Scan barcode

workingfortheknife's review against another edition

4.0

as an unemployed mid 20s woman with clinical depression this hit too close to home for me LMFAO

inbredlamb's review against another edition

challenging

funny

reflective

slow-paced

- Plot- or character-driven? Character

- Strong character development? No

- Loveable characters? It's complicated

- Diverse cast of characters? Yes

- Flaws of characters a main focus? Yes

3.75

another book from school years that i had to read. sooo long, a little boring in the start, but once you get near the middle of the book — you start FEELING it. my professor gave such an amazing analysis of how Oblomov is a hyperbolic face of conservative (liberal nobles) side and Stoltz is a materialists side of revolutionary Russia. just beautifully shown, great metaphors used from a robe to lilac branch to show that Olga and Oblomov’s love is doomed from the start.

Graphic: Death and Mental illness

eingutesomen's review against another edition

5.0

Kann man auf jeden gut relaten

Ende bisschen enttäuschend

Ende bisschen enttäuschend

lizardking_no1's review against another edition

funny

reflective

medium-paced

- Plot- or character-driven? Character

- Strong character development? Yes

- Loveable characters? It's complicated

- Diverse cast of characters? It's complicated

- Flaws of characters a main focus? Yes

4.75

yasin_alm's review against another edition

Oblomovluk nedir iyi anlamak gerek. Bir kısmı zerrece bir iş yapmama hissi

Alıntılar:

"Bütün gece çalışacak! Hiç uyumayacak! Herhalde yılda en az beş bin ruble kazanır. Fena para değil; ama yazı yaz mak, boşuna kafamızı, ruhumuzu harcamak, hayallerimizi, düşüncelerimizi satmak, tabiatımızı zorlamak, durup dinlen- meden hareket içinde olmak, hep bir amaç peşinde koş- mak... Sonra da yazmak, yazmak, dönen bir tekerlek gibi, bir makine gibi yazmak! Yarın, öbür gün, daha öbür gün hep yazmak! Tatil yok! Bayram yok! Ne zaman duracak, ne zaman dinlenecek bu adam? Vah zavallı!"

Alıntılar:

"Bütün gece çalışacak! Hiç uyumayacak! Herhalde yılda en az beş bin ruble kazanır. Fena para değil; ama yazı yaz mak, boşuna kafamızı, ruhumuzu harcamak, hayallerimizi, düşüncelerimizi satmak, tabiatımızı zorlamak, durup dinlen- meden hareket içinde olmak, hep bir amaç peşinde koş- mak... Sonra da yazmak, yazmak, dönen bir tekerlek gibi, bir makine gibi yazmak! Yarın, öbür gün, daha öbür gün hep yazmak! Tatil yok! Bayram yok! Ne zaman duracak, ne zaman dinlenecek bu adam? Vah zavallı!"

teresatumminello's review against another edition

3.0

I probably shouldn’t review this or rate it, as I realized too late I read an abridged edition. (I’m allergic to those.) So my rating is for the public-domain edition only, the earliest translated-into-English version.

In the beginning, with all the comings-and-goings in one room (the setting of which reminded me of [b:A Journey Round My Room|10859817|A Journey Round My Room|Xavier de Maistre|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1355072205s/10859817.jpg|319321]), the first chapters felt like a play—a Beckettian play, due to the absurd conversations and Oblomov’s futile attempts to put on his slippers, much less get up from a reclining position. Later, due to the research of a reading friend (thanks, Reem!), I was told that Beckett had indeed read this novel and likely was influenced by it.

Also of interest to me was Oblomov falling into a high fever at the end of one section: a familiar 19th-century device, but one that almost always befalls a female character. Nothing much came of the incident, but maybe it did in the unabridged version. (Probably not.)

Oblomov’s background is told through dream-sequences, his pampered childhood explaining why he is as he is; though, at least with this edition, I didn’t get enough on the background of his beloved friend and foil, Andrei. All in all, a pleasant enough reading experience, but I’m sure much better in its entirety.

In the beginning, with all the comings-and-goings in one room (the setting of which reminded me of [b:A Journey Round My Room|10859817|A Journey Round My Room|Xavier de Maistre|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1355072205s/10859817.jpg|319321]), the first chapters felt like a play—a Beckettian play, due to the absurd conversations and Oblomov’s futile attempts to put on his slippers, much less get up from a reclining position. Later, due to the research of a reading friend (thanks, Reem!), I was told that Beckett had indeed read this novel and likely was influenced by it.

Also of interest to me was Oblomov falling into a high fever at the end of one section: a familiar 19th-century device, but one that almost always befalls a female character. Nothing much came of the incident, but maybe it did in the unabridged version. (Probably not.)

Oblomov’s background is told through dream-sequences, his pampered childhood explaining why he is as he is; though, at least with this edition, I didn’t get enough on the background of his beloved friend and foil, Andrei. All in all, a pleasant enough reading experience, but I’m sure much better in its entirety.

sense_of_history's review against another edition

See the review in my general account on Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/5592716863

ilse's review against another edition

5.0

It was the moment of solemn stillness in nature, when the creative mind works more actively, poetic thoughts glow more fervently, the heart burns with passion more ardently or suffers more bitter anguish, when the seed of a criminal design ripens unhindered in a cruel soul, when….everhtying in Oblomovka is peacefully and soundly asleep.

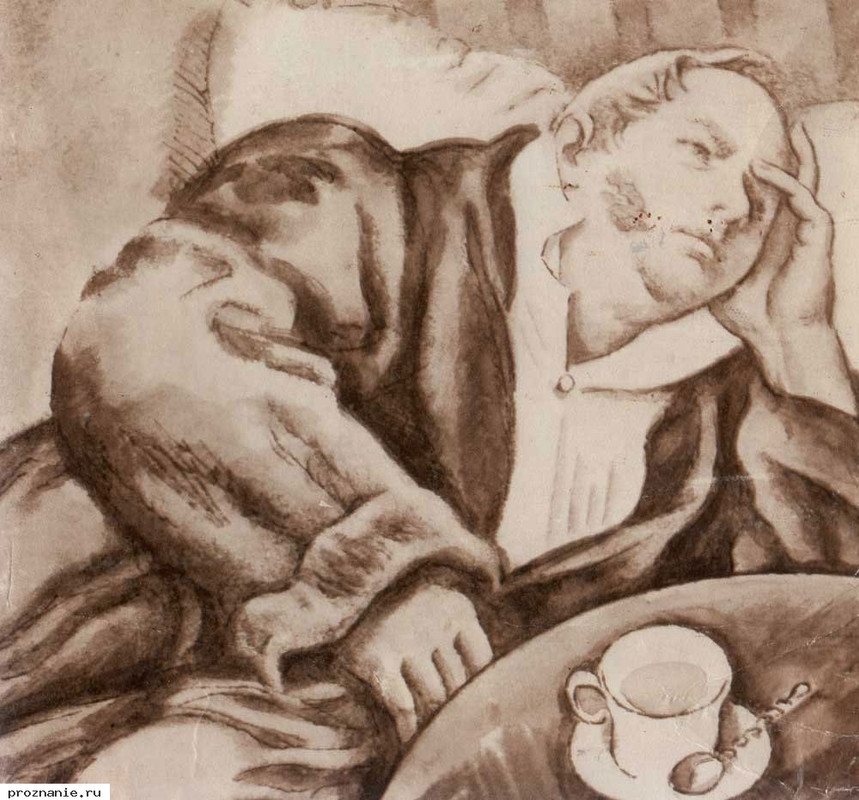

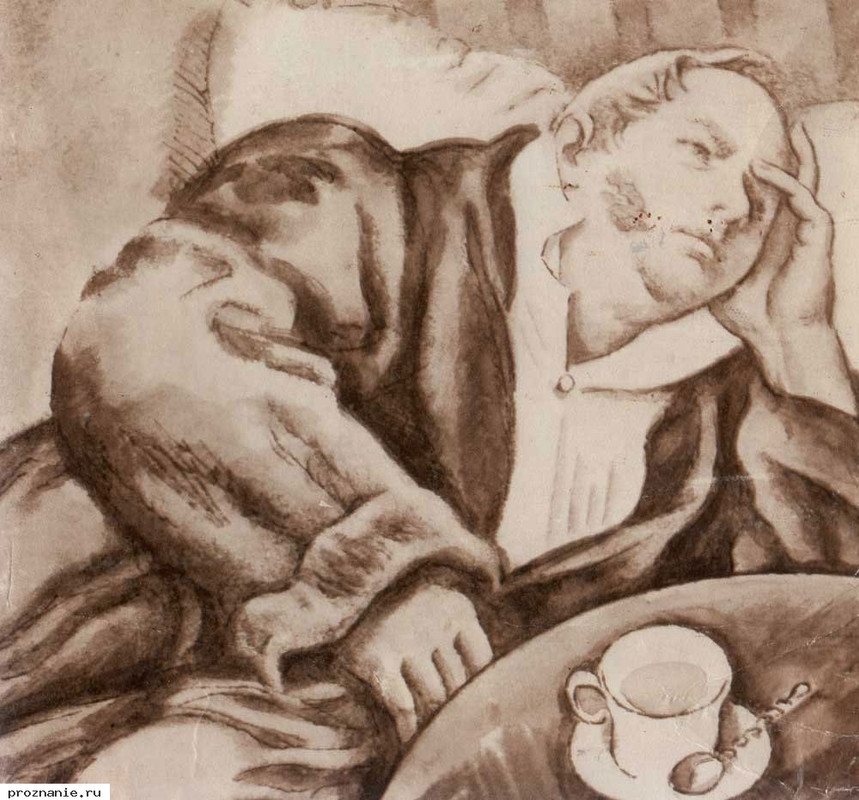

The hero of this delightful 19th-century Russian masterpiece is the melancholy and slothful landowner Ilya Ilyitch Oblomov, who spends about half of the book in bed. Daydreaming about his childhood on Oblomovka, the family estate, he forges grand plans, more hindered than helped by his grumpy servant Zahar. When the adorable Olga appears on stage, singing Casta Diva, Oblomov's listless, lethargic life is turned upside down...

Heartwarming, moving, often funny and so recognizable. After all, isn’t there a little of Oblomov in all of us?

(Illustration N. Shcheglov)

Dit is het uur, waarin de weidse stilte van de nacht heel de natuur in zich opneemt, waarin de scheppende geest nieuwe kracht ontvangt, de dichtader rijkelijker vloeit, waarin het hart heftiger klopt van hartstocht of pijnlijk ineenkrimpt van een smartelijk begeren, waarin de kiem van de misdaad in het wrede gemoed tot welige bloei komt, en waarin in Oblomowka allen ongestoord slapen.

De held van dit heerlijke 19de-eeuwse meesterwerk is de melancholieke en aartsluie landeigenaar Ilja Oblomow, die zowat de helft van het boek doezelend in bed doorbrengt. Dagdromend over zijn jeugd op Oblomowka, het familielandgoed, smeedt hij grootse plannen, daarbij meer gehinderd dan geholpen door zijn knorrige huisknecht. Als de aanbiddelijke Olga op het toneel verschijnt, wordt Oblomows lusteloze leventje danig overhoop gegooid… Hartverwarmend, ontroerend, vaak grappig en heel herkenbaar, want zijn wij niet allemaal een béétje Oblomow?

The hero of this delightful 19th-century Russian masterpiece is the melancholy and slothful landowner Ilya Ilyitch Oblomov, who spends about half of the book in bed. Daydreaming about his childhood on Oblomovka, the family estate, he forges grand plans, more hindered than helped by his grumpy servant Zahar. When the adorable Olga appears on stage, singing Casta Diva, Oblomov's listless, lethargic life is turned upside down...

Heartwarming, moving, often funny and so recognizable. After all, isn’t there a little of Oblomov in all of us?

(Illustration N. Shcheglov)

Dit is het uur, waarin de weidse stilte van de nacht heel de natuur in zich opneemt, waarin de scheppende geest nieuwe kracht ontvangt, de dichtader rijkelijker vloeit, waarin het hart heftiger klopt van hartstocht of pijnlijk ineenkrimpt van een smartelijk begeren, waarin de kiem van de misdaad in het wrede gemoed tot welige bloei komt, en waarin in Oblomowka allen ongestoord slapen.

De held van dit heerlijke 19de-eeuwse meesterwerk is de melancholieke en aartsluie landeigenaar Ilja Oblomow, die zowat de helft van het boek doezelend in bed doorbrengt. Dagdromend over zijn jeugd op Oblomowka, het familielandgoed, smeedt hij grootse plannen, daarbij meer gehinderd dan geholpen door zijn knorrige huisknecht. Als de aanbiddelijke Olga op het toneel verschijnt, wordt Oblomows lusteloze leventje danig overhoop gegooid… Hartverwarmend, ontroerend, vaak grappig en heel herkenbaar, want zijn wij niet allemaal een béétje Oblomow?

fionnualalirsdottir's review against another edition

My one-book-leads-to-another shelf gets a lot of use. The motivation to read a book I've delayed reading always gets a kickstart when I see it referred to in another book. In this case, the book title wasn't mentioned, just the author's name. Yes, Hervé Le Tellier mentioned Ivan Goncharov in [b:L'Anomalie|53970536|L'Anomalie|Hervé Le Tellier|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1591947943l/53970536._SX50_.jpg|84339980], and as 'Oblomov' had been lying about in my house for years, sometimes by the bed, sometimes on a table beside the sofa, regularly dust-laden and generally the worse for wear, I thought it time to discover what 'Oblomov' was about. Well, it's about a man who lies about on his bed or on his sofa and whose clothes are dust-laden and the worse for wear. What was it Oscar Wilde said about life imitating art?

marc129's review against another edition

4.0

“Oh my gosh! Life just won't leave me alone.”

I debated for a long time whether to give this a 3 or 4 star rating (yes, I know, my rating scale is low) but the further I got from the end of reading this book, the more I became convinced that only 4 stars could do justice to it. No, this is not a perfect novel, it even contains some fundamental weaknesses, but I can't help it, in the end Ilya Ilich Oblomov's tragicomic character captivated me. Even more than Prince Myshkin, Dostoyevsky's Idiot, he managed to convince me of his sincerity, truthfulness, and pure heart. The latter sounds very pathetic, I know, but apparently I have enough sentimental romanticism in me for people like Ilya Ilich to break my heart.

I am not going to analyze this book too much, that has been done so many times, with and without expertise. What particularly charmed me is that our poor Oblomov realizes all too well that he is an aberration, that his inherent lethargy has no place, especially in a society (Russia in the first half of the 19th century) that is undergoing rapid change. I was constantly struck by the passages in which Oblomov laments his fate and says he does not know who he really is, and why he is the way he is.

At the same time, he knows how to pinpoint the new, modern society that is about to dawn, to expose the emptiness of busy, industrious existence: “The perpetual running to and fro, the perpetual play of petty desires, especially greed , people trying to spoil things for others, the tittle-tattle, the gossip, the slights, the way they look you up and down. You listen to what they're talking about and it makes your head spin. It's stupefying... It's tedium. Tedium! Where is the human being in this? Where is his integrity? Where did it go? How did it get exchanged for all this pettiness?”

And I know it all too well: what Oblomov offers as alternative, his permanent inertia, is so unrealistic and even immoral (his friend Stolz rubs it in hard). But at the same time, Oblomov's representation of the ideal life touches me: “After that, I put on a roomy coat or jacket, put my arm around my wife's waist, and she and I take a stroll down the endless, dark allée, walking quietly, thoughtfully, silent or thinking out loud, daydreaming, counting my minutes of happiness like the beating of a pulse, listening to my heart beat and sink, seeking sympathy in nature, and before we know it we come out on a stream and field . The river is lapping a little, ears of grain are waving in the breeze, and it's hot. We get into the boat and my wife steers us, barely lifting her oar.”

Goncharov, through Oblomov, has perfectly succeeded in exposing the splits of modern man: the nervous drive towards constant change and improvement as opposed to the childish yearning for simplicity, security and bliss. 4 stars, well deserved.

PS. I read Maria Schwartz's English translation (2008), based on the 1862 version edited by Gontsharov himself, which is far preferable to the 1859 original.

I debated for a long time whether to give this a 3 or 4 star rating (yes, I know, my rating scale is low) but the further I got from the end of reading this book, the more I became convinced that only 4 stars could do justice to it. No, this is not a perfect novel, it even contains some fundamental weaknesses, but I can't help it, in the end Ilya Ilich Oblomov's tragicomic character captivated me. Even more than Prince Myshkin, Dostoyevsky's Idiot, he managed to convince me of his sincerity, truthfulness, and pure heart. The latter sounds very pathetic, I know, but apparently I have enough sentimental romanticism in me for people like Ilya Ilich to break my heart.

I am not going to analyze this book too much, that has been done so many times, with and without expertise. What particularly charmed me is that our poor Oblomov realizes all too well that he is an aberration, that his inherent lethargy has no place, especially in a society (Russia in the first half of the 19th century) that is undergoing rapid change. I was constantly struck by the passages in which Oblomov laments his fate and says he does not know who he really is, and why he is the way he is.

At the same time, he knows how to pinpoint the new, modern society that is about to dawn, to expose the emptiness of busy, industrious existence: “The perpetual running to and fro, the perpetual play of petty desires, especially greed , people trying to spoil things for others, the tittle-tattle, the gossip, the slights, the way they look you up and down. You listen to what they're talking about and it makes your head spin. It's stupefying... It's tedium. Tedium! Where is the human being in this? Where is his integrity? Where did it go? How did it get exchanged for all this pettiness?”

And I know it all too well: what Oblomov offers as alternative, his permanent inertia, is so unrealistic and even immoral (his friend Stolz rubs it in hard). But at the same time, Oblomov's representation of the ideal life touches me: “After that, I put on a roomy coat or jacket, put my arm around my wife's waist, and she and I take a stroll down the endless, dark allée, walking quietly, thoughtfully, silent or thinking out loud, daydreaming, counting my minutes of happiness like the beating of a pulse, listening to my heart beat and sink, seeking sympathy in nature, and before we know it we come out on a stream and field . The river is lapping a little, ears of grain are waving in the breeze, and it's hot. We get into the boat and my wife steers us, barely lifting her oar.”

Goncharov, through Oblomov, has perfectly succeeded in exposing the splits of modern man: the nervous drive towards constant change and improvement as opposed to the childish yearning for simplicity, security and bliss. 4 stars, well deserved.

PS. I read Maria Schwartz's English translation (2008), based on the 1862 version edited by Gontsharov himself, which is far preferable to the 1859 original.