Take a photo of a barcode or cover

fast-paced

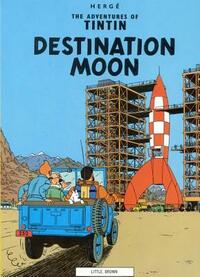

In honor of the first moon landing that happened on this day in 1969, I'm reviewing Destination Moon by Georges Remi Herge. It was first written 19 years before the landing and translated a decade before.

Destination Moon starts where Land of Black Gold ends. Tintin is home but is soon sent to Syldavia to witness a test flight of a moon rocket that will go around to the darkside of the Moon and photograph it.

Destination Moon is better paced than Land of Black Gold, probably because it's not suffering from such a severe editing job. It also provides an interesting look at how space travel was imagined before there was space travel. It's quaint in places but no worse than a typical science fiction of this vintage.

The book balances 1950s hard science fiction with the usual Tintin goofiness. There are gags with Thompson and Thomson. The Captain needs to have his whiskey and his pipe. Snowy gets himself into trouble and Tintin out of it. Meanwhile the rocket ship is your typical pulp science fiction three-point deal.

The book ends with the space program advancing from the unmanned flight to one that will be manned by Tintin (why?), the Captain (again why?), Dr. Calculus (huh?) and some other guy. Of course they're needed to have the adventures in the next book, Explorers on the Moon.

Destination Moon starts where Land of Black Gold ends. Tintin is home but is soon sent to Syldavia to witness a test flight of a moon rocket that will go around to the darkside of the Moon and photograph it.

Destination Moon is better paced than Land of Black Gold, probably because it's not suffering from such a severe editing job. It also provides an interesting look at how space travel was imagined before there was space travel. It's quaint in places but no worse than a typical science fiction of this vintage.

The book balances 1950s hard science fiction with the usual Tintin goofiness. There are gags with Thompson and Thomson. The Captain needs to have his whiskey and his pipe. Snowy gets himself into trouble and Tintin out of it. Meanwhile the rocket ship is your typical pulp science fiction three-point deal.

The book ends with the space program advancing from the unmanned flight to one that will be manned by Tintin (why?), the Captain (again why?), Dr. Calculus (huh?) and some other guy. Of course they're needed to have the adventures in the next book, Explorers on the Moon.

After a minor step backwards with The Land of Black Gold, we're back into classic territory with this one. This installment is flawless - the story, the settings, the humour, everything .Just remember not to tell Professor Calculus he's acting the goat.

The text below is included in ALL of my reviews for the Tintin series. If you've already read it, please proceed to the last part of the review.

I am a lifelong fan of Tintin and Hergé. Tintin was the earliest memory I have of being exposed to books and stories, my dad started to read Tintin to me when I was less than three years old and continued to do so until I learned to read on my own. I have loved these stories my whole life, and I know all of them by heart, in Persian, in English, and in French.

But, as a devout fan, I think it's time to do the hard but right thing: confess that these books are far from perfect. They are full of stereotypes, racist, whitewashed, colonialist, orientalist, you name it. Not to mention a complete lack of female characters (Bianca Castafiore is a mocking relic of the poor dear Maria Callas that Hergé hated, her maid Irma is present in approximately 20 frames, Alcazar's wife also, anyway, there aren't any significant female characters in these books).

In the past few years, I've struggled to decide how I feel about these books. Will I dismiss them? Consider "the time they were written in" and excuse them? Love them in secret? Start disliking them? I don't know. So far I haven't reached a fixed decision, but I will say this: I am aware that these books are problematic. I acknowledge them. I don't stand for the message of some of these books. At the same time, I won't dismiss or hide my love for them because they were an integral part of my growing up memories and fantasies and games, and I do, still, love captain Haddock very much, stupid and ridiculous as he is.

My favorite part about Objectif Lune is the way the captain uses "logarithm" as a swear word. I love it. The logarithm is the height of profanity for sure. :))))

I am a lifelong fan of Tintin and Hergé. Tintin was the earliest memory I have of being exposed to books and stories, my dad started to read Tintin to me when I was less than three years old and continued to do so until I learned to read on my own. I have loved these stories my whole life, and I know all of them by heart, in Persian, in English, and in French.

But, as a devout fan, I think it's time to do the hard but right thing: confess that these books are far from perfect. They are full of stereotypes, racist, whitewashed, colonialist, orientalist, you name it. Not to mention a complete lack of female characters (Bianca Castafiore is a mocking relic of the poor dear Maria Callas that Hergé hated, her maid Irma is present in approximately 20 frames, Alcazar's wife also, anyway, there aren't any significant female characters in these books).

In the past few years, I've struggled to decide how I feel about these books. Will I dismiss them? Consider "the time they were written in" and excuse them? Love them in secret? Start disliking them? I don't know. So far I haven't reached a fixed decision, but I will say this: I am aware that these books are problematic. I acknowledge them. I don't stand for the message of some of these books. At the same time, I won't dismiss or hide my love for them because they were an integral part of my growing up memories and fantasies and games, and I do, still, love captain Haddock very much, stupid and ridiculous as he is.

My favorite part about Objectif Lune is the way the captain uses "logarithm" as a swear word. I love it. The logarithm is the height of profanity for sure. :))))

My mother read me these when I was a child in Brazil in the 1960s. This involved translating them from Portuguese as she read, so I had never actually read them in English until this summer. Like his predecessors, Herge plucks at the leading technology of the time. Poe’s balloons, Verne’s guns, Wells’ electromagnetic waves and now nuclear physics. Herge is surprisingly accurate in his references to enriched Uranium 235 and the use of graphite moderators, but somewhat vaguer in how his nuclear engine actually works. This is particularly so, given that the “supplementary” rocket motor seems to do all the hard work of getting the rocket up into space.

Professor Calculus is even more of a polymath than Cavor, designing every aspect of the rocket and so essential to its success that a bout of concussion-induced amnesia threatens the entire project, where the Apollo mission had thousands of scientists covering all aspects of the science.

As with all Tintin books and some other works of fiction – there is a glib approach to head injuries. Bullets graze skulls, coshes bludgeon into oblivion, and always the heroes emerge immune to the inevitable subdural haematoma or lasting brain injury associated with anything more than a momentary loss of consciousness.

There are no women in Tintin’s lunar adventures – prescient perhaps of the way the role of women got airbrushed out of the Apollo programme. Recently revisited in the book and the film “Hidden Figures”, the role of women doing essential calculations to a high precision and accuracy proved vital to getting Neil Armstrong to the moon and back. It seems particularly fitting that the ambitious programme to return to the moon is named Artemis – after the god Apollo’s extremely capable and independent minded sister.

Professor Calculus is even more of a polymath than Cavor, designing every aspect of the rocket and so essential to its success that a bout of concussion-induced amnesia threatens the entire project, where the Apollo mission had thousands of scientists covering all aspects of the science.

As with all Tintin books and some other works of fiction – there is a glib approach to head injuries. Bullets graze skulls, coshes bludgeon into oblivion, and always the heroes emerge immune to the inevitable subdural haematoma or lasting brain injury associated with anything more than a momentary loss of consciousness.

There are no women in Tintin’s lunar adventures – prescient perhaps of the way the role of women got airbrushed out of the Apollo programme. Recently revisited in the book and the film “Hidden Figures”, the role of women doing essential calculations to a high precision and accuracy proved vital to getting Neil Armstrong to the moon and back. It seems particularly fitting that the ambitious programme to return to the moon is named Artemis – after the god Apollo’s extremely capable and independent minded sister.