Take a photo of a barcode or cover

E. M. Forster sets a crucial chapter of A Room with a View in the Piazza della Signoria in Florence. Forster's heroine, Lucy Honeychurch, witnesses a trivial but fatal dispute between two men in which knives are instantly drawn. Lucy, an Edwardian girl full of sensibility, is horrified by the blood gushing from the mouth of the dying man and falls in a swoon. Fortunately there is a michaelangelesque character standing nearby, ready to catch her in his powerful arms.

I was in Florence when I was reading Forster's novel so I took a walk around the Piazza della Signoria soon after I'd read the episode of the knife fight, trying to imagine the scene. According to Forster, Lucy was standing by the Neptune Fountain. On Lucy's right-hand side would have been the various statues that still stand in front of the Palazzo Vecchio and along the side of the Uffizi Gallery: Michaelangelo's enormous David with his powerful arm raised, coolly estimating the best angle from which to fling his stone at Goliath; Baccio Bandinelli's colossal Hercules, brutally beating his enemy Cacus with a club; Donatello's Judith holding the bloodied body of Holofernes; and several other large marble pieces, all depicting violent scenes. But among all that monumental marble, one piece of statuary stands out: a relatively small bronze figure with a sword in his hand. This is Perseus trampling the body of the Medusa while triumphantly raising the severed head high in the air. The bronze is remarkable for many reasons but in particular for the way the stream of blood gushes from the head. I think E. M. Forster must have stood exactly where I was standing when he first imagined that scene, and must have had the Perseus in mind.

view image:

That wasn't my first visit to the Piazza. I had walked around that area on my first day in Florence and had already been impressed by the bronze Perseus not only because of the contrast with the other statues but because of the finesse of the figure. It truly is a beautiful piece of work though slightly less than life-size. Very few tourists stopped to look at it when I was there; the much more celebrated David garners all the attention.

.....……………………………………………………………………

I started Benvenuto Cellini's autobiography about a week before my trip to Florence, hoping to get a flavor of the Renaissance city from a contemporary account. Cellini was born in Florence in 1500 so his life spanned three-quarters of the famous century. He tells us that he was apprenticed to a goldsmith at a young age and that he worked on commissions for many powerful people. His early work was carried out mainly for the Medici family in Florence, but after a dispute in which he killed a man, he was obliged to flee the city. He wasn't yet twenty.

After that unfortunate episode, Cellini set out for Rome where he worked for the Medici pope, Leo X, and for Leo's successor and cousin, Giulio de' Medici, who became pope in 1523 and who commissioned Michaelangelo to paint 'The Last Judgement' in the Sistine Chapel around the same time.

As well as setting jewels and minting coins for the pope, Cellini served as a soldier during the Sack of Rome in 1527 and later spent time as a prisoner in the Castel Sant'Angelo for knifing a man in a dispute; he'd made many enemies in Rome by then. He escaped from the Castello in a dramatic escapade which involved knotted bedsheets and a broken leg, and took refuge in France in the court of François I. The French King had welcomed Leonardo da Vinci some years before when he too had run out of friends in Italy. Cellini spent quite a few years in France in the King's service, working on small decorative objects in gold and silver such as tableware, jewelry, and commemorative coins and medals.

..........……………………………………………………………

By the time I reached Florence, I was two thirds of the way through Benvenuto Cellini's excellent account of his life, and though I enjoyed reading about his adventures, I despaired of him ever returning to his native city. I half wished I'd chosen a book about someone who'd spent more of his life in the Tuscan capital, and was glad I'd taken Forster's book along since it, at least, was set in Florence.

Cellini was forty-five at this point in his tumultuous career, and was making as many enemies in France as he'd made in Italy. He had also fallen out with the King over the terms of his contract so, much to my relief, he turned his horse in the direction of Italy hoping to regain the patronage of his first employers, the Florentine Medicis.

Benvenuto and I were now finally in the same place.

Cellini's return to his native city reawakened his early but as yet unrealized ambition: he'd worked as a goldsmith most of his life but he longed to produce a work on a larger scale so when Duke Pier Luigi de' Medici asked about his projects, Cellini answered that he "would willingly make a great statue in marble or bronze for his fine piazza." The Duke decided that he would like a statue of Perseus, in bronze.

I read that passage the evening after I arrived in Florence, and the very day I'd seen the Perseus statue in the Piazza Della Signoria for the first time. There is no plaque on the statue, nothing to indicate who created it, so discovering that the statue that had entranced me was by Cellini was a truly extraordinary moment. Reading has few greater pleasures.

While I'd expected to see small objects by Cellini in gold and silver in the museum, I'd never expected him to have produced a statue in bronze. The description of the casting of the Perseus is by far the most interesting chapter in the autobiography - I'd recommend this book for that section alone. One of the challenges was heating the alloy sufficiently so that it would flow all the way along the upraised arm of the mould and into the severed head. The parallels between the blood pouring from the Medusa's head and the liquid alloy are hard to ignore - the streams of blood would have been the most difficult area for the molten bronze to reach. But Cellini was always motivated by challenges and used all his ingenuity to overcome such difficulties.

view image:

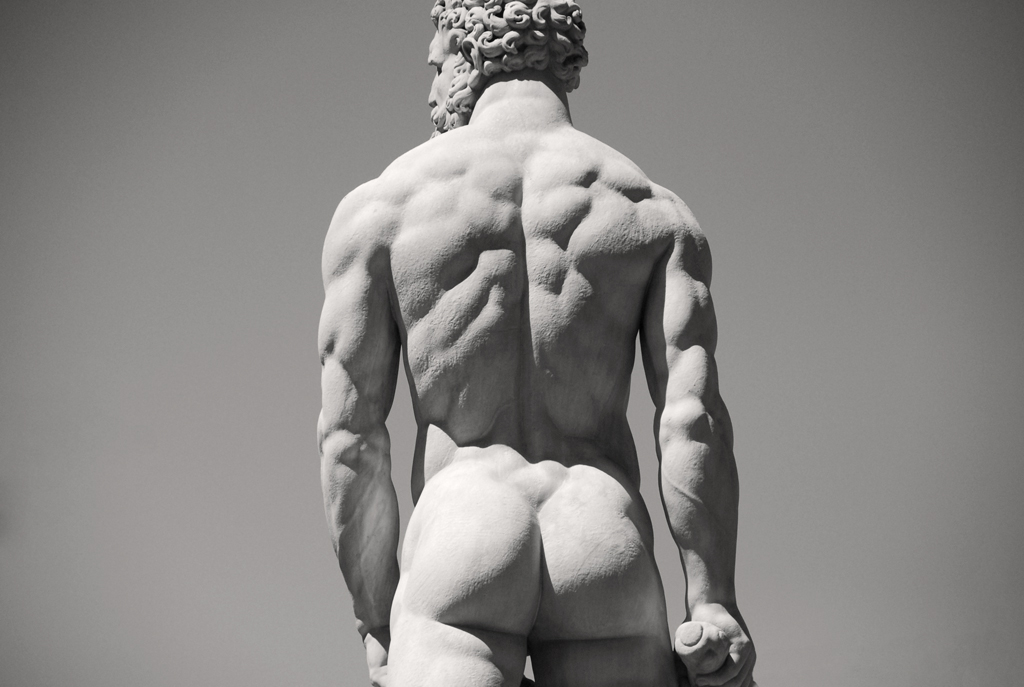

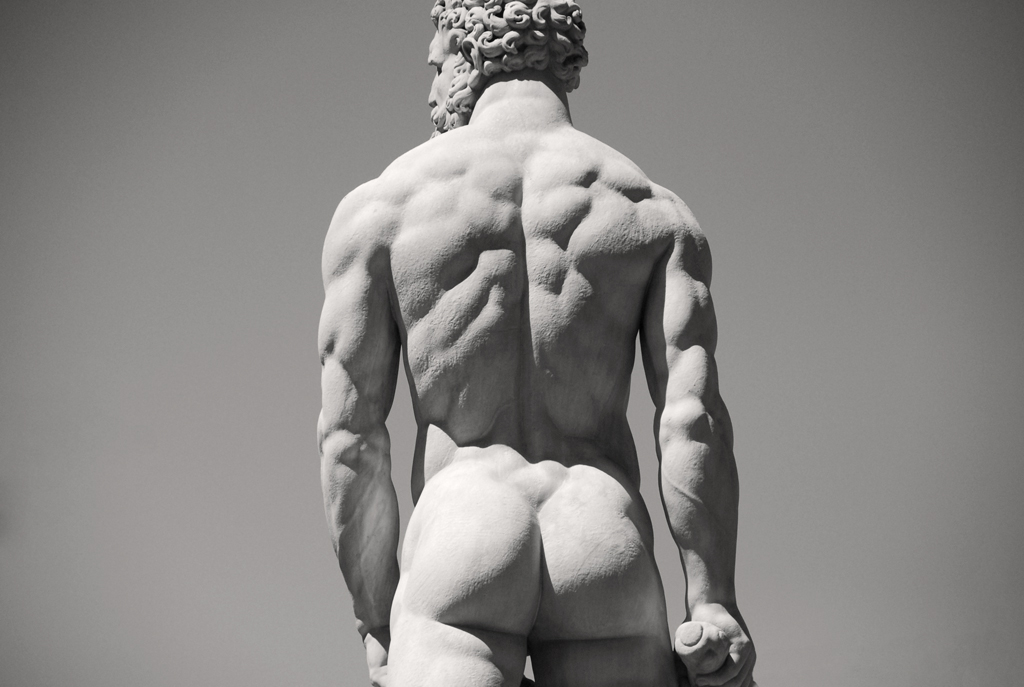

However, the newly minted sculptor wasn't satisfied with a commission for a work in bronze; he longed to work in marble. From then on, he put himself forward for any of the Medici commissions involving marble; he was determined to compete with the major Florentine sculptors of the day, Bartolomeo Ammanato and Baccio Bandinelli. When the Duke was planning the enormous Neptune for the fountain in the Piazza della Signoria, the exact location of Forster's dramatic scene, Cellini submitted a design. The Duke gave the commission to Ammanato.

view image:

However, it was Baccio Bandinelli, who had created the Hercules and Cacus sculpture on the Piazza in 1535, who became Cellini's greatest rival during subsequent marble commissions. Cellini rarely praises the work of other artists, with the exception of Michaelangelo Buonarroti, but he is particularly critical of Bandinelli's Hercules, as he tells the Duke:

view image:

'...if you were to shave off Hercules's hair, there wouldn't be any noddle left to hold the brains; and as for his face, one can't tell whether it's a man's or that of some cross between a lion and an ox...moreover, its great hideous shoulders are like nothing so much as two pommels of an ass's pack-saddle; and the breasts and all the muscles are not modelled from a man, but from a great sack of melons.."

view image:

In spite of Cellini's best efforts, Bandinelli retained the Duke's favour but Cellini received three commissions for works in marble after his rival's sudden death: a Narcissus and a Ganymede, both done in the late 1540s, and an Apollo with Hyacinth from 1550. He also made a Christ figure in marble for the Duke's wife.

view image:

Around this time, Cellini turned his attention to investing his earnings and acquiring property; he had fallen out of favor with the Medicis in any case and received no more commissions.

He began writing his autobiography in 1558 and continued until 1565 when he embarked on a Treatise on Goldsmithing and Sculpture. He died in 1571.

......……………………………………………………………………

I crossed the famous Ponte Vecchio which spans the Arno several times during my stay in Florence. It was there that Forster's heroine Lucy was taken to recover from the trauma of seeing so much blood spilled on the Piazza. Today, it's a frantically busy place full of vendors and tourists, the kind of place I tend to hurry through, so it wasn't until the final day of my Florence visit that I noticed the commemorative bust at one end of the bridge.

I stepped closer to see who was represented there: none other than Benvenuto Cellini.

view image:

I was in Florence when I was reading Forster's novel so I took a walk around the Piazza della Signoria soon after I'd read the episode of the knife fight, trying to imagine the scene. According to Forster, Lucy was standing by the Neptune Fountain. On Lucy's right-hand side would have been the various statues that still stand in front of the Palazzo Vecchio and along the side of the Uffizi Gallery: Michaelangelo's enormous David with his powerful arm raised, coolly estimating the best angle from which to fling his stone at Goliath; Baccio Bandinelli's colossal Hercules, brutally beating his enemy Cacus with a club; Donatello's Judith holding the bloodied body of Holofernes; and several other large marble pieces, all depicting violent scenes. But among all that monumental marble, one piece of statuary stands out: a relatively small bronze figure with a sword in his hand. This is Perseus trampling the body of the Medusa while triumphantly raising the severed head high in the air. The bronze is remarkable for many reasons but in particular for the way the stream of blood gushes from the head. I think E. M. Forster must have stood exactly where I was standing when he first imagined that scene, and must have had the Perseus in mind.

view image:

Spoiler

That wasn't my first visit to the Piazza. I had walked around that area on my first day in Florence and had already been impressed by the bronze Perseus not only because of the contrast with the other statues but because of the finesse of the figure. It truly is a beautiful piece of work though slightly less than life-size. Very few tourists stopped to look at it when I was there; the much more celebrated David garners all the attention.

.....……………………………………………………………………

I started Benvenuto Cellini's autobiography about a week before my trip to Florence, hoping to get a flavor of the Renaissance city from a contemporary account. Cellini was born in Florence in 1500 so his life spanned three-quarters of the famous century. He tells us that he was apprenticed to a goldsmith at a young age and that he worked on commissions for many powerful people. His early work was carried out mainly for the Medici family in Florence, but after a dispute in which he killed a man, he was obliged to flee the city. He wasn't yet twenty.

After that unfortunate episode, Cellini set out for Rome where he worked for the Medici pope, Leo X, and for Leo's successor and cousin, Giulio de' Medici, who became pope in 1523 and who commissioned Michaelangelo to paint 'The Last Judgement' in the Sistine Chapel around the same time.

As well as setting jewels and minting coins for the pope, Cellini served as a soldier during the Sack of Rome in 1527 and later spent time as a prisoner in the Castel Sant'Angelo for knifing a man in a dispute; he'd made many enemies in Rome by then. He escaped from the Castello in a dramatic escapade which involved knotted bedsheets and a broken leg, and took refuge in France in the court of François I. The French King had welcomed Leonardo da Vinci some years before when he too had run out of friends in Italy. Cellini spent quite a few years in France in the King's service, working on small decorative objects in gold and silver such as tableware, jewelry, and commemorative coins and medals.

..........……………………………………………………………

By the time I reached Florence, I was two thirds of the way through Benvenuto Cellini's excellent account of his life, and though I enjoyed reading about his adventures, I despaired of him ever returning to his native city. I half wished I'd chosen a book about someone who'd spent more of his life in the Tuscan capital, and was glad I'd taken Forster's book along since it, at least, was set in Florence.

Cellini was forty-five at this point in his tumultuous career, and was making as many enemies in France as he'd made in Italy. He had also fallen out with the King over the terms of his contract so, much to my relief, he turned his horse in the direction of Italy hoping to regain the patronage of his first employers, the Florentine Medicis.

Benvenuto and I were now finally in the same place.

Cellini's return to his native city reawakened his early but as yet unrealized ambition: he'd worked as a goldsmith most of his life but he longed to produce a work on a larger scale so when Duke Pier Luigi de' Medici asked about his projects, Cellini answered that he "would willingly make a great statue in marble or bronze for his fine piazza." The Duke decided that he would like a statue of Perseus, in bronze.

I read that passage the evening after I arrived in Florence, and the very day I'd seen the Perseus statue in the Piazza Della Signoria for the first time. There is no plaque on the statue, nothing to indicate who created it, so discovering that the statue that had entranced me was by Cellini was a truly extraordinary moment. Reading has few greater pleasures.

While I'd expected to see small objects by Cellini in gold and silver in the museum, I'd never expected him to have produced a statue in bronze. The description of the casting of the Perseus is by far the most interesting chapter in the autobiography - I'd recommend this book for that section alone. One of the challenges was heating the alloy sufficiently so that it would flow all the way along the upraised arm of the mould and into the severed head. The parallels between the blood pouring from the Medusa's head and the liquid alloy are hard to ignore - the streams of blood would have been the most difficult area for the molten bronze to reach. But Cellini was always motivated by challenges and used all his ingenuity to overcome such difficulties.

view image:

Spoiler

However, the newly minted sculptor wasn't satisfied with a commission for a work in bronze; he longed to work in marble. From then on, he put himself forward for any of the Medici commissions involving marble; he was determined to compete with the major Florentine sculptors of the day, Bartolomeo Ammanato and Baccio Bandinelli. When the Duke was planning the enormous Neptune for the fountain in the Piazza della Signoria, the exact location of Forster's dramatic scene, Cellini submitted a design. The Duke gave the commission to Ammanato.

view image:

Spoiler

However, it was Baccio Bandinelli, who had created the Hercules and Cacus sculpture on the Piazza in 1535, who became Cellini's greatest rival during subsequent marble commissions. Cellini rarely praises the work of other artists, with the exception of Michaelangelo Buonarroti, but he is particularly critical of Bandinelli's Hercules, as he tells the Duke:

view image:

Spoiler

'...if you were to shave off Hercules's hair, there wouldn't be any noddle left to hold the brains; and as for his face, one can't tell whether it's a man's or that of some cross between a lion and an ox...moreover, its great hideous shoulders are like nothing so much as two pommels of an ass's pack-saddle; and the breasts and all the muscles are not modelled from a man, but from a great sack of melons.."

view image:

Spoiler

In spite of Cellini's best efforts, Bandinelli retained the Duke's favour but Cellini received three commissions for works in marble after his rival's sudden death: a Narcissus and a Ganymede, both done in the late 1540s, and an Apollo with Hyacinth from 1550. He also made a Christ figure in marble for the Duke's wife.

view image:

Spoiler

Around this time, Cellini turned his attention to investing his earnings and acquiring property; he had fallen out of favor with the Medicis in any case and received no more commissions.

He began writing his autobiography in 1558 and continued until 1565 when he embarked on a Treatise on Goldsmithing and Sculpture. He died in 1571.

......……………………………………………………………………

I crossed the famous Ponte Vecchio which spans the Arno several times during my stay in Florence. It was there that Forster's heroine Lucy was taken to recover from the trauma of seeing so much blood spilled on the Piazza. Today, it's a frantically busy place full of vendors and tourists, the kind of place I tend to hurry through, so it wasn't until the final day of my Florence visit that I noticed the commemorative bust at one end of the bridge.

I stepped closer to see who was represented there: none other than Benvenuto Cellini.

view image:

Spoiler

adventurous

slow-paced

I thought this may be a bit interesting I was Not Ready for this wild ride. So let's get into personality

Benvenuto Cellini (b.1500) was a renaissance florentine goldsmith, sculptor. What the autobiography reveals is that he was also, a shit. it's rare I think, that somebody writing their own account, their autobiography, comes across this awful - he picks fights, endlessly, and nearly always seems in the wrong. he has the biggest ego you can imagine, even if he is remarkably talented. It's SO entertaining. I kept forgetting that this is 'history', that this isn't a hare-brained Count of Monte Cristo parody, three centuries early. now I'm sure that Most of what Cellini is saying in here is lies - I'm good with that. You won't like him. but what a read

Benvenuto Cellini (b.1500) was a renaissance florentine goldsmith, sculptor. What the autobiography reveals is that he was also, a shit. it's rare I think, that somebody writing their own account, their autobiography, comes across this awful - he picks fights, endlessly, and nearly always seems in the wrong. he has the biggest ego you can imagine, even if he is remarkably talented. It's SO entertaining. I kept forgetting that this is 'history', that this isn't a hare-brained Count of Monte Cristo parody, three centuries early. now I'm sure that Most of what Cellini is saying in here is lies - I'm good with that. You won't like him. but what a read

adventurous

funny

informative

lighthearted

fast-paced

Honestly maybe the best autobiography I've ever read. Short chapters make it easily digestible, the writing style (and translations) are excellent. I came off this after reading Ascanio, by Dumas, and finding out that Cellini was a real guy. And it's evident that Dumas had read this book, because there are things, almost word for word, taken from here. I'll be buying a physical copy, for sure.

adventurous

dark

medium-paced

adventurous

challenging

informative

inspiring

tense

fast-paced

I haven't read much autobiographies of designers, but strongly suspect that this one is one of the best available. Lots of inside info on how successful studios work internally and externally, about the sales pipelines and so forth. Also, not many designers are open enough to tell the world how they killed people!