You need to sign in or sign up before continuing.

Take a photo of a barcode or cover

A challenging read with all the 15th century style of writing. Expect plenty of flipping between the prose and reference notes, but nice bit of fiction with highly descriptive elements.

There is no denying this is a staggering work that has stood the test of time, so my review and rating is more on how I enjoyed it in comparison to other great works. ,A four star on this is not the same as a four star on the latest romance novel, obviously.

For me, I enjoyed Inferno and Paradise -- the latter which shocked me, because even the additional materials said that Paradise was the most difficult to get behind and "modern readers" wouldn't appreciate it. Inferno was fascinating to see the punishments, and the descriptions and language used is fascinating. BY the time I'd reached Purgatory, though, I was less enthused, and there was the fatigue of "how many more times is Dante going to be shy about asking a question, spend 30 lines writing about it, only to be told they already know what question he will ask" or "how many more times is he going to tell me how hard it is to write this" or one of the many things that just kept repeating itself. I think I enjoyed Paradise the most because it got philosophical in a way the others didn't as much, and I found that to be more interesting then hearing the name of yet another person I do not know or care existed. Even someone who is no longer a Christian myself found the theological discussions fascinating.

I also admit that this edition was slightly off-putting in two ways. One, the footnotes were a little crazy -- sometimes having like 12 of them on a page and giving us a footnote to read when it was very clear from the text what was being referenced, and other times when I was totally lost and unsure about some obscure word or person there was no footnote at all. There was definitely a judgmental tone in some of the footnote comments in the Inferno, and the author's Christian bias definitely peaked through (I remember something about the centaurs and what seemed to be the author's comment on their perverse-ness). Also, having the summary at the very beginning of each canto was a little odd -- it took me three cantos at the beginning of the book to realize that I didn't need to read the summary there, or else I would re-read it in the canto's text. I wonder why they didn't put the summary after? Though I do admit, that while I spent 98% of the book skipping these summaries, every once in a while when there was a particularly difficult passage, it was helpful to have those and read it to see if it could illuminate what was happening. I found I did this most with the Paradise section of the book. Still, it makes more sense after the canto's text is complete, instead of before, in my head.

Overall, it was a challenging, at times boring, at times exciting, read, and I'm glad I finally took the time to go through and put this one in my "read" shelf.

For me, I enjoyed Inferno and Paradise -- the latter which shocked me, because even the additional materials said that Paradise was the most difficult to get behind and "modern readers" wouldn't appreciate it. Inferno was fascinating to see the punishments, and the descriptions and language used is fascinating. BY the time I'd reached Purgatory, though, I was less enthused, and there was the fatigue of "how many more times is Dante going to be shy about asking a question, spend 30 lines writing about it, only to be told they already know what question he will ask" or "how many more times is he going to tell me how hard it is to write this" or one of the many things that just kept repeating itself. I think I enjoyed Paradise the most because it got philosophical in a way the others didn't as much, and I found that to be more interesting then hearing the name of yet another person I do not know or care existed. Even someone who is no longer a Christian myself found the theological discussions fascinating.

I also admit that this edition was slightly off-putting in two ways. One, the footnotes were a little crazy -- sometimes having like 12 of them on a page and giving us a footnote to read when it was very clear from the text what was being referenced, and other times when I was totally lost and unsure about some obscure word or person there was no footnote at all. There was definitely a judgmental tone in some of the footnote comments in the Inferno, and the author's Christian bias definitely peaked through (I remember something about the centaurs and what seemed to be the author's comment on their perverse-ness). Also, having the summary at the very beginning of each canto was a little odd -- it took me three cantos at the beginning of the book to realize that I didn't need to read the summary there, or else I would re-read it in the canto's text. I wonder why they didn't put the summary after? Though I do admit, that while I spent 98% of the book skipping these summaries, every once in a while when there was a particularly difficult passage, it was helpful to have those and read it to see if it could illuminate what was happening. I found I did this most with the Paradise section of the book. Still, it makes more sense after the canto's text is complete, instead of before, in my head.

Overall, it was a challenging, at times boring, at times exciting, read, and I'm glad I finally took the time to go through and put this one in my "read" shelf.

I don’t enjoy reading something that I need to translate to modern english only to not understand.

thought i would read it for school purposes but uhhh do not want to do that! may come back to it one day

Finished Inferno. Difficult read with lots of historical context and background notes

The Divine Comedy was a very interesting read. It's the kind of story you see return in some form in movies, books, games or music, particularly Dante's Inferno. I was mostly interested in reading it because I wanted to see what The Divine Comedy is all about and why it was so influential. However, Longfellow's translation was definitely the wrong choice for me. It felt like a very literal translation of each canto and it just didn't work for me. I can see the worth in having a literal translation of each Canto, a kind of "preservation across languages", but I feel like it just loses the spirit of the text for a lack of a better word. I wish I would have read a more poetic translation than a literal one.

I also would have liked an explanation at the end of each canto, which I know certain editions of the Divine Comedy have. Mine had none of that (I have the Barnes and Noble collectible hardcover) and some context would have helped with the more local figures Dante meets throughout his journey. The illustrations were beautiful though and helped paint an image of the things Dante encounters. All in all, I'm glad I got to read the Divine Comedy at last, but I regret not looking into the different translations more because I would have avoided Longfellow's or Norton's translation.

I also would have liked an explanation at the end of each canto, which I know certain editions of the Divine Comedy have. Mine had none of that (I have the Barnes and Noble collectible hardcover) and some context would have helped with the more local figures Dante meets throughout his journey. The illustrations were beautiful though and helped paint an image of the things Dante encounters. All in all, I'm glad I got to read the Divine Comedy at last, but I regret not looking into the different translations more because I would have avoided Longfellow's or Norton's translation.

I really liked the Inferno, the first of the three books of the Comedy. The journey through the nine circles of Hell was particularly interesting in how Dante organized the various sins and what he ranked as worse or lesser crimes. I found Purgatory and Paradise to be difficult to follow, with so many contemporaries of Dante’s mixed with noteworthy historical figures who I didn’t know. The translation seemed decent, although it converted Dante’s poem into prose. I admired the scholarship, imagination and conceptualisation of the piece, even if I wasn’t often expert enough to appreciate its content.

Read a few cantos from inferno and will come back to it. Very interesting and hard to dissect but fascinating, especially the history of it.

Speaking of Dante, Erich Auerbach stated, "we come to the conclusion that this man used language to discover the world anew." (Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature, 183)

Psychological development of subjects in literature is far from the exclusive technique of the novel because authors like Dante were exploring it long before Cervantes. Though the Divine Comedy is a didactic poem, composed between 1308-1320, perhaps most recognized for Dante's creation of mortal terror as well as revelatory sublimity, the pilgrim experiences a remarkable amount of self-reported personal and spiritual growth on his journey. His incredible spiritual growth in Paradiso is bestowed upon him, but he struggles with doubts and questions up to that point throughout all three canticles. As a reader, it is really incredible to join with him in his grief over his city becoming something he doesn't like while at the same time lamenting his banishment from said city, the state of the church, longing for a lost love, wondering why there is such evil in the world if there is a god, trying to represent something real and lasting artistically, and trying to understand God's logic with issues such as free will and preordination. Essentially, the final answer in the Divine Comedy to many of these questions is that God is perfect and whatever doesn't seem perfect is something we cannot understand. Though I don't have the kind of faith to accept this answer or find it useful, I thrilled as a reader with the way he continued to ask these questions as he went through Infierno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso.

Since there are autobiographical aspects to his work, I feel comfortable adding some things that have happened in my life that drew me to this book in the first place and greatly influenced my reading of the work. My husband and I have been on a journey through Latin America this year and I was reading the book on the second half of the journey that began after we spent two months with my sisters dealing with my parents' estate. My father died in his sleep this past December two years and two months after my mother died. He was still very much in love with her and really never got over the pain of losing her to cancer. They were both people of faith. Now my reading buddies know why I cried when Dante saw Beatrice. I could just picture my father's spirit beholding my mother's after their long separation and him experiencing the love of God through her image. As far as the journey aspect, I enjoyed reading about Dante feeling tired from climbing up the mountain in Purgatorio while we were hiking in Torres del Paine. He's quite correct that looking back at where you have come can be inspiring.

I had issues with Infierno. Of course, it is necessary in the whole cycle but I enjoyed it least for various reasons. Generally, the whole concept of disgusting eternal punishments is just too much for me. I don't accept this as fitting the concept of a loving God. Also, some of the sins aren't sins to me such as homosexuality or having other beliefs. I really hated the depiction of Muhammed in hell - one of the most gratuitously disgusting punishments. On the other hand, it was amusing to observe how he put certain enemies or literary rivals in hell without evidence of their crimes or sins and incredibly bold to put various arguably sinister popes there. The idea that those in hell chose their own fate and probably wouldn't even like heaven was very thought provoking. Also, his arrangement of severity of crimes fascinated me. Lust and violence are much less serious than theft or treachery. Lust and violence are natural, but theft is calculated. If penal codes matched divine justice according to Dante, executives who defraud their investors would go to jail for a much longer time than murderers. Though there was plenty of fire and torture, the stillness, silence and frigidity at the very bottom of hell was perfect.

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5764966f/f450.highres

Limbo is exceedingly problematic and this is dramatized in Virgil's residence there and his very sudden return there from Purgatorio after Dante reaches Beatrice. Virgil can't reside in Paradiso because he didn't believe in Christ, even though he died before the birth of Christ, which begs the question of why someone who had no chance of knowing about Christianity should be sent to this sub-section of Hell. This question was reintroduced to my great satisfaction in Cantos XIX and XX of Paradiso. First, Dante pushes the question of why people who couldn't have known Jesus should go to hell by having the eagle, collective spirit of the souls in Jupiter, repeat a question that Dante has asked in the past:

"‘A man is born in sight of Indus’ water, and there is none there to speak of Christ, . . . and he does not sin either in word or deed. He dies unbaptized and cannot receive the saving faith. What justice is it

damns him? Is it his fault that he does not believe?" Paradiso, XIX, 47-52

This question still haunts him most likely because of his tenderness for Virgil and he asks it even though he knows the answer will be that he cannot possibly understand God's justice and he must simply have faith. Though I really do appreciate his question, this whole line of reasoning is very messy. Dante is, of course, saying and clearly believes that Christianity is the only true religion. He isn't saying, for example, that there could be other divine paths. He might merely be suggesting, perhaps, that if Christianity is to be universal it should be spread everywhere. I guess this is some kind of call to arms for missionaries. What's odd about this question is that there wasn't any suggestion that there were any souls from the "Indus' waters" in limbo. I only recall unbaptized babies, Greeks and Romans for the most part in limbo. None of the levels of the afterworld seem to house anyone but those from Europe, Palestine, or Arabia (Biblical and Classical world and his contemporary Europe). My conclusion is that the afterworld Dante depicts is not universal to the modern reader. Though the 'world' to him was much smaller, there is still an obvious contradiction between his question about the virtuous man from India and his afterworld.

Next, in Canto XX, Dante extends the theme of interrogating divine justice while also dramatizing a testing of faith by presenting a soul who went to hell and was brought back to life in order to become a Christian and Ripheus, a Trojan, as shining in the eyebrow of the eagle who speaks to him in the realm of Jupiter.

Here is the discussion about Ripheus.

"Who would believe in the erring world down there that Ripheus the

Trojan would be sixth among the sacred lusters of this sphere?

Now he knows grace divine to depths of bliss the world’s poor understanding cannot grasp." Paradiso, XX, 45-48

In the previous Canto, he was just told that one has to know Christ in life to be saved so it is no wonder he might be confused by this or even question God's will. He can't help but ask.

"I could not bear to wait in silence there;

but from my tongue burst out “How can this be?”

forced by the weight of my own inner doubt." XX, 54-56

He is being tested, but the answer given reveals more of the depth or complexity of Divine Justice:

Ripheus "gave all his love to justice, there on earth, and God, by grace on grace, let him foresee a vision of our redemption shining forth . . . So he believed in Christ . . . More than a thousand years before the grace of baptism was known" XX, 81-83,85

This revelation changes the rules just a bit and Dante is forced to accept it rather than attack the logical inconsistencies. The eagle concludes with a spiritual lesson connected to the story of Ripheus:

"Not even we who look on God in Heaven

know, as yet, how many He will choose for ecstasy.

And sweet it is to lack this knowledge still, for in this good

is our own good refined, willing whatever God Himself may will." XX, 88-91

In my unorthodox interpretation, this leaves an opening for Virgil to be saved in the end of days based on God's will that surpasses human understanding. Dante isn't exactly towing the party line.

Our discussion of the Divine Comedy in this goodreads groups was very much enhanced by numerous discussions of the influences of Islamic writing and Arabic scholarship on Dante's work essentially ignored by the majority of Dante scholars. I read Surat Al-'Isrā' (The Night Journey) from the Quran and could see connections to Infierno in the idea that it is the choice of the unconverted to reject Paradise and prefer Hell, but I think I need to read the Miraaj and the criticism of Palacios in order to delve deeper into this rich vein of religious writing and its literary influence. There was also a really interesting connection between Purgatorio and the Conference of Birds, a Persian Sufi text written by Farid ud-Din Attar in 1177. I have read an Uzbek version of the text translated into English and there are clear comparisons that I noted due to Dante's abundant use of imagery of birds and flight. An even more clear connection to Islam for me is that the way Dante writes about his love for Beatrice that reminds me more of the representation of God as the beloved in Sufi writing than the depiction of platonic love by Medieval troubadours. The Divine Comedy can be interpreted as a love allegory. His love for Beatrice is a manifestation of his worship of divine revelation and also functions perfectly well as love poetry.

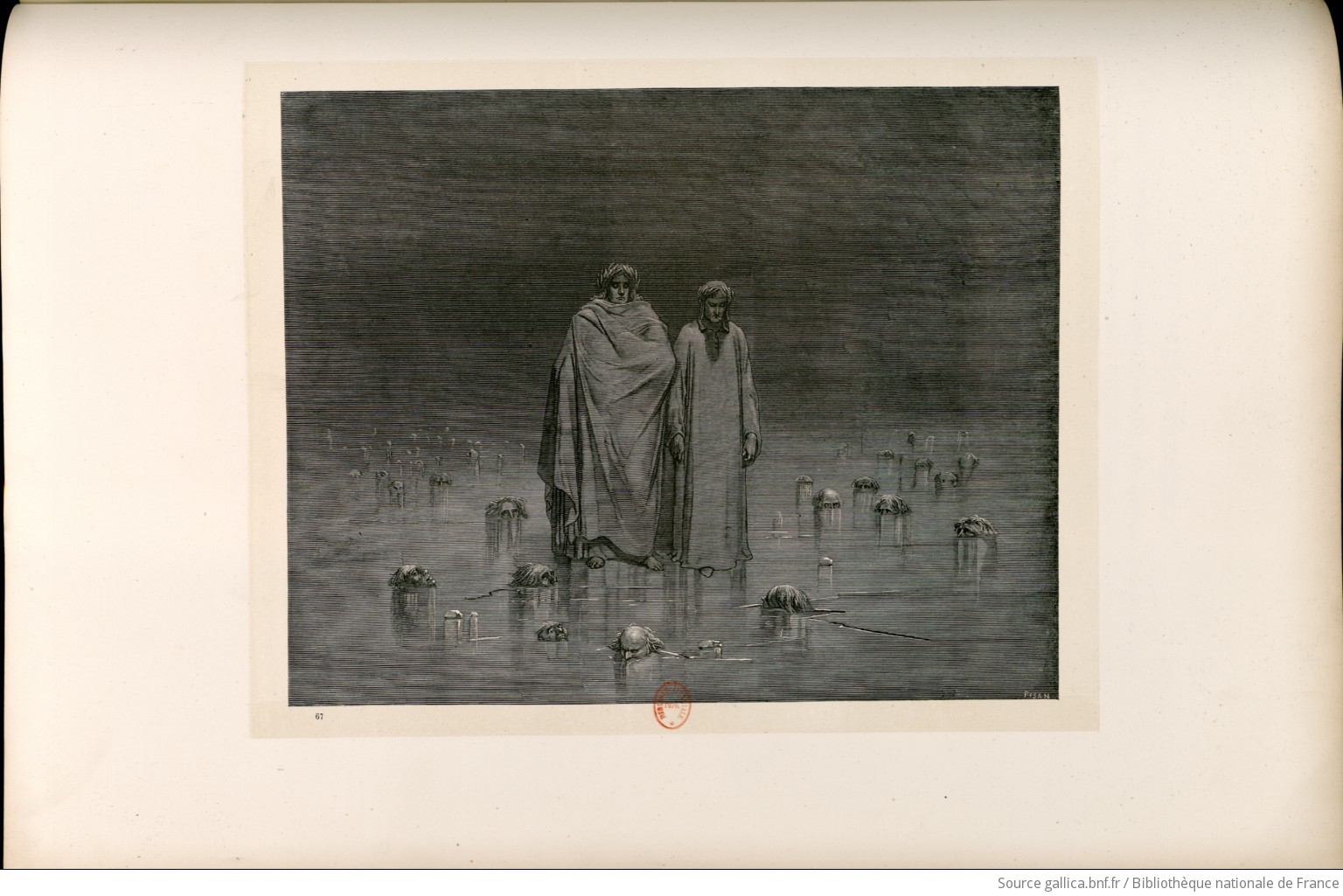

The accurate representation of his journey to the reader is a constant difficulty that Dante dramatizes even though he is imaging every last bit of it. Considering this, it is marvelous that the difficulty of representation is so poignant in the work. Rivalries between authors and artists centered on their ability to portray and beautify reality are alluded to at certain points. One of my favorite parts of the Divine Comedy regarding pride of talent and the difficulty of representation is in Purgatorio where Dante is awed by the divinely created marble reliefs that form the Whip of Pride depicting three scenes of great people showing humility. No human can compete with this art and he doesn't even try to fully describe it, but communicates his appreciation for it by suggesting that the angel is so real that he can almost hear him speaking. He goes further with the next relief by expresses that he is truly confused as to whether he can hear the choir singing or not. Dante's use of synesthesia is used to very good effect here and seems innovative. The question of representation constantly occurs to me when confronted with the amazingly rich tradition of visual artists painting scenes from the Divine Comedy. Here is a depiction of the reliefs in question by a daring painter.

In the end, Dante takes a mystical direction in the end of Paradiso, and he plays with time to aid him in this project as he continues to draw in the reader. At many points along his journey, especially when he was with Virgil, he was reminded that he needed to hurry up or continue to the next level, that his time was limited. This was a rather amusing detail, seemingly irrelevant for the majority of the work. However, in Canto XXXII of Paradiso I realized that the time he was left, as he approaches the Empyrean is suddenly woefully insufficient. It is painful to think of him leaving paradise. Then Dante does something wonderful in the final canto (XXXIII). Once the pilgrim gets to the Empyrean and beholds the light of God, the narration indicates a quality of timelessness in his experience with that light. It really is mystical. However, in one of the most poignant moments of the Divine Comedy, he makes it clear that he can't fully recall this momentary transcendence, or satori, any longer.

"The ravished memory swoons and falls away.

As one who sees in dreams and wakes to find the emotional impression

of his vision still powerful while its parts fade from his mind—" Paradiso, XXXIII, 38-40

This is an evocation of the Portuguese concept of "saudade," longing for and missing something that you can't have, but feeling the love of that thing. The difference is that Dante fully expects to behold it again after his death.

Thank you to Book Portrait for finding all of the pictures I use here.

Psychological development of subjects in literature is far from the exclusive technique of the novel because authors like Dante were exploring it long before Cervantes. Though the Divine Comedy is a didactic poem, composed between 1308-1320, perhaps most recognized for Dante's creation of mortal terror as well as revelatory sublimity, the pilgrim experiences a remarkable amount of self-reported personal and spiritual growth on his journey. His incredible spiritual growth in Paradiso is bestowed upon him, but he struggles with doubts and questions up to that point throughout all three canticles. As a reader, it is really incredible to join with him in his grief over his city becoming something he doesn't like while at the same time lamenting his banishment from said city, the state of the church, longing for a lost love, wondering why there is such evil in the world if there is a god, trying to represent something real and lasting artistically, and trying to understand God's logic with issues such as free will and preordination. Essentially, the final answer in the Divine Comedy to many of these questions is that God is perfect and whatever doesn't seem perfect is something we cannot understand. Though I don't have the kind of faith to accept this answer or find it useful, I thrilled as a reader with the way he continued to ask these questions as he went through Infierno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso.

Since there are autobiographical aspects to his work, I feel comfortable adding some things that have happened in my life that drew me to this book in the first place and greatly influenced my reading of the work. My husband and I have been on a journey through Latin America this year and I was reading the book on the second half of the journey that began after we spent two months with my sisters dealing with my parents' estate. My father died in his sleep this past December two years and two months after my mother died. He was still very much in love with her and really never got over the pain of losing her to cancer. They were both people of faith. Now my reading buddies know why I cried when Dante saw Beatrice. I could just picture my father's spirit beholding my mother's after their long separation and him experiencing the love of God through her image. As far as the journey aspect, I enjoyed reading about Dante feeling tired from climbing up the mountain in Purgatorio while we were hiking in Torres del Paine. He's quite correct that looking back at where you have come can be inspiring.

I had issues with Infierno. Of course, it is necessary in the whole cycle but I enjoyed it least for various reasons. Generally, the whole concept of disgusting eternal punishments is just too much for me. I don't accept this as fitting the concept of a loving God. Also, some of the sins aren't sins to me such as homosexuality or having other beliefs. I really hated the depiction of Muhammed in hell - one of the most gratuitously disgusting punishments. On the other hand, it was amusing to observe how he put certain enemies or literary rivals in hell without evidence of their crimes or sins and incredibly bold to put various arguably sinister popes there. The idea that those in hell chose their own fate and probably wouldn't even like heaven was very thought provoking. Also, his arrangement of severity of crimes fascinated me. Lust and violence are much less serious than theft or treachery. Lust and violence are natural, but theft is calculated. If penal codes matched divine justice according to Dante, executives who defraud their investors would go to jail for a much longer time than murderers. Though there was plenty of fire and torture, the stillness, silence and frigidity at the very bottom of hell was perfect.

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5764966f/f450.highres

Limbo is exceedingly problematic and this is dramatized in Virgil's residence there and his very sudden return there from Purgatorio after Dante reaches Beatrice. Virgil can't reside in Paradiso because he didn't believe in Christ, even though he died before the birth of Christ, which begs the question of why someone who had no chance of knowing about Christianity should be sent to this sub-section of Hell. This question was reintroduced to my great satisfaction in Cantos XIX and XX of Paradiso. First, Dante pushes the question of why people who couldn't have known Jesus should go to hell by having the eagle, collective spirit of the souls in Jupiter, repeat a question that Dante has asked in the past:

"‘A man is born in sight of Indus’ water, and there is none there to speak of Christ, . . . and he does not sin either in word or deed. He dies unbaptized and cannot receive the saving faith. What justice is it

damns him? Is it his fault that he does not believe?" Paradiso, XIX, 47-52

This question still haunts him most likely because of his tenderness for Virgil and he asks it even though he knows the answer will be that he cannot possibly understand God's justice and he must simply have faith. Though I really do appreciate his question, this whole line of reasoning is very messy. Dante is, of course, saying and clearly believes that Christianity is the only true religion. He isn't saying, for example, that there could be other divine paths. He might merely be suggesting, perhaps, that if Christianity is to be universal it should be spread everywhere. I guess this is some kind of call to arms for missionaries. What's odd about this question is that there wasn't any suggestion that there were any souls from the "Indus' waters" in limbo. I only recall unbaptized babies, Greeks and Romans for the most part in limbo. None of the levels of the afterworld seem to house anyone but those from Europe, Palestine, or Arabia (Biblical and Classical world and his contemporary Europe). My conclusion is that the afterworld Dante depicts is not universal to the modern reader. Though the 'world' to him was much smaller, there is still an obvious contradiction between his question about the virtuous man from India and his afterworld.

Next, in Canto XX, Dante extends the theme of interrogating divine justice while also dramatizing a testing of faith by presenting a soul who went to hell and was brought back to life in order to become a Christian and Ripheus, a Trojan, as shining in the eyebrow of the eagle who speaks to him in the realm of Jupiter.

Here is the discussion about Ripheus.

"Who would believe in the erring world down there that Ripheus the

Trojan would be sixth among the sacred lusters of this sphere?

Now he knows grace divine to depths of bliss the world’s poor understanding cannot grasp." Paradiso, XX, 45-48

In the previous Canto, he was just told that one has to know Christ in life to be saved so it is no wonder he might be confused by this or even question God's will. He can't help but ask.

"I could not bear to wait in silence there;

but from my tongue burst out “How can this be?”

forced by the weight of my own inner doubt." XX, 54-56

He is being tested, but the answer given reveals more of the depth or complexity of Divine Justice:

Ripheus "gave all his love to justice, there on earth, and God, by grace on grace, let him foresee a vision of our redemption shining forth . . . So he believed in Christ . . . More than a thousand years before the grace of baptism was known" XX, 81-83,85

This revelation changes the rules just a bit and Dante is forced to accept it rather than attack the logical inconsistencies. The eagle concludes with a spiritual lesson connected to the story of Ripheus:

"Not even we who look on God in Heaven

know, as yet, how many He will choose for ecstasy.

And sweet it is to lack this knowledge still, for in this good

is our own good refined, willing whatever God Himself may will." XX, 88-91

In my unorthodox interpretation, this leaves an opening for Virgil to be saved in the end of days based on God's will that surpasses human understanding. Dante isn't exactly towing the party line.

Our discussion of the Divine Comedy in this goodreads groups was very much enhanced by numerous discussions of the influences of Islamic writing and Arabic scholarship on Dante's work essentially ignored by the majority of Dante scholars. I read Surat Al-'Isrā' (The Night Journey) from the Quran and could see connections to Infierno in the idea that it is the choice of the unconverted to reject Paradise and prefer Hell, but I think I need to read the Miraaj and the criticism of Palacios in order to delve deeper into this rich vein of religious writing and its literary influence. There was also a really interesting connection between Purgatorio and the Conference of Birds, a Persian Sufi text written by Farid ud-Din Attar in 1177. I have read an Uzbek version of the text translated into English and there are clear comparisons that I noted due to Dante's abundant use of imagery of birds and flight. An even more clear connection to Islam for me is that the way Dante writes about his love for Beatrice that reminds me more of the representation of God as the beloved in Sufi writing than the depiction of platonic love by Medieval troubadours. The Divine Comedy can be interpreted as a love allegory. His love for Beatrice is a manifestation of his worship of divine revelation and also functions perfectly well as love poetry.

The accurate representation of his journey to the reader is a constant difficulty that Dante dramatizes even though he is imaging every last bit of it. Considering this, it is marvelous that the difficulty of representation is so poignant in the work. Rivalries between authors and artists centered on their ability to portray and beautify reality are alluded to at certain points. One of my favorite parts of the Divine Comedy regarding pride of talent and the difficulty of representation is in Purgatorio where Dante is awed by the divinely created marble reliefs that form the Whip of Pride depicting three scenes of great people showing humility. No human can compete with this art and he doesn't even try to fully describe it, but communicates his appreciation for it by suggesting that the angel is so real that he can almost hear him speaking. He goes further with the next relief by expresses that he is truly confused as to whether he can hear the choir singing or not. Dante's use of synesthesia is used to very good effect here and seems innovative. The question of representation constantly occurs to me when confronted with the amazingly rich tradition of visual artists painting scenes from the Divine Comedy. Here is a depiction of the reliefs in question by a daring painter.

In the end, Dante takes a mystical direction in the end of Paradiso, and he plays with time to aid him in this project as he continues to draw in the reader. At many points along his journey, especially when he was with Virgil, he was reminded that he needed to hurry up or continue to the next level, that his time was limited. This was a rather amusing detail, seemingly irrelevant for the majority of the work. However, in Canto XXXII of Paradiso I realized that the time he was left, as he approaches the Empyrean is suddenly woefully insufficient. It is painful to think of him leaving paradise. Then Dante does something wonderful in the final canto (XXXIII). Once the pilgrim gets to the Empyrean and beholds the light of God, the narration indicates a quality of timelessness in his experience with that light. It really is mystical. However, in one of the most poignant moments of the Divine Comedy, he makes it clear that he can't fully recall this momentary transcendence, or satori, any longer.

"The ravished memory swoons and falls away.

As one who sees in dreams and wakes to find the emotional impression

of his vision still powerful while its parts fade from his mind—" Paradiso, XXXIII, 38-40

This is an evocation of the Portuguese concept of "saudade," longing for and missing something that you can't have, but feeling the love of that thing. The difference is that Dante fully expects to behold it again after his death.

Thank you to Book Portrait for finding all of the pictures I use here.

On my second reading of it, this book made so much more sense than it had at first. Dante makes his way through Purgatory with his guide, Virgil, and reaches the Earthly Paradise, Eden, where he encounters his beloved Beatrice.

This latter portion of the text is especially strange, with visions, metaphors and allegory. Hang on in there!

This latter portion of the text is especially strange, with visions, metaphors and allegory. Hang on in there!