything felt fresh and exciting. By the end I was weighed under the metaphors, especially the (extremely oft) repeated ones about reed flutes, eagles, donkeys and oceans.

There’s a brand of tea called ‘Yogi Tea’, most of the flavours don’t contain tea but other herbs and spices - they are pretty tasty for their price range and I enjoy them a lot. The little tags on the teabags contain little bits of ‘wisdom’ which often feel a little lightweight and naff. At work, my identity lanyard has one of these wisdoms attached which reads, ‘not sharing is not caring’, a prime example of the laziness of the wise. My favourite ever read; ‘love is the source of infinity’, which sounds nice and all but is a logical impossibility, infinity can’t have a source.

While most of Rumi is a step up from ‘Yogi Tea’, there was a ‘love is the source of infinity’ inanity to some of it. At one point we are told, “There is a milk fountain inside of you. Don’t walk around with an empty bucket.’ In context of the poem, and the work in general, it falls into one of the many sections that describe the huge reserves of spiritual nourishment that can be found within but are ignored. Even if this one didn’t make that point, there were many (many) other poems that did. Still, as an image, being told I have a milk fountain in me feels faintly ridiculous. I visited a breastfeeding friend while reading this book and gave her that line as she was feeding and she found it equally funny.. we then had a discussion about a London ice cream company’s efforts to sell breast milk ice cream.

At another point I was encouraged to ‘Sniff with your wisdom-nose’. These hyphenated phrases are common in this translation/paraphrasion. There is a spirit-body, a donkey-heart and many other examples in the book. Does Farsi act like German, where words are put together to make new ones or is it Barks’ attempt to say something unsayable? Whatever it is, my wisdom-nose dis blocked and my make-sense-ears can't tune into the melody. Also, the nose is an inherently daft body part and sniffing a silly act. He may have as well talked about the spice-scented farts of the numinous, I can’t promise he didn’t.

Each section had a theme and each had an introduction, welcoming us to the topic and piling on the forthcoming metaphors we were about to meet. In one, bird’s eggs are described as ‘leathery’ - there were more examples of this that I forgot to write down.

It’s an example I see in many works that try and reach beyond the everyday, where a metaphor actively disproves itself. It reminds me of the sermon on the mount when Jesus talks about how people should consider the birds of the air,’they sow not, neither do they reap, nor gather into barns; yet your heavenly Father feedeth them.’ It doesn’t take much considering to realise that birds spend great chunks of their life struggling to feed themselves, they are on a constant search for food. Consider the pigeon, he spends his entire life pecking and scratching and fighting for crumbs of sandwiches, and his feet rot away from standing in his own urine. A metaphor is a dangerous beast, it can bite you back.

To create a hallucinogenic, doorways of reality type effect, this book also often mixes metaphors. Spiritual awakening is compared to great bird that dives into an eternal ocean. The body is a donkey, but the soul is a donkey, but the heart is a donkey, but a donkey can be a donkey, but a friend can be a donkey, but a disliked person can be a donkey - there’s a lot of donkeys. At one point Jesus (who is mentioned a lot, being a revered figure in Islam and all) rides a donkey, at another point a donkey is carried by Jesus. There’s loads of stuff about fish living in the ocean but not having any water to drink - I get the metaphor, that we walk through a spiritual world unknowing - but all I could think is that fish seem to be fine with their deal, there are many fish in the sea.

Perhaps I am merely close-minded to this sort of text. I spent my teen years living in a theological training college where ministers (pastors/vicars whatever you want to call them) are made. I heard a lot of Sohbet, or spiritual conversations and as an atheist who marvels at how much the human race can do without the existence of spirit and God, I find a lot of this stuff flaccid and arbitrary.

That said, when I did connect to this text, it was written with a joy that was intoxicating at times. The desire for friendship, for connection, for a loud party and a quiet moment, for a silly joke or a thoughtful story were all things that I can share and celebrate. The injunction to find the intoxicants that suit us more than wine, that the world has delights filled in every jar and that we should go and be a connoisseur of all that joy, was something that caught me and pulled me along. As such, I enjoyed a great deal of this book and I would be an idiot to say that someone who gains more from it than I did is seeing things that aren’t there. I can’t say this is a bad book in any way, only that it is not the right book for me.

If I want a religious poem of all creation delighting in, and praising God then I'll go back and read Christopher Smart's 'Jubilate Agno' for the umpteenth time.

“Are these enough words or shall I squeeze more juice from this?”

Except I had never read ‘The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam’, I had read Edward FitzGerald’s translation/paraphrased version of it, much as I didn’t really read any Rumi as much as I read Coleman Barks’ paraphrased version. Barks doesn’t even read Farsi, he made his versions after reading more literal English translations. It’s as much (maybe even more) Barks’ book as it is Rumi’s.

Not that it’s a problem as such, the route of words and thoughts, though interesting and sometimes enlightening, is not as important as whether the words that reached you are effective. It seems particularly apt that a writer who (it would appear) had such a troubled relationship with language and its ability to communicate any truth should be transmitted in such a labyrinthine and torturous manner.

I also probably read this book wrong. I didn’t keep it by my bed and consult individual poems or chapters as the need arose, I read it straight through. I read everything straight through these days, be they novels, textbooks, essays or poetry. Partly this is because I crave that feeling of ending, of having consumed the totality of a work but I also suspected that while I would miss many nuances in individual poems (and I am a pretty poor reader of poems, so that would have happened if I took the work slower) I would appreciate the combined heft of them. I would discover the poems sparking off each other and creating something larger than any individual poem or line. I have to admit this didn’t happen for me and my low rating of this book probably has more to do with the type of person I am and the way I read the book than the quality of the work itself.

Many of my favourite parts of the book were near the beginning, when everything felt fresh and exciting. By the end I was weighed under the metaphors, especially the (extremely oft) repeated ones about reed flutes, eagles, donkeys and oceans.

There’s a brand of tea called ‘Yogi Tea’, most of the flavours don’t contain tea but other herbs and spices - they are pretty tasty for their price range and I enjoy them a lot. The little tags on the teabags contain little bits of ‘wisdom’ which often feel a little lightweight and naff. At work, my identity lanyard has one of these wisdoms attached which reads, ‘not sharing is not caring’, a prime example of the laziness of the wise. My favourite ever read; ‘love is the source of infinity’, which sounds nice and all but is a logical impossibility, infinity can’t have a source.

While most of Rumi is a step up from ‘Yogi Tea’, there was a ‘love is the source of infinity’ inanity to some of it. At one point we are told, “There is a milk fountain inside of you. Don’t walk around with an empty bucket.’ In context of the poem, and the work in general, it falls into one of the many sections that describe the huge reserves of spiritual nourishment that can be found within but are ignored. Even if this one didn’t make that point, there were many (many) other poems that did. Still, as an image, being told I have a milk fountain in me feels faintly ridiculous. I visited a breastfeeding friend while reading this book and gave her that line as she was feeding and she found it equally funny.. we then had a discussion about a London ice cream company’s efforts to sell breast milk ice cream.

At another point I was encouraged to ‘Sniff with your wisdom-nose’. These hyphenated phrases are common in this translation/paraphrasion. There is a spirit-body, a donkey-heart and many other examples in the book. Does Farsi act like German, where words are put together to make new ones or is it Barks’ attempt to say something unsayable? Whatever it is, my wisdom-nose dis blocked and my make-sense-ears can't tune into the melody. Also, the nose is an inherently daft body part and sniffing a silly act. He may have as well talked about the spice-scented farts of the numinous, I can’t promise he didn’t.

Each section had a theme and each had an introduction, welcoming us to the topic and piling on the forthcoming metaphors we were about to meet. In one, bird’s eggs are described as ‘leathery’ - there were more examples of this that I forgot to write down.

It’s an example I see in many works that try and reach beyond the everyday, where a metaphor actively disproves itself. It reminds me of the sermon on the mount when Jesus talks about how people should consider the birds of the air,’they sow not, neither do they reap, nor gather into barns; yet your heavenly Father feedeth them.’ It doesn’t take much considering to realise that birds spend great chunks of their life struggling to feed themselves, they are on a constant search for food. Consider the pigeon, he spends his entire life pecking and scratching and fighting for crumbs of sandwiches, and his feet rot away from standing in his own urine. A metaphor is a dangerous beast, it can bite you back.

To create a hallucinogenic, doorways of reality type effect, this book also often mixes metaphors. Spiritual awakening is compared to great bird that dives into an eternal ocean. The body is a donkey, but the soul is a donkey, but the heart is a donkey, but a donkey can be a donkey, but a friend can be a donkey, but a disliked person can be a donkey - there’s a lot of donkeys. At one point Jesus (who is mentioned a lot, being a revered figure in Islam and all) rides a donkey, at another point a donkey is carried by Jesus. There’s loads of stuff about fish living in the ocean but not having any water to drink - I get the metaphor, that we walk through a spiritual world unknowing - but all I could think is that fish seem to be fine with their deal, there are many fish in the sea.

Perhaps I am merely close-minded to this sort of text. I spent my teen years living in a theological training college where ministers (pastors/vicars whatever you want to call them) are made. I heard a lot of Sohbet, or spiritual conversations and as an atheist who marvels at how much the human race can do without the existence of spirit and God, I find a lot of this stuff flaccid and arbitrary.

That said, when I did connect to this text, it was written with a joy that was intoxicating at times. The desire for friendship, for connection, for a loud party and a quiet moment, for a silly joke or a thoughtful story were all things that I can share and celebrate. The injunction to find the intoxicants that suit us more than wine, that the world has delights filled in every jar and that we should go and be a connoisseur of all that joy, was something that caught me and pulled me along. As such, I enjoyed a great deal of this book and I would be an idiot to say that someone who gains more from it than I did is seeing things that aren’t there. I can’t say this is a bad book in any way, only that it is not the right book for me.

If I want a religious poem of all creation delighting in, and praising God then I'll go back and read Christopher Smart's 'Jubilate Agno' for the umpteenth time.

“Are these enough words or shall I squeeze more juice from this?”

inspiring

reflective

slow-paced

Stunning writing, changed my outlook on so many things regarding spirituality, love and friendships and just woow

Poetry of a 13th century Sufi mystic. Absurd and insightful and joyful all rolled together. Read much of it a few poems at a time in the morning before work. Best meditation ever.

Stunning. I read this slowly over many months, at times perplexed by Rumi's words (through translation with some extra-license by Coleman Barks, I've learned in some research) written in the mid-13th century in a language and a land I'm unfamiliar with. But every poem is full of a spirit with which I felt I got to know Rumi through reading this collection. And some poems just left me speechless and stunned. I can hardly wait to begin reading again, and I am grateful I have this volume at arm's reach any time.

Here's a few lines near the end I loved:

"No better love than love with no object,

no more satisfying work than work with no purpose.

If you could give up tricks and cleverness,

that would be the cleverest trick!"

Here's a few lines near the end I loved:

"No better love than love with no object,

no more satisfying work than work with no purpose.

If you could give up tricks and cleverness,

that would be the cleverest trick!"

This thread is all you need to know about this "translated" book.

https://twitter.com/PersianPoetics/status/1261745279860080641?s=19

https://twitter.com/PersianPoetics/status/1261745279860080641?s=19

The most beautiful Poetry collection I've read so far. Definitely worth the read.

slow-paced