Take a photo of a barcode or cover

92 reviews for:

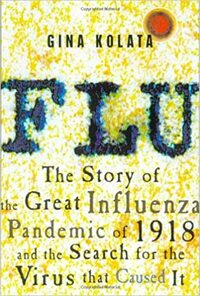

Flu: The Story Of The Great Influenza Pandemic Of 1918 And The Search For The Virus That Caused It

Gina Kolata

92 reviews for:

Flu: The Story Of The Great Influenza Pandemic Of 1918 And The Search For The Virus That Caused It

Gina Kolata

The so called "Spanish flu" pandemic of late 1918/early 1919 is one that has seemingly fallen off the face of the earth. Out of all the American and World History classes I have taken in my life, I can't recall ever studying the 1918 flu. Not in any great detail, at any rate. Which, after having read this book, seems strange considering the massive impact the outbreak had on the entire world.

The number of people killed by the flu - conservative estimates have the number at 20 million, though some experts say the number is as high as 100 million - was staggering. Entire families and in some cases, entire towns, were nearly wiped out by a virus more deadly than anything ever encountered before. There were more fatalities from the 1918 flu than from the Black Death. More soldiers died from the flu than from battle in World War I.

And just as quickly as it began, sweeping through the world's population at an alarming pace, killing people within mere days, it ended. There were subsequent influenza pandemics, but never one as severe. And after the devastation the disease wreaked, it seemed like once it was gone, everyone just wanted to pretend it never happened. No one wanted to talk about it. Out of sight, out of mind.

Only, if it happened once, it could happen again, and a few scientists set out to capture the virus that caused the massively deadly pandemic so they could create a vaccine to stop it in its tracks if it ever reappeared.

Part history book, part mystery story, part science textbook, Flu offers an interesting, at times riveting, story of how modern science techniques can be used to solve a (then) 80-year-old cold case. It's also a tale of hubris and over-caution and personal tragedy. And while I was hoping for a big reveal at the end - the name and details of the deadly virus - I understand that it's never that easy in the real world. And the fact that they were even able to pull fragments of the deadly virus from the frozen lungs of long-dead victims buried in Alaskan permafrost is an amazing feat.

Kolata does a great job of writing a book that balances technical science with poignant history. A very interesting read.

The number of people killed by the flu - conservative estimates have the number at 20 million, though some experts say the number is as high as 100 million - was staggering. Entire families and in some cases, entire towns, were nearly wiped out by a virus more deadly than anything ever encountered before. There were more fatalities from the 1918 flu than from the Black Death. More soldiers died from the flu than from battle in World War I.

And just as quickly as it began, sweeping through the world's population at an alarming pace, killing people within mere days, it ended. There were subsequent influenza pandemics, but never one as severe. And after the devastation the disease wreaked, it seemed like once it was gone, everyone just wanted to pretend it never happened. No one wanted to talk about it. Out of sight, out of mind.

Only, if it happened once, it could happen again, and a few scientists set out to capture the virus that caused the massively deadly pandemic so they could create a vaccine to stop it in its tracks if it ever reappeared.

Part history book, part mystery story, part science textbook, Flu offers an interesting, at times riveting, story of how modern science techniques can be used to solve a (then) 80-year-old cold case. It's also a tale of hubris and over-caution and personal tragedy. And while I was hoping for a big reveal at the end - the name and details of the deadly virus - I understand that it's never that easy in the real world. And the fact that they were even able to pull fragments of the deadly virus from the frozen lungs of long-dead victims buried in Alaskan permafrost is an amazing feat.

Kolata does a great job of writing a book that balances technical science with poignant history. A very interesting read.

This isn’t really the story of the pandemic itself. There’s really only a chapter or two that goes into that. It’s mainly about the scientists trying to figure out what exact type of flu it was. Interesting, but not as interesting as it could have been.

informative

reflective

slow-paced

This was a fascinating look at the 1918 Influenza pandemic, but I always seem to run into the same problem with science books. The well-received and highly rated ones are often older, and by the time I get around to reading them, I wish for a more current look at the same topic. I would love to read about outbreaks we've had since 1999 when this was written, like SARS (which I know is not influenza) and the 2009 H1N1 flu.

Such a badly written book about a horrible and fascinating pandemic. For a much better treatment of pandemics, especially emerging diseases, try The Coming Plague.

I read this right after I read John Barry's The Great Influenza. They are very different books and I'm glad I read both. Barry's book is densely packed with information while this one is a bit lighter. But in terms of the subject matter, she spends a fair amount of time on various digressions, such as the 1976 flu vaccination effort and the discovery of the H5N1 avian flu. Barry's book comprehensively covers the period before and during the 1918 pandemic - a little too comprehensively, perhaps - while Gina Kolata's book does not really begin until 1950ish when the hunt for the virus takes off. Her style as always is easy to read and conversational, but sometimes I suspect she sacrifices accuracy for the sake of a simpler, more entertaining narrative. A good read, but I'm not going around recommending it.

informative

reflective

medium-paced

Too much fluff. I was expecting more history, more stories from the pandemic and more science. Not descriptions of various scientists physical looks or complete backstories. Not what I expected at all.

When the 24-hour news channels developed a morbid fascination with the Ebola virus last summer, I must admit, I did, too. Being an ardent believer in the premise that we best deal with an uncertain future if we better understand our past, I got to digging around and found this fascinating book.

Essentially, Kolata presents you with a highly readable account of the 1918 flu pandemic that killed millions of people worldwide, including millions of American young adults.

I read with horror about death tolls growing at such a rapid rate that people stopped attending funerals of their dead in large cities, piling bodies up outside in some cases for sanitation wagons to take away—and folks, this was in an American city, not some third-world place whose name we can barely pronounce.

If a plague of the same virility struck today, an estimated 1.5 million Americans would die. The flue killed more U.S. soldiers than did all of the battles of World War I. in which they participated.

If you enjoy a good mystery, you’ll like this book, since it focuses on the detective work necessary to find this disease. Indeed, this particular strain was located by scientists at a national military tissue storage facility and in a remote Alaskan cemetery inside the remains of a plus-sized Eskimo woman.

Kolata speculates on what could happen should an airborne killer disease strike again, and her perspective is sobering indeed.

If I have any criticism of this book, it is that it didn’t focus hard enough on the societal changes and impact of the 1918 flu. We had a killer on our hands, and we don’t really know where it started or why it mysteriously ended. Granted, we think that some kind of bird flu virus blended with a disease borne by pigs, and that deadly blend was carried to a human who spread what would become a killer that makes the bubonic plague rather inconsequential by comparison.

There is some science in here—you can’t have a book like this and not touch on the science of germ creation, cell penetration, etc., and of course, the stories of the competing scientists who wanted to find the virus are both interesting and unsettling.

Essentially, Kolata presents you with a highly readable account of the 1918 flu pandemic that killed millions of people worldwide, including millions of American young adults.

I read with horror about death tolls growing at such a rapid rate that people stopped attending funerals of their dead in large cities, piling bodies up outside in some cases for sanitation wagons to take away—and folks, this was in an American city, not some third-world place whose name we can barely pronounce.

If a plague of the same virility struck today, an estimated 1.5 million Americans would die. The flue killed more U.S. soldiers than did all of the battles of World War I. in which they participated.

If you enjoy a good mystery, you’ll like this book, since it focuses on the detective work necessary to find this disease. Indeed, this particular strain was located by scientists at a national military tissue storage facility and in a remote Alaskan cemetery inside the remains of a plus-sized Eskimo woman.

Kolata speculates on what could happen should an airborne killer disease strike again, and her perspective is sobering indeed.

If I have any criticism of this book, it is that it didn’t focus hard enough on the societal changes and impact of the 1918 flu. We had a killer on our hands, and we don’t really know where it started or why it mysteriously ended. Granted, we think that some kind of bird flu virus blended with a disease borne by pigs, and that deadly blend was carried to a human who spread what would become a killer that makes the bubonic plague rather inconsequential by comparison.

There is some science in here—you can’t have a book like this and not touch on the science of germ creation, cell penetration, etc., and of course, the stories of the competing scientists who wanted to find the virus are both interesting and unsettling.