Take a photo of a barcode or cover

65 reviews for:

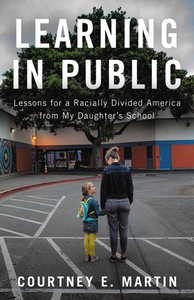

Learning in Public: Lessons for a Racially Divided America from My Daughter's School

Courtney E. Martin

65 reviews for:

Learning in Public: Lessons for a Racially Divided America from My Daughter's School

Courtney E. Martin

Appreciated author being conscious and mindful about virtue signaling and acting as a white savior. She handles the complex and systemic problems within our education systems with grace and thoughtfulness and tries make changes. She shows up in many ways for her community and her family and I’m thankful she is bringing attention to some of the problems.

This book is very well done- very good research and also readable for regular people.

I decided not to finish because the context is so different from mine, and it's also very long and I have too many other books to read.

I decided not to finish because the context is so different from mine, and it's also very long and I have too many other books to read.

Courtney Martin's writing style is so easy to read, and the school debate is near and dear to my heart. This book hit home for me and made me think a lot about the choices parents make and the choices I've personally made as a parent. I would love to sit down and have coffee with Martin and talk for hours about the issues she explores in her book. And also about co-housing because, what?! This way of living exists? I am so intrigued. I heard about this book on a podcast and Martin mentioned the cohousing and I was sold.

Basically, Martin takes the subject of how White people (mostly) deal with school for their children and explores the heck out of it. It's not pretty in places. Within this context, Martin is making and living with the decision to send her White daughter to the primarily Black (and "underperforming") neighborhood school. This book didn't make me feel guilty about being White (Martin does not pull punches when it comes to crtiquing White privilege), but it made me think a lot about it, and as Jia Tolentino would say, reflect on self-delusion. Martin sterotypes White liberals and wow, do I fit that stereotype! And she questions how far White liberals are willing to go to uphold their professed beliefs, which is something I've been thinking a lot about lately. This book hit the sweet spot for me in terms of what I've been thinking about/wrestling with lately, so it was a great read.

Basically, Martin takes the subject of how White people (mostly) deal with school for their children and explores the heck out of it. It's not pretty in places. Within this context, Martin is making and living with the decision to send her White daughter to the primarily Black (and "underperforming") neighborhood school. This book didn't make me feel guilty about being White (Martin does not pull punches when it comes to crtiquing White privilege), but it made me think a lot about it, and as Jia Tolentino would say, reflect on self-delusion. Martin sterotypes White liberals and wow, do I fit that stereotype! And she questions how far White liberals are willing to go to uphold their professed beliefs, which is something I've been thinking a lot about lately. This book hit the sweet spot for me in terms of what I've been thinking about/wrestling with lately, so it was a great read.

challenging

hopeful

informative

inspiring

medium-paced

challenging

emotional

hopeful

informative

inspiring

reflective

sad

slow-paced

Reading this was difficult in ways I did not expect. I believe in and practice school integration, and I can relate to the author in many ways. I've had those awkward, cringe-worthy interactions across lines of difference where I am trying my best but failing to see so many pitfalls caused by my own biases. And I am a patreon of the author's newsletter; I generally find her very inspiring and contemplative. So it was a surprise to me that I had so many big feelings reading this.

I was not expecting the book to be so detailed in putting not only the author's journey and mess out there, but the journeys and mess of the other players in the book . . . the disabled single Black dad, the aggressive white mom who feels entitled to tell the principal and teacher how to do their jobs (who winds up being an obvious foil to the author), the inscrutable Black preK teacher. I believe the author had their permission and presented herself as a journalist who was trying to report on this as objectively as possible, but I was surprised to discover that she didn't change the names of the schools or anyone who was even remotely a public figure.

Perhaps because I could relate so much to the author's experiences, I was imagining if I were putting out the words and actions of my principal, my kids' teachers, the parents whom I befriend, etc. in a book. It felt invasive and exploitative, literally making money off of sharing these things. And knowing that these events all happened within the last couple of years only magnified that feeling. How can you painstakingly build trust despite systemic obstacles and power imbalances if you are recording and publishing everything your newfound friend says?

Maybe it was the author's journalism background that convinced her to be so detailed in sharing her interactions with other players, but I wish she had taken more of a general view. If journalism was her goal, she could have interviewed other parents experiencing segregation and integration from different viewpoints. But to write a detailed memoir about this subject, I think it would have been best to wait for more distance from the events (if my math is correct, her oldest is only starting 2nd grade). It took the founder of Integrated Schools many years to feel emboldened to guide others.

I do appreciate that she did the work of asking for feedback from a Black mentor, but I can see the point of Danzy Senna in her review in the Atlantic when she says, "The world these writers [Martin and Robin DiAngelo] evoke is one in which white people remain the center of the story and Black people are at the margins, poor, stiff, and dignified, with little better to do than open their homes and hearts to white women on journeys to racial self-awareness." On one hand, I love that Martin was so honest and retained the turns of phrase where her bias came out (calling the single dad a "creature"), but on the other, I can imagine prospective integrators thinking, "Well shoot, I don't have a Black PhD waiting to give feedback on my every move . . . should I give up before I start?" Most importantly, I don't think ANY white person should expect to be shepherded by people of color.

In full disclosure, it could just be me. I am not a memoir reader; I haven't even read the Obamas' memoirs. Maybe I got too into my head; maybe I don't like being in other people's heads. If you are someone who finds joy and inspiration reading memoirs, or if you are someone who doesn't know much about segregation or the common pitfalls to practicing antiracist school integration, then this book may be just for you.

What I did like . . . the history and sociology, the more creative sections (poems and important phrases repeated many times), the awareness brought to the evil of segregation. I see positive reviews and I am thankful that my experience is not universal. I know that privileged white folks need to say, hey, hello, I have been hugely oblivious to my biases and here's how I'm learning to spot them and change direction. It's important and necessary. I just wish it had been done in a different way.

ETA: One more area that weighed heavily on my heart was the portrayal of the author as the emotional support of the teachers during the pandemic, and her end note that she'll see the teachers "on the field at sunset."

I attended a workshop with the late Courtney Mykytyn, founder of Integrated Schools, and she was very adamant that white parents *not* be the BFF of the teacher because that's a white parent thing. I was a teacher and goodness knows they need support, but the white parent as a texting buddy of the teacher, as a *peer* and friend, is part of white supremacy culture and further perpetuates power imbalances when that's not the expectation or position held by Black and Brown parents. If there's a wish list I quietly buy from it, but I try to maintain a professional distance from the teachers and staff.

It's all well and good to aim for self-awareness, to struggle over how to show up and how not to, but if in the end you're the PTA president and have made yourself integral to the entire staff, is it OK to perpetuate white supremacy culture patterns because people just like you so darn much?

Again, I circle back to . . . this was too much, too soon. I wish the author well on her journey. I know she has a sharp mind and open heart.

Update Dec. 2022: I met a mom recently who was inspired by this book to pull her child from private school and put them in a hyper-segregated school. So again I thought, maybe it's just me. Maybe if you haven't been introduced to the idea of not putting your child in a privileged school, this book is a good starting point.

I was not expecting the book to be so detailed in putting not only the author's journey and mess out there, but the journeys and mess of the other players in the book . . . the disabled single Black dad, the aggressive white mom who feels entitled to tell the principal and teacher how to do their jobs (who winds up being an obvious foil to the author), the inscrutable Black preK teacher. I believe the author had their permission and presented herself as a journalist who was trying to report on this as objectively as possible, but I was surprised to discover that she didn't change the names of the schools or anyone who was even remotely a public figure.

Perhaps because I could relate so much to the author's experiences, I was imagining if I were putting out the words and actions of my principal, my kids' teachers, the parents whom I befriend, etc. in a book. It felt invasive and exploitative, literally making money off of sharing these things. And knowing that these events all happened within the last couple of years only magnified that feeling. How can you painstakingly build trust despite systemic obstacles and power imbalances if you are recording and publishing everything your newfound friend says?

Maybe it was the author's journalism background that convinced her to be so detailed in sharing her interactions with other players, but I wish she had taken more of a general view. If journalism was her goal, she could have interviewed other parents experiencing segregation and integration from different viewpoints. But to write a detailed memoir about this subject, I think it would have been best to wait for more distance from the events (if my math is correct, her oldest is only starting 2nd grade). It took the founder of Integrated Schools many years to feel emboldened to guide others.

I do appreciate that she did the work of asking for feedback from a Black mentor, but I can see the point of Danzy Senna in her review in the Atlantic when she says, "The world these writers [Martin and Robin DiAngelo] evoke is one in which white people remain the center of the story and Black people are at the margins, poor, stiff, and dignified, with little better to do than open their homes and hearts to white women on journeys to racial self-awareness." On one hand, I love that Martin was so honest and retained the turns of phrase where her bias came out (calling the single dad a "creature"), but on the other, I can imagine prospective integrators thinking, "Well shoot, I don't have a Black PhD waiting to give feedback on my every move . . . should I give up before I start?" Most importantly, I don't think ANY white person should expect to be shepherded by people of color.

In full disclosure, it could just be me. I am not a memoir reader; I haven't even read the Obamas' memoirs. Maybe I got too into my head; maybe I don't like being in other people's heads. If you are someone who finds joy and inspiration reading memoirs, or if you are someone who doesn't know much about segregation or the common pitfalls to practicing antiracist school integration, then this book may be just for you.

What I did like . . . the history and sociology, the more creative sections (poems and important phrases repeated many times), the awareness brought to the evil of segregation. I see positive reviews and I am thankful that my experience is not universal. I know that privileged white folks need to say, hey, hello, I have been hugely oblivious to my biases and here's how I'm learning to spot them and change direction. It's important and necessary. I just wish it had been done in a different way.

ETA: One more area that weighed heavily on my heart was the portrayal of the author as the emotional support of the teachers during the pandemic, and her end note that she'll see the teachers "on the field at sunset."

I attended a workshop with the late Courtney Mykytyn, founder of Integrated Schools, and she was very adamant that white parents *not* be the BFF of the teacher because that's a white parent thing. I was a teacher and goodness knows they need support, but the white parent as a texting buddy of the teacher, as a *peer* and friend, is part of white supremacy culture and further perpetuates power imbalances when that's not the expectation or position held by Black and Brown parents. If there's a wish list I quietly buy from it, but I try to maintain a professional distance from the teachers and staff.

It's all well and good to aim for self-awareness, to struggle over how to show up and how not to, but if in the end you're the PTA president and have made yourself integral to the entire staff, is it OK to perpetuate white supremacy culture patterns because people just like you so darn much?

Again, I circle back to . . . this was too much, too soon. I wish the author well on her journey. I know she has a sharp mind and open heart.

Update Dec. 2022: I met a mom recently who was inspired by this book to pull her child from private school and put them in a hyper-segregated school. So again I thought, maybe it's just me. Maybe if you haven't been introduced to the idea of not putting your child in a privileged school, this book is a good starting point.

I loved this book, it turned out to be exactly what I had hoped for and am so glad I had the opportunity to read it thanks to Netgalley and the publisher for the ARC! The author, Courtney Martin tells the story of deciding which school to enrol her oldest child, Maya, in pre-k. While some people might take this decision lightly and choose the school closest to them or the school they attended as a child, Courtney tours many schools and makes the decision with race and integration in mind. This memoir dives deep into examining the faults of the public education system, both from those working in the system, as well as the families who drive the change within their children’s education. The author gives an honest, and often humorous, commentary as she describes her interactions with students, teachers, principals, parents and community members during her daughter’s first 3 years of school. In the final chapters she also reflects on the changes the pandemic has brought to the education system, which reminds readers that tackling problems within the public education (and any efforts related to social justice) will always be a work in progress, and that no matter where your story ends, there is more work to do to make change in the future. This book is definitely a worthwhile read for any stakeholders in education, including teachers, policy makers, parents and maybe even students!

This book vulnerably gets right to the ways well-meaning White people perpetuate inequity. Martin's words perfectly expressed many of my own failures. An incredible read.