You need to sign in or sign up before continuing.

Take a photo of a barcode or cover

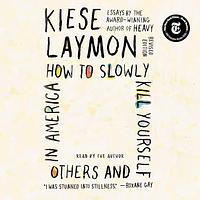

A collection of essays that trace coping mechanisms, intergenerational trauma, and resilience in gorgeous prose. In my favorite essay, Kiese sets Kanye West beside his grandpa Les and questions whether any men truly deserve to be loved by women when, he implicates himself here: "I have intimately fucked up women's lives." I've had this book in my possession for months but wasn't ready before; when I picked it up this past week, I red it on three sittings. It was divine.

It really lost me. I really wanted this to be from the soul, but I think it was written from the mind instead. I am glad Kiese has survived after going through so much, but I lost the thread of the essays as we got further along. It didn't feel like a story, or a journey. This felt like a release for him personally as he broke down his past. So I'm glad it exists for his artistry and his records, but it didn't do too much for me.

Up top I want to say I love Kiese Laymon's "Heavy" and the pieces he's written thereafter as well as his podcast with Deesha Philyaw so I was excited to dive into his backlist. This book is an uneven and sometimes circular collection that hits the mark more often that it misses. Kiese plays with form in ways that don't always work, but I commend the ways he uses letters, shared conversations and essays to grapple with what haunts him in terms of his relationships with his family, women, Mississippi and Blackness in relationship to America.

Kiese deals with the ways he has both been harmed and harmed others and the ways he's still learning to atone for that. He speaks into the gap between who you want to be and who you are. Sitting in this gap with him I found hard mirrors of my own. Kiese reminds us that we are "both wicked and wonderful."

I'm happy that this book introduced me to Kai M. Green. Kai's letter in the "Echo: Mychal, Kiese, Kai, and Marlon" chapter was so good I had to jump around the room a little bit. It packed an emotional punch that only comes from wisdom and authenticity. I'm also happy that Kiese got the chance to buy this collection back and release it in a way that feels good to him. I don't think it's as strong as "Heavy" and sometimes goes too far into virtue signaling, but he does stick the landing in the last three essays.

Kiese deals with the ways he has both been harmed and harmed others and the ways he's still learning to atone for that. He speaks into the gap between who you want to be and who you are. Sitting in this gap with him I found hard mirrors of my own. Kiese reminds us that we are "both wicked and wonderful."

I'm happy that this book introduced me to Kai M. Green. Kai's letter in the "Echo: Mychal, Kiese, Kai, and Marlon" chapter was so good I had to jump around the room a little bit. It packed an emotional punch that only comes from wisdom and authenticity. I'm also happy that Kiese got the chance to buy this collection back and release it in a way that feels good to him. I don't think it's as strong as "Heavy" and sometimes goes too far into virtue signaling, but he does stick the landing in the last three essays.

With a good analysis of race in America that produces this "slow death" Laymon is a modern day extension of great essayist James Baldwin but remixed for the hip hop generation. At times you laugh and others you feel heartbreak that America in the 21st century is still teaching It's citizens how to carry out the "slow death".

I read this again because the author bought the rights to his book back and released a revised edition of this book of the same title. Including the original essays, this book includes new essays that illuminates our current political moment while not losing the swagger of the original essays that we have come to love and expect from Laymon. Honestly reading this during this current political context just hit different and illuminated the world we live in differently. Even if you have read this before. Buy it and read it again.

I read this again because the author bought the rights to his book back and released a revised edition of this book of the same title. Including the original essays, this book includes new essays that illuminates our current political moment while not losing the swagger of the original essays that we have come to love and expect from Laymon. Honestly reading this during this current political context just hit different and illuminated the world we live in differently. Even if you have read this before. Buy it and read it again.

Sharp, honest, unapologetic, and unexpectedly relatable. A very interesting read.

If I ever desired to have a favorite writer, Kiese would be on my short list.

I found myself reliving many conversations, often in tents on the other side of the world, where my eyes - away from the myth of American exceptionalism and innocence, were opened. Guilty of the privileged sin of thinking I knew more than I did. The America not seen at tables of privilege was always a poorly kept secret. But still.

Still, I got to the essay titled 'Reasonable Doubt and the Lost Presidential Election of 2012' - and the sentence, "I also assumed most of those folks were wondering how retribution for this splendid Black American Achievement would be played out on their bodies" and realized the ugliness of American mythology was uglier than realized - centuries of seeing every moment of progress repaid with a violent backlash. And the need to stop overtalking what's being said and to just shut up and listen.

Kiese Laymon lays down these truths in a way that rips the veneer off the myth. It's storytelling at its finest that resists the urge to compartmentalize discussions of justice from discussions of family from discussions of joy from discussions of grief - showing how pervasive hate is. Even after a person has come to terms with its destructiveness, that's only the beginning of the learning process.

Kiese Laymon needs to be read at every level.

Still, I got to the essay titled 'Reasonable Doubt and the Lost Presidential Election of 2012' - and the sentence, "I also assumed most of those folks were wondering how retribution for this splendid Black American Achievement would be played out on their bodies" and realized the ugliness of American mythology was uglier than realized - centuries of seeing every moment of progress repaid with a violent backlash. And the need to stop overtalking what's being said and to just shut up and listen.

Kiese Laymon lays down these truths in a way that rips the veneer off the myth. It's storytelling at its finest that resists the urge to compartmentalize discussions of justice from discussions of family from discussions of joy from discussions of grief - showing how pervasive hate is. Even after a person has come to terms with its destructiveness, that's only the beginning of the learning process.

Kiese Laymon needs to be read at every level.

This is a collection of essays written by the author about various times in his life. Brilliantly written and so insightful about his experiences living in the south in Mississippi, as well as time spent in upstate New York. He's honest with sharing his struggles - some self-inflicted and some inflicted due to his race and the people he is surrounded by.

Kiese Laymon's book has twelve essays, including an Author Note & Prologue. This book goes to the heart and roots of being a black male from Mississippi.

In my favorite essay, "The Worst of White Folks," every time this phrase is repeated it is in italics. He brings us into the world of contemporary America through the history of his mother and grandmother, and the grandmothers of his friends. In these paragraphs, he nails our racial and political climate:

"Though my grandmother worked from the time she was seven years old, our nation forbade her from registering to vote until she was deep into her thirties. She has lived under American Apartheid longer than she's been technically "free." Our nation told her she world enter the chicken plant as a line worker and retire as a line worker, no matter how well she worked. Our nation limited the amount of formal education she herself could attain and patted her on the back when she earned enough to buy her daughters and son a set of encyclopedias. Our nation watched her raise four black children and two grandchildren to become teachers, all the while responsibly arming herself and her community against the worst of white folks and the destructive tendencies of neighbors.

Last month, after burying her brother, Rudy, Grandma bent her knees and reckoned with burying her son, her sisters, her mother, her grandmother, her father, and all four of her best friends. She asked her God to spare her the responsibility of burying any more of her children or grandchildren. A few weeks later, an irresponsible American aspiring to be the leader of our nation, who got a majority of the vote from the worst of white folks, caller her a "victim" who feels entitled to healthcare, food, and housing.

Catherine Coleman, along with my grandmother Pudding, and David Rozier's grandmother, have been allowed to just be victims. They're rarely even allowed to be Americans. They don't get invited to panel discussions. They aren't talked to by the DNC or the RNC. No one asks them what to do about national violence, debt, or defense. They are not American super women, but they are the best Americans. They have remained responsible, critical, and loving in the face of servitude, sexual assault, segregation, poverty, and psychological violence. They have done this hard, messy work because they were committed to life and justice, and so we all might live more responsibly tomorrow.

There is a price to pay for ducking responsibility, for clinging to the worst of us, for harboring a warped innocence. There is an ever greater price to pay for ignoring, demeaning, and unfairly burdening those Americans who have disproportionately borne the weight of American irresponsibility for so long. Our grandmothers and great-grandmothers have paid more than their fair share, and our nation owes them and their children, and their children's children a lifetime of healthy choices and second chances. That would be responsible."

In the essay, "Our Kind of Ridiculous," he uses the phrase "thirty cents away from a quarter." And continues his critique of the worst of white folks, "If white American entitlement meant anything, it meant that no matter how patronizing, unashamed, deliberate, unintentional, poor, rich, rural, urban, ignorant, and destructive white Americans were, black Americans were still encouraged to work for them, write to them, listen to them, talk with them, run from them, emulate them, teach them, dodge them, and ultimately thank them for not being as fucked up as they could be."

And here is what he wanted his white girlfriend to say, "...we were the collateral damage of a nation going through growth pains." After they were stopped while driving and he was nearly arrested for a bogus charge in rural Pennsylvania.

In the piece, "Echo: Mychal, Darnell, Kiese, Kai, and Marlon," it is a set of letters these men corresponded about their lives, Kiese writes, "Femiphobic diatribes and other bad books have gassed us with this idea that black boys need the presence of black father figures in our lives. I'm sure I'm not the only black boy who realized a long time ago that my mother and her mother and her mother's mother needed loving, generous partners far more than I needed a present father." And he comes to what they need, "Black children need waves of present, multifaceted love, not simply present fathers."

In the essay, "Reasonable Doubt and the Lost Presidential Debate of 2012," this quote resonates, "..., mama taught me that black Americans have always borne the brunt of domestic economic terrorism after supposed policy and political wins." Which speaks to our present situation after having a black president for eight years.

In the essay, "Tupac Amaru Shakur," a black performer and activist who was shot in 1996 at the age of 25, he writes, "...I knew intimately the ways that black American ambition, unchecked by healthy doses of fear, would lead to slow, painful death. This was our American story. I also knew that when enough rusty bullets were fired from traumatized citizens at moving black targets (no matter how passionate, willful, sensual, and imaginative those targets might be), the targets would eventually cease to exist."

Powerful political writing that needs to be read by all.

In my favorite essay, "The Worst of White Folks," every time this phrase is repeated it is in italics. He brings us into the world of contemporary America through the history of his mother and grandmother, and the grandmothers of his friends. In these paragraphs, he nails our racial and political climate:

"Though my grandmother worked from the time she was seven years old, our nation forbade her from registering to vote until she was deep into her thirties. She has lived under American Apartheid longer than she's been technically "free." Our nation told her she world enter the chicken plant as a line worker and retire as a line worker, no matter how well she worked. Our nation limited the amount of formal education she herself could attain and patted her on the back when she earned enough to buy her daughters and son a set of encyclopedias. Our nation watched her raise four black children and two grandchildren to become teachers, all the while responsibly arming herself and her community against the worst of white folks and the destructive tendencies of neighbors.

Last month, after burying her brother, Rudy, Grandma bent her knees and reckoned with burying her son, her sisters, her mother, her grandmother, her father, and all four of her best friends. She asked her God to spare her the responsibility of burying any more of her children or grandchildren. A few weeks later, an irresponsible American aspiring to be the leader of our nation, who got a majority of the vote from the worst of white folks, caller her a "victim" who feels entitled to healthcare, food, and housing.

Catherine Coleman, along with my grandmother Pudding, and David Rozier's grandmother, have been allowed to just be victims. They're rarely even allowed to be Americans. They don't get invited to panel discussions. They aren't talked to by the DNC or the RNC. No one asks them what to do about national violence, debt, or defense. They are not American super women, but they are the best Americans. They have remained responsible, critical, and loving in the face of servitude, sexual assault, segregation, poverty, and psychological violence. They have done this hard, messy work because they were committed to life and justice, and so we all might live more responsibly tomorrow.

There is a price to pay for ducking responsibility, for clinging to the worst of us, for harboring a warped innocence. There is an ever greater price to pay for ignoring, demeaning, and unfairly burdening those Americans who have disproportionately borne the weight of American irresponsibility for so long. Our grandmothers and great-grandmothers have paid more than their fair share, and our nation owes them and their children, and their children's children a lifetime of healthy choices and second chances. That would be responsible."

In the essay, "Our Kind of Ridiculous," he uses the phrase "thirty cents away from a quarter." And continues his critique of the worst of white folks, "If white American entitlement meant anything, it meant that no matter how patronizing, unashamed, deliberate, unintentional, poor, rich, rural, urban, ignorant, and destructive white Americans were, black Americans were still encouraged to work for them, write to them, listen to them, talk with them, run from them, emulate them, teach them, dodge them, and ultimately thank them for not being as fucked up as they could be."

And here is what he wanted his white girlfriend to say, "...we were the collateral damage of a nation going through growth pains." After they were stopped while driving and he was nearly arrested for a bogus charge in rural Pennsylvania.

In the piece, "Echo: Mychal, Darnell, Kiese, Kai, and Marlon," it is a set of letters these men corresponded about their lives, Kiese writes, "Femiphobic diatribes and other bad books have gassed us with this idea that black boys need the presence of black father figures in our lives. I'm sure I'm not the only black boy who realized a long time ago that my mother and her mother and her mother's mother needed loving, generous partners far more than I needed a present father." And he comes to what they need, "Black children need waves of present, multifaceted love, not simply present fathers."

In the essay, "Reasonable Doubt and the Lost Presidential Debate of 2012," this quote resonates, "..., mama taught me that black Americans have always borne the brunt of domestic economic terrorism after supposed policy and political wins." Which speaks to our present situation after having a black president for eight years.

In the essay, "Tupac Amaru Shakur," a black performer and activist who was shot in 1996 at the age of 25, he writes, "...I knew intimately the ways that black American ambition, unchecked by healthy doses of fear, would lead to slow, painful death. This was our American story. I also knew that when enough rusty bullets were fired from traumatized citizens at moving black targets (no matter how passionate, willful, sensual, and imaginative those targets might be), the targets would eventually cease to exist."

Powerful political writing that needs to be read by all.

powerful and important. an incredibly truthful essays detailing accounts of race, identity, and lack of self-love in our daily relationships with each other and ourselves.

a few of the essays reminded me of baldwin and the fierceness with which he wrote.

a few of the essays reminded me of baldwin and the fierceness with which he wrote.