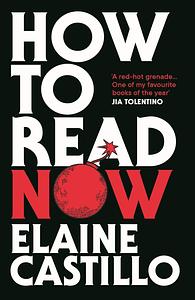

Take a photo of a barcode or cover

A series of essays (no doubt originally commissioned by different publications) that take aim at many of the inherited truths and assumptions made by writers, and which we unwittingly endorse as readers. Of Filipinx heritage, Castillo’s analyses of writers such as Joan Didon. Peter Handke and JK Rowling exposes white, colonialist and cisgendered privilege that assumes all readers share the views they regard as evident truths: their ‘expected readers’. Her work is a guide to what critical reading might mean now, and in particular the ‘unexpected reader’.The reader who is not imagined by the writer, and therefore excluded by them, is exactly that: a failure of imagination. As well as more recent work she reaches back as far as the Odyssey - taking Odysseus down while reclaiming Polyphemus from his received role as a laughably stupid monster.

Threaded through are autobiographical reflections on how reading has shaped her life: from her father pushing Plato, to how reading Henry James caused her to question her whole university course.

Though you’ll perhaps immediately go to the polemical swipes, she finds time to explain why the films of Wong Kar-Wai mean so much to her, why the X-Men and the TV series Watchmen offer so much hope, and how ultimately we might re-engineer a more diverse and inclusive reading culture. You’ll be very well read to have covered everything Castillo does, but she’s an engaging and insightful critic. You won’t agree with everything she says, but you’ll enjoy the debate and learn much from it. Me - I’m working through Wong Kar-Wai’s canon.

Threaded through are autobiographical reflections on how reading has shaped her life: from her father pushing Plato, to how reading Henry James caused her to question her whole university course.

Though you’ll perhaps immediately go to the polemical swipes, she finds time to explain why the films of Wong Kar-Wai mean so much to her, why the X-Men and the TV series Watchmen offer so much hope, and how ultimately we might re-engineer a more diverse and inclusive reading culture. You’ll be very well read to have covered everything Castillo does, but she’s an engaging and insightful critic. You won’t agree with everything she says, but you’ll enjoy the debate and learn much from it. Me - I’m working through Wong Kar-Wai’s canon.

I feel like this book was so impactful when I read it— but I have not thought about it since. Great reflective book.

I found some of the ideas in this collection very useful (thinking through how white and powerful authors fail to imagine an "unexpected reader" for their work and therefore are not open to critiques from this reader, how the narrative of empathy as the primary outcome of reading is fundamentally limited, etc.). However, I found many of the points of critique of literature and media to be shallow and uncomplicated "takes" rather than careful analyses or critiques of the works at hand. In addition to some factually spurious claims (i.e., that José Rizal is one of the only novelist/politicians), I found the language of analysis in this work to be unfortunately limited to the language of the social internet. I hoped Castillo would go beyond such phrases as "oppression chic" to explain what this idea means and how she's deploying it as a critique of our moment -the purported intention of the book- but this was rarely the case. In general, I found this book to be a useful analysis of social processes and injustice in media representation in the U.S. media market, but not a very rigorous or creative analysis of reading or print culture.

Brilliant and funny! Elaine Castillo invites the reader to be critical about the literature they love. She argues so smartly that I even started to question my beloved Jane Austen. Nothing is given, everything is scrutinized. Loved this book!

“I have no desire to write yet another instruction manual for the sociocultural betterment of white readers. I don’t know any writer who, if asked what they wanted their work to do in the world, would reply: “Make better white people.””

“Our practice taught me most of all to read like a free, mysterious person who was encountering free, mysterious things; to value the profound privacy and irregularity of my own thinking; to spend time in my head and the heads of others, and to see myself shimmer in many worlds—to let many worlds shimmer, lively, in me.”

“When artists bemoan the rise of political correctness in our cultural discourse, what they’re really bemoaning is the rise of this unexpected reader. They’re bemoaning the arrival of someone who does not read them the way they expect—often demand—to be read; often someone who has been framed in their work and in their lives as an object, not as a subject.”

“I have no desire to write yet another instruction manual for the sociocultural betterment of white readers. I don’t know any writer who, if asked what they wanted their work to do in the world, would reply: “Make better white people.””

“Our practice taught me most of all to read like a free, mysterious person who was encountering free, mysterious things; to value the profound privacy and irregularity of my own thinking; to spend time in my head and the heads of others, and to see myself shimmer in many worlds—to let many worlds shimmer, lively, in me.”

“When artists bemoan the rise of political correctness in our cultural discourse, what they’re really bemoaning is the rise of this unexpected reader. They’re bemoaning the arrival of someone who does not read them the way they expect—often demand—to be read; often someone who has been framed in their work and in their lives as an object, not as a subject.”

slow-paced

This book made me uncomfortable, in the way things do when you know the person has a point, but admitting it means acknowledging a lot of awkward or painful things. Some essays pulled me in more than others, and there were a number of references that were beyond my scope of knowledge. But there were certainly bits and pieces throughout that made me think.

In the first essay about reading and empathy, the concept of the expected and unexpected readers really resonated. Some readers are not used to being the unexpected reader, they are accustomed to ALWAYS being the target audience and it shows. There are a lot of ideas in this first essay that have been swirling around elsewhere: the over-representation of white people in publishing, the pressure for Black and “ethnic” writers to only write about tragedy and trauma. But the emphasis here on the reader, and on a reader’s responsibility to be open to the world as it is, and not just how they want it to be or how they are comfortable with it being, has me reflecting on my own reading practices and mindset.

A second essay looks around at how different countries reckon with (or fail to grapple with) their relationship with indigenous populations. Other essays look deeper at how labeling reality as “political” allows people to ignore the darker parts of life, and their own privilege. She skewers dynamics within minorities as well, specifically intra-Asian racism, but also points out Black feminists or trans women in feminist spaces.

The final essay begins with Cinderella. And in a nod to the “product of their time” excuse, points out the Charles Perrault lived during a time in France with hyperstereotypical portrayals of their colonies as savages. And which incidentally would have allowed for the introduction of a pumpkin (an American, not European vegetable) into his version of Cinderella.

In the first essay about reading and empathy, the concept of the expected and unexpected readers really resonated. Some readers are not used to being the unexpected reader, they are accustomed to ALWAYS being the target audience and it shows. There are a lot of ideas in this first essay that have been swirling around elsewhere: the over-representation of white people in publishing, the pressure for Black and “ethnic” writers to only write about tragedy and trauma. But the emphasis here on the reader, and on a reader’s responsibility to be open to the world as it is, and not just how they want it to be or how they are comfortable with it being, has me reflecting on my own reading practices and mindset.

A second essay looks around at how different countries reckon with (or fail to grapple with) their relationship with indigenous populations. Other essays look deeper at how labeling reality as “political” allows people to ignore the darker parts of life, and their own privilege. She skewers dynamics within minorities as well, specifically intra-Asian racism, but also points out Black feminists or trans women in feminist spaces.

The final essay begins with Cinderella. And in a nod to the “product of their time” excuse, points out the Charles Perrault lived during a time in France with hyperstereotypical portrayals of their colonies as savages. And which incidentally would have allowed for the introduction of a pumpkin (an American, not European vegetable) into his version of Cinderella.

funny

informative

reflective

slow-paced

Overall I do think this book has merit and I can see why many people enjoy it. My biggest criticisms are:

- The book sometimes reads like an essay with a minimum word requirement.

- The author likes to interject unnecessary commentary in the middle of the sentence. For instance: "I'll paraphrase the hackneyed quote by the equally hackneyed George Santayana (who was often a pretty piss-poor reader of the world himself, and who believed, for example, that intermarriage between superior races- his own- and inferior races-hi- should be prevented): if we don't figure out a different way to read our world, we'll be doomed to keep living in it. (Author's Note, Or A Virgo Clarifies Things, p. 10). Whenever I came across one of these sentences they often came off as all the weaker for the interruption- as if the only way that Castillo could make her point across was to hide it within the sentence.

If you are white, then I would definitely recommend this to you, if you're a person of color, I'd read it if you are looking for a starting place to decolonize your reading.

Minor: Ableism, Genocide, Misogyny, Racism, Sexual violence, Slavery, Grief, Death of parent, Cultural appropriation, Colonisation, War, Classism

challenging

informative

reflective

When I talk about how to read now, I’m not just talking about how to read books now; I’m talking about how to read our world now. How to read films, TV shows, our history, each other. How to dismantle the forms of interpretation we’ve inherited; how those ways of interpreting are everywhere and unseen.

Now more than ever, media literacy and critical thinking are a must. This essay collection engagingly reflects on media from the Odyssey to Cinderella to Asian cinema to monuments of slaveholders. I highlighted so many passages - not just for moments that caused me to pause and reflect, but for simply gorgeous and sharp writing. She writes very specifically to her Filipinx/MFA student/first generation Californian experience while still inviting a larger audience to be challenged by her topics. Intelligent, uncomfortable, snarky, engaging, and so very relevant. I found many connections to the ongoing work of educators to teach absented narratives (while challenging what "representation" means) and how storytelling presents a culture to its consumers.

And the art that I truly love, the art that has saved me, never made me just feel represented. It did not speak to my vanity, my desperation to be seen positively at any cost. It made me feel—solid. It told me I was minor, and showed me my debts. It held me together. And a little like my mom, who went on to have the kid that white woman once wanted to kill: it gave me life. It brought me here. Hi.

How can we think about storytelling not just as a wholly innocent or politically neutral act, but as something that carries within it the capacity for epistemic violence and erasure, a kind of power we’re often reluctant to acknowledge when we want to unilaterally praise the moral good of reading and storytelling?

One too many “virgo bitch”’s for my taste. but a powerful message throughout the book and i was forced to confront uncomfortable feeling especially in the sections i was called out in. and do something about those feelings.

challenging

informative

reflective

slow-paced