You need to sign in or sign up before continuing.

Take a photo of a barcode or cover

Well, I've only gotten 5% into this book and I came to Netgalley to read other members' reviews in order to see if it was actually worth continuing or not, so it's safe to say that the beginning of the novel isn't particularly captivating. Anyway I've seen from another member's review that the girl who is struggling with her sexuality (who hasn't been introduced to me yet) goes on a date with a boy at the end of the novel, so I think I'll leave it here and not set myself up for disappointment if that's true.

The main reason I'm giving up after only 5% is that the characters don't seem believable or interesting. Also, this novel has confirmed that I hate it when male writers write female characters. The amount of references to Belinda's boobs is ridiculous in only the first 5%:

'She brought her ankles together, fixed her head-tie and straightened her dress so that it was less bunched around her breasts.'

'She yanked at a hair sprouting from her left, darker nipple, pulling it through bubbles. The root gathered into a frightened peak. She liked the sensation.'

'Belinda squeezed the remaining cedis into her bra, giving herself an uncomfortable, monstrous breast. The high-heels Aunty and Nana said made her feet ‘feminine’ pinched her toes and were more painful than stomach cramps.'

Lol what?

And this random description of two random women:

'They stood behind three nurses who had powerful bottoms and who passed the time by...'

Get ready for these nurses never to be mentioned again.

Not to mention our introduction to Mary is this weird scene where she talks about watching Belinda in the shower all the time, and grabs her breasts (I assume that's what happened):

'Mary shot up from beneath the covers and launched herself at Belinda’s chest. Belinda pushed her off and Mary lost her balance, fell onto the bed. ‘What is this? Are you a –? Are you a stupid –’ Belinda lifted the towel higher. ‘Grabbing for whatever you want, eh?’‘What you worried for?’ Mary arched an eyebrow. ‘I have seen all before. Nothing to be ashamed for. And we both knowing there is gap beneath shower door and I’m never pretending to be quiet about my watchings neither.' (Formatting is a result of directly copying from the advance copy and doesn't reflect the published novel)

Honestly I can't be bothered to find out how the author decides to write about queer female sexuality after the above passages.

Edit: I found out Donkor is actually gay and now I'm even more bewildered about the above quotes!

Thanks to Netgalley and HarperCollins for an advance copy in exchange for an unbiased review.

The main reason I'm giving up after only 5% is that the characters don't seem believable or interesting. Also, this novel has confirmed that I hate it when male writers write female characters. The amount of references to Belinda's boobs is ridiculous in only the first 5%:

'She brought her ankles together, fixed her head-tie and straightened her dress so that it was less bunched around her breasts.'

'She yanked at a hair sprouting from her left, darker nipple, pulling it through bubbles. The root gathered into a frightened peak. She liked the sensation.'

'Belinda squeezed the remaining cedis into her bra, giving herself an uncomfortable, monstrous breast. The high-heels Aunty and Nana said made her feet ‘feminine’ pinched her toes and were more painful than stomach cramps.'

Lol what?

And this random description of two random women:

'They stood behind three nurses who had powerful bottoms and who passed the time by...'

Get ready for these nurses never to be mentioned again.

Not to mention our introduction to Mary is this weird scene where she talks about watching Belinda in the shower all the time, and grabs her breasts (I assume that's what happened):

'Mary shot up from beneath the covers and launched herself at Belinda’s chest. Belinda pushed her off and Mary lost her balance, fell onto the bed. ‘What is this? Are you a –? Are you a stupid –’ Belinda lifted the towel higher. ‘Grabbing for whatever you want, eh?’‘What you worried for?’ Mary arched an eyebrow. ‘I have seen all before. Nothing to be ashamed for. And we both knowing there is gap beneath shower door and I’m never pretending to be quiet about my watchings neither.' (Formatting is a result of directly copying from the advance copy and doesn't reflect the published novel)

Honestly I can't be bothered to find out how the author decides to write about queer female sexuality after the above passages.

Edit: I found out Donkor is actually gay and now I'm even more bewildered about the above quotes!

Thanks to Netgalley and HarperCollins for an advance copy in exchange for an unbiased review.

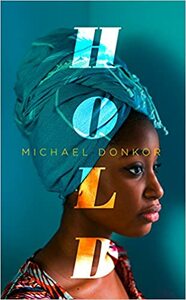

Hold, later renamed as Housegirl, is a ‘coming of age’ novel of a girl, Bellinda who struggles between two world- Ghana and London. She is the ideal housemaid, knows her duties and performs them with perfection. Bellinda finds a sister in Mary- an 11-year-old who still can’t abide by rules.

But soon Bellinda is sent to London as a companion and friend to Amma. Bellinda misses Mary but her only hope at a decent life is to befriend Anna. As these two women start to unfold, a friendship develops between them and they realize that they need each other more than they thought, especially with their inner demons trying to gnaw them away.

The story is slow and is difficult to follow. I finally started to know what was going on after 25% of the story. I liked the characters, their diversity in class and well as opinions. The language, especially the ones with Ghanian dialect slowed me down a lot, and honestly, I found it unnecessary and somewhat annoying.

Overall, I liked the plot as it explored the friendship between teenagers and their struggles.

But soon Bellinda is sent to London as a companion and friend to Amma. Bellinda misses Mary but her only hope at a decent life is to befriend Anna. As these two women start to unfold, a friendship develops between them and they realize that they need each other more than they thought, especially with their inner demons trying to gnaw them away.

The story is slow and is difficult to follow. I finally started to know what was going on after 25% of the story. I liked the characters, their diversity in class and well as opinions. The language, especially the ones with Ghanian dialect slowed me down a lot, and honestly, I found it unnecessary and somewhat annoying.

Overall, I liked the plot as it explored the friendship between teenagers and their struggles.

I listened to this on audio, and parts of it were kind of messy and hard to follow. But, I think this story had so much heart. The friendship between Belinda and Amma was really beautiful to read about (apart from one thing, which gets sort-of resolved later on), as was that between Belinda and Mary. It was so nice to read about such different female characters creating lasting bonds.

Shortlisted for the 2019 Desmond Elliot Prize for debut fiction and longlisted for the Dylan Thomas Prize for young writers

The two of them – Amma, Mary – in their own, very different ways , in their different times and places, had made Belinda think and laugh so hard.

Michael Donkor's excellent debut novel Hold is set in Ghana and South-East London. It opens in December 2002 with 17 year-old Belinda grieving at a traditional funeral in Ghana, but then travels back 9 months to find Belinda working, for the previous 6 months, as a house-girl in Daban, Kumsai, for a wealthy couple, who she knows as Aunty and Uncle, albeit not actual relations.

She was sent away from her home village by her mother, who she no longer has any contact with:

That evening, as Mother had given out her clear instructions about never turning back, perhaps it had been hard to speak so thunderously when, really, under all of that pretending, Mother’s feelings were more unsure and broken.

Although otherwise she seems happy and secure in Daban, and becomes like an elder sister to the other house-girl, 11 year-old Mary. But then a relative of Aunty's arrives from UK, 'Nana', wife of a successful ex-pat businessman Doctor Otuo, and tells Belinda of her own 17 year old daughter, Amma.

'She is very beautiful girl and the book-smartest you will ever find in the UK. Ewurade! Collecting only gold stars and speaking of all these clever ideas I haven’t the foggiest. They even put her in South London Gazette once because of her brains!’ Nana shook her head in disbelief. ‘And when she has a break from doing her homeworks or doing paintings, we shop together in H& M and have nice chats. And she makes her father very proud so he doesn’t even mind that he lacks a son and he never moans of how dear the private school fees are for his bank balance.’

Belinda took the napkin and folded it into quarters. ‘Daznice,’she said. ‘Sounds very nice for you.’

'It used to be nice.’ Nana sighed, put down her Gulder. ‘Past. We have to use past tense because is now lost and gone, you get me? As if in the blinking of a cloud of some smoke she has just become possessed. Not talking. Grumpy. Using just one word, two words for communication. As if she is carrying all of the world on her shoulders.'

Nana and Aunty have decided, before consulting her, on a plan for Belinda - to send her to the UK to live with the Otuo's, not as a housegirl but simply to try and befriend Amma. Belinda's incentive is that the Otuo's will also send money to her mother, since the latter's earnings from her bar job back in the village are inadequate.

But when she has to break the news to Mary, the conversation doesn't go well, Mary feeling that she is being abandoned:

‘You seem to do a very good job of not speaking on the tro tro, me boa?’

‘Not really.’

‘Wo se sɛn?’

‘In my head I had very long talk with you. Very long.’

‘Sa?’ Belinda scooped the contents of the asanka into the frying pan and took a big step back while the oil hissed.

The Otuo's live in a vividly drawn South-East London, which proves rather a disappointment to Belinda. Indeed Donkor cleverly hasn't set this up as a contrast between rich London and poor Ghana, if anything the opposite - even their house is rather small compared to Aunty and Uncle's compound:

Didn’t Nana and Doctor Otuo feel boxed in or too small here? Why did the cars pass right in front of the house – where was the perimeter wall? The swimming pool?

...

The Otuos’ Narbonne Avenue was smart, marked by pointy black lampposts like those outside the Huxtables’ on The Cosby Show repeats Aunty loved. Each morning from her new window, Belinda saw men swinging briefcases and women flicking scarves called pashminas.

But late the following Saturday afternoon, as Nana, Belinda and Amma walked from the house in matching wrappers, a few minutes away on Railton Road, they were somewhere unrecognisable. Clusters of tired buildings were interrupted by a betting shop, an ‘off licence’, the Jamaican Take Away, ‘Chick ‘n’Grillz’. And none of them sold what they promised. Fronts were smashed or boarded up. Even the earlier rain seemed to have collected more dangerously here, lapping at Nana’s peep-toes. A gust came at Belinda with a rumour of nearby bins, beer, and spoiled fruit.

The reader soon realises that Amma's situation is more than just teenage angst:

It had been ages since the Saturday when she had put away all the important things from the Brunswick Manor Gifted and Talented Residential into the trinket box. On that day, it had rained appropriately and persistently . Amma had waited for weeks and weeks to hear anything, anything at all.

On the course, she met a girl Roisin and started a brief lesbian relationship.

Amma was frightened by the wringing knowledge that she could never tell anyone about her body’s response. Because Amma knew the unwieldy truth: no one likes a black girl who likes girls . Friends would wriggle: their liberalism tested by something they couldn’t quite get on board with. Mum would die. Ghanafoɔ would explode in a shower of Jollof.

But to add to her anguish Roisin is no longer returning her calls.

Amma attends an outstanding and prestigious private school SGHS, which one rather suspects draws on St Paul's Girl School (SPGS) where the author himself teaches, albeit he has relocated the school from Hammersmith to Streatham and imposed a school uniform.

And Donkor does indeed skewer the speech patterns and behaviour of Amma and her friends:

Yesterday had been AS Results Day: Amma and all the other prefects had been garlanded with As. Clutching certificates they did a show of being surprised, relieved.

Going home after the results was not an option. Party! Max from Alleyn’s! With his fat house near Dulwich Village? Off they went.

Max’s dad laid boxes of wine and buckets of beers on the long dining table before high-fiving his son on his way out. As soon as the door shut, before anyone could protest, Amma swiped the Beaujolais. She ran to the basement, slipped off her Converse and stationed herself in the corner of their library to hide. Until the Addie Lees and faggy final kisses at 5 or 6 a.m., Max’s front room would sweatily ripple with skaters in children’s jewellery, students from Camberwell doing Art Foundations, adjusting dungarees and wearing tiny hats, and the chavvier girls in jeans revealing a tasty inch of arse crack; the Stella-ed up young Tories, thick of lip, expansive of forehead and primed for showy debate. On the edges of the dancing and grinding, over fuzzy Drum’n’Bass, conversation would offer nothing of importance or comfort.

[...]

When have you been most scared?’ Amma asked Helena.

‘Funny question.’

‘Try. Go on.’

‘What do you need to know for?’

‘Why so reluctant, ma chérie?’

Helena’s pinking eyes flashed. ‘When I thought I might drown. But you know about that. So you’re probably after something –’

‘Doesn’t matter. Keep going.’

‘So, OK, I was about eight or something. Mum was going out with that creepy cellist then.’

‘Eugh, yeah. With the teeth and the fingernails.’

‘The three of us were in Cornwall. He’d never been and Mum was, like, too happs about showing him everything and blah blah.'

He even throws in some self-satire of an A-level English teacher at the school:

‘So, folks, why might Faulks have used this narrative technique in the extract we’re analysing? Can we all remember what we mean by the term “narrative technique”? Who can remember?’

To emphasise ideas in desperate need of razzmatazz or to lend important questions greater jeopardy, the little man at the front of the class stretched his hands out, up, to the side. Mr Stevens – although ‘Titch’ was more informative – sat on the edge of his table, kicking his legs like a child on a swing. Each of the fifteen girls under his tutelage were destined for As and Russell Group universities, regardless of his efforts. The prospect, the certainty of success, dispirited Amma.

....

Getting an A for an essay was pleasingly straightforward. There were rules to be followed, well-selected places in paragraphs where untaught flair was required. Hiding her feelings in order to turn into the kind of daughter Nana Otuo wanted presented a greater challenge.

SHGS contrasts to the community school that Belinda attends, at the Otuo's insistence, to study a GCSE in English literature.

A rather lazy comparison would be that Donkor does for the multi-ethnic communities of SE London what Zadie Smith has done for the North-West. The book itself makes a nod in that direction, with Belinda's book shelves soon containing:

Penguin copies of Macbeth, Romeo and Juliet, The Tempest and Lord of the Flies for Abacus. A Lambeth Borough Library Card that Mrs Al-Kawthari had helped her apply for. Things Fall Apart and [b:White Teeth|3711|White Teeth|Zadie Smith|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1374739885l/3711._SY75_.jpg|7480] for fun.

And Macbeth is a key reference, which she studies at the community school:

Belinda remembered what Macbeth says when he hears about his Lady’s death: how life is only a walking shadow. She had liked the line very much. Mrs Al-Kawthari had put it up on the OHP and asked for volunteers to talk about it. Robert had said it was about God and the riches awaiting us in Heaven. Belinda had not been afraid to only say she found the sentence complicated, beautiful and true.

with Belinda's excessive cleaning, to the Otuo's disapproval given that she is not there to work, reminiscent of Lady Macbeth.

She was pleased at the muck in its bristles. She got to her feet and turned the hot tap on. With ungloved hands, under the stream of scalding water, she plucked the dirt from those spines until they were as white as she could manage.

The reason for this is buried in her past but gradually becomes clear to the reader, as she thinks back to the day she left her mother.Maybe the following day, after the driver had taken Belinda away, when Mother was doing her sticky nastiness with some evil man, Mother might have stared up at the dead insects on the ceiling and not fully felt the pressure of the heaving body on top of her because the scale of what she had lost and the emptiness of what lay ahead filled every space in her mind.

As the girls gradually open up to each other, Belinda's initial reaction to Amma's secret is far from accepting and Amma fails initially to see why Belinda is so traumatised. But after the tragedy leading to the funeral than opens the book forces Belinda back to Ghana, the two girls have more time to think on the other's situation and their own.

This isn't a novel offering easy closure and all the better for that. If there is a redemptive message from the book it is that ultimately one will be able to cope even with what seem like impossible burdens. Amma slips into a Katherine Mansfield book she lends Belinda for the flight the poem Michiko Dead by Jack Gilbert, from which the novel takes its title:

He manages like somebody carrying a box

that is too heavy, first with his arms

underneath. When their strength gives out,

he moves the hands forward, hooking them

on the corners, pulling the weight against

his chest. He moves his thumbs slightly

when the fingers begin to tire, and it makes

different muscles take over.

Afterward, he carries it on his shoulder, until the blood

drains out of the arm that is stretched up

to steady the box and the arm goes numb. But now

the man can hold underneath again, so that

he can go on without ever putting the box down.

Overall, a beautifully written and powerful novel - recommended.

The two of them – Amma, Mary – in their own, very different ways , in their different times and places, had made Belinda think and laugh so hard.

Michael Donkor's excellent debut novel Hold is set in Ghana and South-East London. It opens in December 2002 with 17 year-old Belinda grieving at a traditional funeral in Ghana, but then travels back 9 months to find Belinda working, for the previous 6 months, as a house-girl in Daban, Kumsai, for a wealthy couple, who she knows as Aunty and Uncle, albeit not actual relations.

She was sent away from her home village by her mother, who she no longer has any contact with:

That evening, as Mother had given out her clear instructions about never turning back, perhaps it had been hard to speak so thunderously when, really, under all of that pretending, Mother’s feelings were more unsure and broken.

Although otherwise she seems happy and secure in Daban, and becomes like an elder sister to the other house-girl, 11 year-old Mary. But then a relative of Aunty's arrives from UK, 'Nana', wife of a successful ex-pat businessman Doctor Otuo, and tells Belinda of her own 17 year old daughter, Amma.

'She is very beautiful girl and the book-smartest you will ever find in the UK. Ewurade! Collecting only gold stars and speaking of all these clever ideas I haven’t the foggiest. They even put her in South London Gazette once because of her brains!’ Nana shook her head in disbelief. ‘And when she has a break from doing her homeworks or doing paintings, we shop together in H& M and have nice chats. And she makes her father very proud so he doesn’t even mind that he lacks a son and he never moans of how dear the private school fees are for his bank balance.’

Belinda took the napkin and folded it into quarters. ‘Daznice,’she said. ‘Sounds very nice for you.’

'It used to be nice.’ Nana sighed, put down her Gulder. ‘Past. We have to use past tense because is now lost and gone, you get me? As if in the blinking of a cloud of some smoke she has just become possessed. Not talking. Grumpy. Using just one word, two words for communication. As if she is carrying all of the world on her shoulders.'

Nana and Aunty have decided, before consulting her, on a plan for Belinda - to send her to the UK to live with the Otuo's, not as a housegirl but simply to try and befriend Amma. Belinda's incentive is that the Otuo's will also send money to her mother, since the latter's earnings from her bar job back in the village are inadequate.

But when she has to break the news to Mary, the conversation doesn't go well, Mary feeling that she is being abandoned:

‘You seem to do a very good job of not speaking on the tro tro, me boa?’

‘Not really.’

‘Wo se sɛn?’

‘In my head I had very long talk with you. Very long.’

‘Sa?’ Belinda scooped the contents of the asanka into the frying pan and took a big step back while the oil hissed.

The Otuo's live in a vividly drawn South-East London, which proves rather a disappointment to Belinda. Indeed Donkor cleverly hasn't set this up as a contrast between rich London and poor Ghana, if anything the opposite - even their house is rather small compared to Aunty and Uncle's compound:

Didn’t Nana and Doctor Otuo feel boxed in or too small here? Why did the cars pass right in front of the house – where was the perimeter wall? The swimming pool?

...

The Otuos’ Narbonne Avenue was smart, marked by pointy black lampposts like those outside the Huxtables’ on The Cosby Show repeats Aunty loved. Each morning from her new window, Belinda saw men swinging briefcases and women flicking scarves called pashminas.

But late the following Saturday afternoon, as Nana, Belinda and Amma walked from the house in matching wrappers, a few minutes away on Railton Road, they were somewhere unrecognisable. Clusters of tired buildings were interrupted by a betting shop, an ‘off licence’, the Jamaican Take Away, ‘Chick ‘n’Grillz’. And none of them sold what they promised. Fronts were smashed or boarded up. Even the earlier rain seemed to have collected more dangerously here, lapping at Nana’s peep-toes. A gust came at Belinda with a rumour of nearby bins, beer, and spoiled fruit.

The reader soon realises that Amma's situation is more than just teenage angst:

It had been ages since the Saturday when she had put away all the important things from the Brunswick Manor Gifted and Talented Residential into the trinket box. On that day, it had rained appropriately and persistently . Amma had waited for weeks and weeks to hear anything, anything at all.

Amma was frightened by the wringing knowledge that she could never tell anyone about her body’s response. Because Amma knew the unwieldy truth: no one likes a black girl who likes girls . Friends would wriggle: their liberalism tested by something they couldn’t quite get on board with. Mum would die. Ghanafoɔ would explode in a shower of Jollof.

But to add to her anguish Roisin is no longer returning her calls.

Amma attends an outstanding and prestigious private school SGHS, which one rather suspects draws on St Paul's Girl School (SPGS) where the author himself teaches, albeit he has relocated the school from Hammersmith to Streatham and imposed a school uniform.

Donkor’s day job as an English teacher also helped him access the female teenage mindset. His current post is at St Paul’s girls’ school in west London. “It’s funny,” he says, “because the girls at school ask me whether they have inspired some of my observations about teenage girls… and yeah, I’m watchful of the ways young people interact. And how direct they are.”(https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/jan/14/debut-novelists-2018-donkor-halliday-gowar-bracht-kitson-libby-page-aj-pearce)

And Donkor does indeed skewer the speech patterns and behaviour of Amma and her friends:

Yesterday had been AS Results Day: Amma and all the other prefects had been garlanded with As. Clutching certificates they did a show of being surprised, relieved.

Going home after the results was not an option. Party! Max from Alleyn’s! With his fat house near Dulwich Village? Off they went.

Max’s dad laid boxes of wine and buckets of beers on the long dining table before high-fiving his son on his way out. As soon as the door shut, before anyone could protest, Amma swiped the Beaujolais. She ran to the basement, slipped off her Converse and stationed herself in the corner of their library to hide. Until the Addie Lees and faggy final kisses at 5 or 6 a.m., Max’s front room would sweatily ripple with skaters in children’s jewellery, students from Camberwell doing Art Foundations, adjusting dungarees and wearing tiny hats, and the chavvier girls in jeans revealing a tasty inch of arse crack; the Stella-ed up young Tories, thick of lip, expansive of forehead and primed for showy debate. On the edges of the dancing and grinding, over fuzzy Drum’n’Bass, conversation would offer nothing of importance or comfort.

[...]

When have you been most scared?’ Amma asked Helena.

‘Funny question.’

‘Try. Go on.’

‘What do you need to know for?’

‘Why so reluctant, ma chérie?’

Helena’s pinking eyes flashed. ‘When I thought I might drown. But you know about that. So you’re probably after something –’

‘Doesn’t matter. Keep going.’

‘So, OK, I was about eight or something. Mum was going out with that creepy cellist then.’

‘Eugh, yeah. With the teeth and the fingernails.’

‘The three of us were in Cornwall. He’d never been and Mum was, like, too happs about showing him everything and blah blah.'

He even throws in some self-satire of an A-level English teacher at the school:

‘So, folks, why might Faulks have used this narrative technique in the extract we’re analysing? Can we all remember what we mean by the term “narrative technique”? Who can remember?’

To emphasise ideas in desperate need of razzmatazz or to lend important questions greater jeopardy, the little man at the front of the class stretched his hands out, up, to the side. Mr Stevens – although ‘Titch’ was more informative – sat on the edge of his table, kicking his legs like a child on a swing. Each of the fifteen girls under his tutelage were destined for As and Russell Group universities, regardless of his efforts. The prospect, the certainty of success, dispirited Amma.

....

Getting an A for an essay was pleasingly straightforward. There were rules to be followed, well-selected places in paragraphs where untaught flair was required. Hiding her feelings in order to turn into the kind of daughter Nana Otuo wanted presented a greater challenge.

SHGS contrasts to the community school that Belinda attends, at the Otuo's insistence, to study a GCSE in English literature.

A rather lazy comparison would be that Donkor does for the multi-ethnic communities of SE London what Zadie Smith has done for the North-West. The book itself makes a nod in that direction, with Belinda's book shelves soon containing:

Penguin copies of Macbeth, Romeo and Juliet, The Tempest and Lord of the Flies for Abacus. A Lambeth Borough Library Card that Mrs Al-Kawthari had helped her apply for. Things Fall Apart and [b:White Teeth|3711|White Teeth|Zadie Smith|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1374739885l/3711._SY75_.jpg|7480] for fun.

And Macbeth is a key reference, which she studies at the community school:

Belinda remembered what Macbeth says when he hears about his Lady’s death: how life is only a walking shadow. She had liked the line very much. Mrs Al-Kawthari had put it up on the OHP and asked for volunteers to talk about it. Robert had said it was about God and the riches awaiting us in Heaven. Belinda had not been afraid to only say she found the sentence complicated, beautiful and true.

with Belinda's excessive cleaning, to the Otuo's disapproval given that she is not there to work, reminiscent of Lady Macbeth.

She was pleased at the muck in its bristles. She got to her feet and turned the hot tap on. With ungloved hands, under the stream of scalding water, she plucked the dirt from those spines until they were as white as she could manage.

The reason for this is buried in her past but gradually becomes clear to the reader, as she thinks back to the day she left her mother.

As the girls gradually open up to each other, Belinda's initial reaction to Amma's secret is far from accepting and Amma fails initially to see why Belinda is so traumatised. But after the tragedy leading to the funeral than opens the book forces Belinda back to Ghana, the two girls have more time to think on the other's situation and their own.

This isn't a novel offering easy closure and all the better for that. If there is a redemptive message from the book it is that ultimately one will be able to cope even with what seem like impossible burdens. Amma slips into a Katherine Mansfield book she lends Belinda for the flight the poem Michiko Dead by Jack Gilbert, from which the novel takes its title:

He manages like somebody carrying a box

that is too heavy, first with his arms

underneath. When their strength gives out,

he moves the hands forward, hooking them

on the corners, pulling the weight against

his chest. He moves his thumbs slightly

when the fingers begin to tire, and it makes

different muscles take over.

Afterward, he carries it on his shoulder, until the blood

drains out of the arm that is stretched up

to steady the box and the arm goes numb. But now

the man can hold underneath again, so that

he can go on without ever putting the box down.

Overall, a beautifully written and powerful novel - recommended.

Just finished reading this.

This is definitely a don't judge a book by it's cover/ titles.

House girl is more appropriate a title but as I read Hold I'm not sure.

It was an easy read.

It wasn't dramatic and quite pedestrian at times. I'll look forward to see what happens in the author's journey as this was a debut.

This is definitely a don't judge a book by it's cover/ titles.

House girl is more appropriate a title but as I read Hold I'm not sure.

It was an easy read.

It wasn't dramatic and quite pedestrian at times. I'll look forward to see what happens in the author's journey as this was a debut.

The premise of the book is good but the dialogue is hands down one of the worst I’ve ever had the displeasure of reading. It made little sense as a supposed representation of twi and even worse it bled into almost all of the dialogue in the book.

Amma is supposed to be brilliant but cannot string a full sentence together? The same for Mrs. Al-Kawthari.

The non dialogue portions of the book make for a compelling story but this should have been betaed by Ghanaians in Ghana as well as London bred.

I’m not Ghanaian but even I can recognise that this was a poor attempt.

Amma is supposed to be brilliant but cannot string a full sentence together? The same for Mrs. Al-Kawthari.

The non dialogue portions of the book make for a compelling story but this should have been betaed by Ghanaians in Ghana as well as London bred.

I’m not Ghanaian but even I can recognise that this was a poor attempt.

emotional

reflective

medium-paced

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

No

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

No

I enjoyed reading this book. It’s not earth-shattering and there really aren’t any tense highs (or lows), but to be honest, I’m starting to enjoy this kind of book a lot more than the other kind.

I enjoyed the technically similar, but conflicting characters of Belinda and Amma; two young women of a similar age, from (in some ways) the same place with completely different experiences, thoughts and ways of moving through life. I found the development of their friendship and the way they interacted (and initially danced around each other) quite realistic - no doubt a result of Donkor’s experiences as a teacher.

The main complaint I think I have is that I found the writing quite ‘crowded’, for want of a better word, like a lot more was being described as happening, than actually was. At times it felt busier, when really just a short sentence would have sufficed to describe a situation, conversation or movement. I was quite often thrown out of the story trying to simplify what exactly was happening at certain moments.

I was kind of disappointed by what felt like a non-committal ending, which I think gave the characters other than Belinda a disservice- particularly Amma. But for the most part, It was just nice to read a story of two young, black girls (and their family) predominantly from a U.K. (I.e not American) perspective, and that wasn’t explicitly about ‘The Black Experience’, suggesting that it is always only about ‘struggle’ or a singular, fixed thing.

*I received an advance copy of Hold via NetGalley in exchange for an honest and fair review*

I enjoyed the technically similar, but conflicting characters of Belinda and Amma; two young women of a similar age, from (in some ways) the same place with completely different experiences, thoughts and ways of moving through life. I found the development of their friendship and the way they interacted (and initially danced around each other) quite realistic - no doubt a result of Donkor’s experiences as a teacher.

The main complaint I think I have is that I found the writing quite ‘crowded’, for want of a better word, like a lot more was being described as happening, than actually was. At times it felt busier, when really just a short sentence would have sufficed to describe a situation, conversation or movement. I was quite often thrown out of the story trying to simplify what exactly was happening at certain moments.

I was kind of disappointed by what felt like a non-committal ending, which I think gave the characters other than Belinda a disservice- particularly Amma. But for the most part, It was just nice to read a story of two young, black girls (and their family) predominantly from a U.K. (I.e not American) perspective, and that wasn’t explicitly about ‘The Black Experience’, suggesting that it is always only about ‘struggle’ or a singular, fixed thing.

*I received an advance copy of Hold via NetGalley in exchange for an honest and fair review*

Strong concept and interesting initially, but ultimately this fell flat for me. The plot was winding and many of the choices didn't seem to serve a purpose. The characters are all represented somewhat the same, and there's not enough distinction and contrast between characters like Belinda and Amma, who are supposed to be polar opposites. I wanted to love this book, I really did, but I was disappointed.

Thanks to NetGalley and the publisher for the ARC in exchange for my honest review.

Thanks to NetGalley and the publisher for the ARC in exchange for my honest review.

I hate to be a harsh critic but this book just wasn’t for me. I read up to page 250 but couldn’t bear it any longer. The broken English, lack of connection to the characters and pace of the book were the real issues for me