Take a photo of a barcode or cover

Some of the most interesting science fiction books these days are those that deal directly with the messed up interaction of our information age, late stage capitalism and democracy. And this book fits nicely in that niche; not only is it about the surveillance state, as the blurb suggests, but it deals a lot with democracy and its problems too. (As such it makes a very interesting companion book to Malka Older's Centenal Cycle and there are certainly parallels between The System and Information)

One of the book's motifs is the combination of steganography and obfuscation to bury useful information in a flood of data. The book somewhat does the same thing. At least two of the story layers don't really add a lot to the core plot. Not to say that they aren't interesting in their own right, but they do lead to a massive 700 page brick of a novel.

But it's a clever book and when everything clicks together at the end, it's very satisfying.

One of the book's motifs is the combination of steganography and obfuscation to bury useful information in a flood of data. The book somewhat does the same thing. At least two of the story layers don't really add a lot to the core plot. Not to say that they aren't interesting in their own right, but they do lead to a massive 700 page brick of a novel.

But it's a clever book and when everything clicks together at the end, it's very satisfying.

I’ve never read another book like this one. It infects the brain and unfolds in the mind uniquely.

The easy way to describe it is a science fiction thriller. But like the plot and theme of the book illustrate, peel off that top onion skin of labels, and you find so many more layers beneath.

The science fiction side was fully realized. Lots of tech and math, but nothing too overwhelming. At times I only caught the spirit, not the letter of the math, but it was enough. Yes, it’s dystopian, but it rises far above most dystopian worlds.

I figured out the “twist” pretty early on — I’m not a reader of thrillers, but all the big ones now have twists, so I assume that’s what it is — and the foreknowledge didn’t mitigate the horror and complexity once it was finally revealed.

I’m now listening to JS Bach, which is something I never do. I’m trying to get my untrained ears to examine the counterpoint, which I’d never thought I’d ever do. This book won’t just stick with me, it has changed me. As the author intended.

The easy way to describe it is a science fiction thriller. But like the plot and theme of the book illustrate, peel off that top onion skin of labels, and you find so many more layers beneath.

The science fiction side was fully realized. Lots of tech and math, but nothing too overwhelming. At times I only caught the spirit, not the letter of the math, but it was enough. Yes, it’s dystopian, but it rises far above most dystopian worlds.

I figured out the “twist” pretty early on — I’m not a reader of thrillers, but all the big ones now have twists, so I assume that’s what it is — and the foreknowledge didn’t mitigate the horror and complexity once it was finally revealed.

I’m now listening to JS Bach, which is something I never do. I’m trying to get my untrained ears to examine the counterpoint, which I’d never thought I’d ever do. This book won’t just stick with me, it has changed me. As the author intended.

Vast and bewildering and overlong and angry but also thought-provoking and with flashes of humor and immersive and a call to sit up and pay attention to the world around you. A book about the power of books, and the special bond between author and audience.

One of the most intricate and best-written books I've ever read. I read it over the course of a little over a year, picking it up and putting it back down, never our of boredom, just out of knowing that it was not a process to rush.

I'm not sure how to verbalize my thoughts on this book. I feel as though the universe were unzipped and then stitched back together in a different pattern. I feel as though I have just witnessed the solving of a logic puzzle in the format of a novel. I feel both energized and deeply inadequate as a writer.

I'm not sure how to verbalize my thoughts on this book. I feel as though the universe were unzipped and then stitched back together in a different pattern. I feel as though I have just witnessed the solving of a logic puzzle in the format of a novel. I feel both energized and deeply inadequate as a writer.

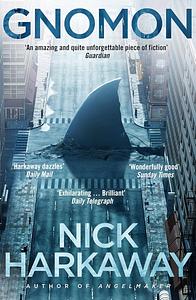

Yes, Gnomon is a behemoth of a book, one I am glad I saved for the beginning of March Break. Even then it took me several days to get through it. Nick Harkaway’s story is intricately layered and nested, and while I wasn’t sure about it at first, the more time I spent with it, the more I came to appreciate and enjoy its construction. Gnomon is a lot of things, and a simple summary won’t really cut it. Let me take you on my personal journey of understanding this book. If you read it, your journey might be quite different, and your mileage, of course, may vary.

We start with what seems like a mystery set in a near-future where the UK is even more of a surveillance society than it currently is. The System is an omnipresent AI built from a collection of self-correcting algorithms. The Witness is the System’s data collection/feedback component, i.e., it monitors what people do, investigates when crimes happen, and provides reports. Mielikki Neith is one of the human cogs in this machine. As an Inspector for the Witness, she goes anywhere that is necessary to collect information, process it with her meatbrain, and then integrate it with whatever else the Witness has gleaned from other sources. Neither the Witness nor the System are conscious, in any meaningful sense, though indeed one of the larger questions Harkaway would like us to ruminate upon is why we are so certain we’re conscious and the System is not.

So at first, the book seems like a story about mysteries in a surveillance state, and therefore, a polemic against such a dystopia. Neith is a believer in the System, yet signs point to someone tampering with what is supposedly tamper-proof. Had Harkaway stopped here, I think he could have a perfectly good sci-fi thriller on his hands. But, of course, he didn’t. Neith has to unpack the memories recorded during the interrogation of Diana Hunter. Hunter’s death during this interrogation is the central mystery. But the memories are really stories, stories of the lives of people who might never have existed. Are they merely Hunter’s attempts to resist interrogation by neural probe? Or is there more going on here?

Harkaway seems to be asking questions not just about how willing we are to tolerate invasive surveillance and a dearth of privacy but also how we feel about technology in general. This is my favourite quotation:

The stories that Harkaway tells through Hunter’s counter-interrogation narratives are all about the ways in which we confront and use (or abuse) technology. The quotation above is from Berihun Bekele’s narrative. He is an old man learning new technology so he can apply his art to his granddaughter’s immersive video game project. That first sentence in particular gets at me, because I think it hits a truth easily overlooked by a lot of superficial analysis of technological progress these days. We talk about older generations having a hard time adapting to “computers”, but that isn’t the point. If anything, computers are old news. Computers are everywhere, and they are nowhere, in the sense that we almost don’t see them if we don’t look hard enough.

We might not have a comprehensive AI System yet, but in many ways we are close. I think a lot of us—of many generations—have this mental picture of the world as somehow being like it was in 1900, just with high speed Internet and digital cameras. Except it is nothing like that, because computers have literally infiltrated and changed every aspect of our lives. Modernity isn’t about computers. Modernity is about the thinking in a society where computers run things in the background.

This theme resounds throughout all of the narratives. Gnomon reminds me, in structure and style, of many things—Cloud Atlas, William Gibson, but above all else, Umberto Eco. This has the playfully meta-fictional awareness of Foucault’s Pendulum and the deeply unsettling mystery vibe of The Name of the Rose. Like Eco, Harkaway likes to play with language and semiotics, as evidenced by the way the title word weaves throughout the narratives, and certain phrases or motifs, like Fire Judges, Firespine, etc., repeat in different constructs. Like Eco, Harkaway seems to have consumed this vast gestalt of human history and philosophy and synthesized it into a fascinating, thought-provoking work of art.

Honestly, the ending was slightly disappointing. As the narratives collapse inwards on one another and we return to “reality”, Harkaway seems to shift the focus of the main story to the question of whether or not the System is a Good Thing and who, if anyone, should have the right to adjust it. In some ways, this seems to simplify the book more than I would like. Still, I respect the questions he is asking here. While he largely sidesteps the “all-powerful AI monitors and corrects the behaviour of society but, shock, turns out to be evil” trope, he does succeed in pointing out that any AI-powered attempt at demarchy is probably futile in the sense that, at some level, humans are going to screw it up. The only way to prevent that is to wrest power completely from humans (and then it isn’t really demarchy at all any more).

If you are a looking for a straightforward narrative here, whether it’s science fiction or mystery or crime or whatever, you will be disappointed. Gnomon demands that you sink your teeth into it, think on it, scrutinize it carefully. Do so, and you will hopefully be rewarded with a very thoughtful story. But if that isn’t your thing, or you’re not in the mood, I suspect you will be left quite frustrated, confused, or just bored. Gnomon lacks the humorous absurdism of Harkaway’s first two novels, The Gone-Away World and Angelmaker, which were probably my favourites for that reason. It shares a little more in common with Tigerman in the way Harkaway pulls from pop culture ideas and spins them out into serious social considerations. If anything, this novel confirms that every book Harkaway produces is going to be new and very different, an evolution, each one building on the last. While I wouldn’t call this my favourite, it was definitely an excellent vacation read, so fulfilling in its scope and themes.

We start with what seems like a mystery set in a near-future where the UK is even more of a surveillance society than it currently is. The System is an omnipresent AI built from a collection of self-correcting algorithms. The Witness is the System’s data collection/feedback component, i.e., it monitors what people do, investigates when crimes happen, and provides reports. Mielikki Neith is one of the human cogs in this machine. As an Inspector for the Witness, she goes anywhere that is necessary to collect information, process it with her meatbrain, and then integrate it with whatever else the Witness has gleaned from other sources. Neither the Witness nor the System are conscious, in any meaningful sense, though indeed one of the larger questions Harkaway would like us to ruminate upon is why we are so certain we’re conscious and the System is not.

So at first, the book seems like a story about mysteries in a surveillance state, and therefore, a polemic against such a dystopia. Neith is a believer in the System, yet signs point to someone tampering with what is supposedly tamper-proof. Had Harkaway stopped here, I think he could have a perfectly good sci-fi thriller on his hands. But, of course, he didn’t. Neith has to unpack the memories recorded during the interrogation of Diana Hunter. Hunter’s death during this interrogation is the central mystery. But the memories are really stories, stories of the lives of people who might never have existed. Are they merely Hunter’s attempts to resist interrogation by neural probe? Or is there more going on here?

Harkaway seems to be asking questions not just about how willing we are to tolerate invasive surveillance and a dearth of privacy but also how we feel about technology in general. This is my favourite quotation:

… it had almost nothing to do with computers, the modernity I was trying to understand. Computers were the bones, but imagination, ambition and possibility were the blood. These kids, they simply did not accept that the world as it is has any special gravity, any hold upon us. If something was wrong, if it was bad, then that something was to be fixed, not endured. Where my generation reached for philosophy and the virtue of suffering, they reached instead for science and technology and they actually did something about the beggar in the street, the woman in the wheelchair. They got on with it. It wasn’t that they had no sense of spirit or depth. Rather they reserved it for the truly wondrous, and for everything else they made tools.

The stories that Harkaway tells through Hunter’s counter-interrogation narratives are all about the ways in which we confront and use (or abuse) technology. The quotation above is from Berihun Bekele’s narrative. He is an old man learning new technology so he can apply his art to his granddaughter’s immersive video game project. That first sentence in particular gets at me, because I think it hits a truth easily overlooked by a lot of superficial analysis of technological progress these days. We talk about older generations having a hard time adapting to “computers”, but that isn’t the point. If anything, computers are old news. Computers are everywhere, and they are nowhere, in the sense that we almost don’t see them if we don’t look hard enough.

We might not have a comprehensive AI System yet, but in many ways we are close. I think a lot of us—of many generations—have this mental picture of the world as somehow being like it was in 1900, just with high speed Internet and digital cameras. Except it is nothing like that, because computers have literally infiltrated and changed every aspect of our lives. Modernity isn’t about computers. Modernity is about the thinking in a society where computers run things in the background.

This theme resounds throughout all of the narratives. Gnomon reminds me, in structure and style, of many things—Cloud Atlas, William Gibson, but above all else, Umberto Eco. This has the playfully meta-fictional awareness of Foucault’s Pendulum and the deeply unsettling mystery vibe of The Name of the Rose. Like Eco, Harkaway likes to play with language and semiotics, as evidenced by the way the title word weaves throughout the narratives, and certain phrases or motifs, like Fire Judges, Firespine, etc., repeat in different constructs. Like Eco, Harkaway seems to have consumed this vast gestalt of human history and philosophy and synthesized it into a fascinating, thought-provoking work of art.

Honestly, the ending was slightly disappointing. As the narratives collapse inwards on one another and we return to “reality”, Harkaway seems to shift the focus of the main story to the question of whether or not the System is a Good Thing and who, if anyone, should have the right to adjust it. In some ways, this seems to simplify the book more than I would like. Still, I respect the questions he is asking here. While he largely sidesteps the “all-powerful AI monitors and corrects the behaviour of society but, shock, turns out to be evil” trope, he does succeed in pointing out that any AI-powered attempt at demarchy is probably futile in the sense that, at some level, humans are going to screw it up. The only way to prevent that is to wrest power completely from humans (and then it isn’t really demarchy at all any more).

If you are a looking for a straightforward narrative here, whether it’s science fiction or mystery or crime or whatever, you will be disappointed. Gnomon demands that you sink your teeth into it, think on it, scrutinize it carefully. Do so, and you will hopefully be rewarded with a very thoughtful story. But if that isn’t your thing, or you’re not in the mood, I suspect you will be left quite frustrated, confused, or just bored. Gnomon lacks the humorous absurdism of Harkaway’s first two novels, The Gone-Away World and Angelmaker, which were probably my favourites for that reason. It shares a little more in common with Tigerman in the way Harkaway pulls from pop culture ideas and spins them out into serious social considerations. If anything, this novel confirms that every book Harkaway produces is going to be new and very different, an evolution, each one building on the last. While I wouldn’t call this my favourite, it was definitely an excellent vacation read, so fulfilling in its scope and themes.

I am Gnomon and so is my wife.

This book has everything: near future cyberpunk dystopian noir detective, surveillance states, choice architecture, participatory democracy, memory replay, Roman alchemy, the financial crisis, mmorpgs, identity modelling, universe breaking post human give minds, lots and lots of sharks and more.

It is also the foundational text of a mystic cult for the cyber era and worthy of study and contemplation.

Imagine Orwell rewrote Cloud Atlas with help from Philip K Dick and Robert Anton Wilson.

This book has everything: near future cyberpunk dystopian noir detective, surveillance states, choice architecture, participatory democracy, memory replay, Roman alchemy, the financial crisis, mmorpgs, identity modelling, universe breaking post human give minds, lots and lots of sharks and more.

It is also the foundational text of a mystic cult for the cyber era and worthy of study and contemplation.

Imagine Orwell rewrote Cloud Atlas with help from Philip K Dick and Robert Anton Wilson.

It’s just print on a page, but boy, I felt like I’d dived head first into a multisensory vat of electric boogaloo goo. Don’t be daunted by the size of the book! It’s worth every sentence to get to the brain-boggling conclusion.

Reminded me of the Raw Shark Texts but more baroque & more frightening. It scared me a lot. But also it was just too intense & too layered & too complicated.

It's only January and already I've had my head wrecked by this monster, chewed up and spat out by its sharp multi-layered convolutions. In a future British State of total surveillance, a woman dies under interrogation. An Investigator looks into the case, but in reviewing the interrogation - which involves one's entire life being scanned via invasive brain-reading machinery - she discovers not one life but five, and as she immerses herself in a a series of increasingly impossible stories that may be a kind of camouflage or may be a kind of trap, we find ourselves on a deep dive into human consciousness and identity, not to mention ideas of freedom and the consequences of technological innovations.

It's a big, dense, intense, sprawling book, and the one where Harkaway completes the transformation from the clever-clever silly-satirist-with-a-heart of The Gone Away World to something terrifyingly literate and intelligent, grappling with enormous ideas that he inserts carefully into our heads so they can cause all sorts of trouble.

It's a big, dense, intense, sprawling book, and the one where Harkaway completes the transformation from the clever-clever silly-satirist-with-a-heart of The Gone Away World to something terrifyingly literate and intelligent, grappling with enormous ideas that he inserts carefully into our heads so they can cause all sorts of trouble.

I went into this with expecting something that was impenetrable and "worthy". I fully expected to struggle along with it for a few days then give up.

What I got was something really rather special and quite probably my book of the year.

The writing is fluid, poetic and at times very funny. The pacing is perfect - every time i was getting fatigued (it's a big, heavy hardback) something would happen that made me go "woah!" and keep reading.

The characters are all really well defined and the changing relationships between them are brilliant.

The plot is huge, with so many layers of complexity it's impossible to pick up on everything in one reading - there were sections I read a few times and I fully expect to go back and re-read the full thing in the future.

It does take brain cells and focus to understand and enjoy this but at no point does it make you feel stupid or assume you have prior knowledge of anything.

Well worth reading.

What I got was something really rather special and quite probably my book of the year.

The writing is fluid, poetic and at times very funny. The pacing is perfect - every time i was getting fatigued (it's a big, heavy hardback) something would happen that made me go "woah!" and keep reading.

The characters are all really well defined and the changing relationships between them are brilliant.

The plot is huge, with so many layers of complexity it's impossible to pick up on everything in one reading - there were sections I read a few times and I fully expect to go back and re-read the full thing in the future.

It does take brain cells and focus to understand and enjoy this but at no point does it make you feel stupid or assume you have prior knowledge of anything.

Well worth reading.