You need to sign in or sign up before continuing.

Take a photo of a barcode or cover

fast-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

No

Loveable characters:

No

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

challenging

dark

tense

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

A mix

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

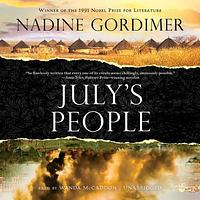

It took me a long time and some effort to get to and through this fairly slim volume, despite Gordimer being one of the last female Nobel Prize winners I hadn't read, and this book being part of the "50 Great books by African Women"-list, that I'm slowly working my way through...

The story is a thought experiment of what-if Apartheid came to an end, because the black refused to obey the white - and all power roles were reversed. Written before Apartheid ended, it was a possible future - delving into not the political implications, but the personal ones: How would this power reversal play out between the former white masters and their former man-servant / house boy. All very interesting, and interesting to explore. However the literary style makes for very slow progress and (to me anyway) hard reading. The looong descriptions of cockroaches, rags to replace menstruation pads, or the shivering of a chest between (or in the middle of) dialogues, frankly makes me want to forget about this, and complain that it would have made a good short story, if you'd cut out about a hundred pages. It might just be me, or maybe the level of detail of whites having to live the life of poor blacks in the country, and the poignant pauses in conversation would have had a greater effect before Mandela's peace and reconciliation politics changed South Africa forever?

The story is a thought experiment of what-if Apartheid came to an end, because the black refused to obey the white - and all power roles were reversed. Written before Apartheid ended, it was a possible future - delving into not the political implications, but the personal ones: How would this power reversal play out between the former white masters and their former man-servant / house boy. All very interesting, and interesting to explore. However the literary style makes for very slow progress and (to me anyway) hard reading. The looong descriptions of cockroaches, rags to replace menstruation pads, or the shivering of a chest between (or in the middle of) dialogues, frankly makes me want to forget about this, and complain that it would have made a good short story, if you'd cut out about a hundred pages. It might just be me, or maybe the level of detail of whites having to live the life of poor blacks in the country, and the poignant pauses in conversation would have had a greater effect before Mandela's peace and reconciliation politics changed South Africa forever?

challenging

tense

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

A mix

Strong character development:

No

Loveable characters:

No

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

Interesting ideas, writing got on my nerves. Entirely possible I didn’t pay close enough attention to understand everything the author was saying here.

reflective

tense

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Complicated

Loveable characters:

No

Diverse cast of characters:

No

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

In July’s People, Nadine Gordimer imagines a violent, chaotic end to South Africa’s apartheid system: all-out war between black and white, with other nations getting involved (like Russia, Cuba, the US), mainly to support their own self-interest.

July is a domestic servant who has smuggled the liberal white family he works for out of Johannesburg to stay hidden in his village, far from the danger. The book describes how the family adjusts to their new lives and uncertain future, mainly from the perspective of the white wife and mother, Maureen.

Gordimer’s insights into racism and how apartheid corrupted human relationships are astute and powerful. As the book progresses, Maureen comes to realise that all she had believed about July when he was their ‘house-boy’ was an illusion and that their relationship was almost entirely determined by the oppressive system in which they lived.

Her sense of herself as a liberal, as a good boss who is opposed to apartheid and tries to treat her staff well, is shown to be self-delusion — although Gordimer doesn’t have solutions for the question that realisation provokes in the reader: is it even possible for people from the privileged class to truly act with integrity when their entire society is based on oppression and inequality?

Perhaps for Gordimer personally, the answer lay in writing novels such as July’s People.

The book was published in 1981, around a decade before the end of apartheid, and so it was part of the building body of political, social and cultural evidence against that regime. I say social and cultural evidence because it included not just news reports on events such as the Soweto uprising, but novels, music, and blockbuster movies like Cry Freedom.

This body of evidence arguably contributed to the relatively peaceful end of regime (not the catastrophic violence that Gordimer predicted), because it created change from within, as well encouraging international pressures.

That’s why this book is important — it was part of a global push to end apartheid — but is it still relevant in 2016? For many readers, I suspect it will seem dated. These days there are many novels on racism, from the perspectives of people who’ve been on the receiving end, and there are many, many more novels by writers of African heritage, than there were in 1981.

Why read an old novel by a white author? Well, I think because her analysis of white privilege, written before that term was even in wide usage, still holds good. And it’snecessary that white people can recognise our privilege and think and talk about the implications of that. July’s People could give us white folk another nudge along the way to more self-awareness about the roles we play in perpetuating racism. Given what’s going on in Northern Territory prisons, and Australia’s offshore detention centres (not to mention the rise of trump & Brexit), Gordimer’s insights are as important as ever.

Having said that, though … white voices such as Gordimer’s should only be part of the chorus, not the lead singers. I read the book because it was the ‘July’ reading for ABC Radio National’s African Book Club. The ten books to be covered were voted for by listeners from a list of 20, but the only South African authors on the final list (Gordimer, Paton & Coetzee) are all white, famous authors of ‘classic’ novels.

I suppose this is just a reflection of Book Club readers’ desire to get across the African literary canon (the list includes Heart of Darkness and Things Fall Apart), but it’s disappointing. Why not vote for Black African writers and learn from their perspectives? Why not vote for African authors you’ve never heard of? Why not decide you want to read Black South African authors who write about apartheid and racism, or indeed, other concerns for modern South Africa? It strikes me that maybe the Book Club fans who voted white authors up that list are in the same boat as Maureen: well-meaning, liberal, but a bit self-deluded about the realities of racism.

________________________________________

In explanation of only giving the book three stars on Goodreads: I was often irritated by Gordimer’s style. Occasionally her sentences were so convoluted that they lost meaning, but more annoyingly, she used dashes to signify both speech and asides. I would get totally lost trying to figure out who said what, or if they said anything at all! It seemed overly stylised, which is a shame because the content of the novel is so important and otherwise she’s a great writer — economical, evocative, and disturbing.

July is a domestic servant who has smuggled the liberal white family he works for out of Johannesburg to stay hidden in his village, far from the danger. The book describes how the family adjusts to their new lives and uncertain future, mainly from the perspective of the white wife and mother, Maureen.

Gordimer’s insights into racism and how apartheid corrupted human relationships are astute and powerful. As the book progresses, Maureen comes to realise that all she had believed about July when he was their ‘house-boy’ was an illusion and that their relationship was almost entirely determined by the oppressive system in which they lived.

Her sense of herself as a liberal, as a good boss who is opposed to apartheid and tries to treat her staff well, is shown to be self-delusion — although Gordimer doesn’t have solutions for the question that realisation provokes in the reader: is it even possible for people from the privileged class to truly act with integrity when their entire society is based on oppression and inequality?

Perhaps for Gordimer personally, the answer lay in writing novels such as July’s People.

The book was published in 1981, around a decade before the end of apartheid, and so it was part of the building body of political, social and cultural evidence against that regime. I say social and cultural evidence because it included not just news reports on events such as the Soweto uprising, but novels, music, and blockbuster movies like Cry Freedom.

This body of evidence arguably contributed to the relatively peaceful end of regime (not the catastrophic violence that Gordimer predicted), because it created change from within, as well encouraging international pressures.

That’s why this book is important — it was part of a global push to end apartheid — but is it still relevant in 2016? For many readers, I suspect it will seem dated. These days there are many novels on racism, from the perspectives of people who’ve been on the receiving end, and there are many, many more novels by writers of African heritage, than there were in 1981.

Why read an old novel by a white author? Well, I think because her analysis of white privilege, written before that term was even in wide usage, still holds good. And it’snecessary that white people can recognise our privilege and think and talk about the implications of that. July’s People could give us white folk another nudge along the way to more self-awareness about the roles we play in perpetuating racism. Given what’s going on in Northern Territory prisons, and Australia’s offshore detention centres (not to mention the rise of trump & Brexit), Gordimer’s insights are as important as ever.

Having said that, though … white voices such as Gordimer’s should only be part of the chorus, not the lead singers. I read the book because it was the ‘July’ reading for ABC Radio National’s African Book Club. The ten books to be covered were voted for by listeners from a list of 20, but the only South African authors on the final list (Gordimer, Paton & Coetzee) are all white, famous authors of ‘classic’ novels.

I suppose this is just a reflection of Book Club readers’ desire to get across the African literary canon (the list includes Heart of Darkness and Things Fall Apart), but it’s disappointing. Why not vote for Black African writers and learn from their perspectives? Why not vote for African authors you’ve never heard of? Why not decide you want to read Black South African authors who write about apartheid and racism, or indeed, other concerns for modern South Africa? It strikes me that maybe the Book Club fans who voted white authors up that list are in the same boat as Maureen: well-meaning, liberal, but a bit self-deluded about the realities of racism.

________________________________________

In explanation of only giving the book three stars on Goodreads: I was often irritated by Gordimer’s style. Occasionally her sentences were so convoluted that they lost meaning, but more annoyingly, she used dashes to signify both speech and asides. I would get totally lost trying to figure out who said what, or if they said anything at all! It seemed overly stylised, which is a shame because the content of the novel is so important and otherwise she’s a great writer — economical, evocative, and disturbing.

Kanskje mer 2,5.

En vanskelig bok å lese; temaet er vanskelig og den er til tider kronglete skrevet. Kanskje er det den norske oversettelsen som gjør det. Var uansett bare en helt ok leseopplevelse.

En vanskelig bok å lese; temaet er vanskelig og den er til tider kronglete skrevet. Kanskje er det den norske oversettelsen som gjør det. Var uansett bare en helt ok leseopplevelse.

While reading certain books, like this one, I think of the numerous term papers that can be written from them. Nadine Gordimer's writing is concise, her ability to dissect relationships remarkable.

In this book, Gordimer envisions civil unrest after Black South Africans take up arms against the apartheid regime. July, a black servant to the Smales, a liberal white family, leads them to his rural village for safety.

Reading South African books from the days of the apartheid regime, I always feel a sense of claustrophobia. It happened with Bessie Head, it happened with J.M. Coetzee. One can literally feel the helplessness and frustrations of the characters, and it happened again with Gordimer and the characters in her book finding ways to cope with situations that are alien to them.

Through Maureen and Bamford Smale, Gordimer shows how being well meaning is fruitless in the face of systematic oppression. Having been well off and living in the suburbs of the city, they find themselves hiding in a thatched hut without the amenities they are used to and relying on the kindness of those that had been until their escape, less privileged than them.

One of the things that stuck with me from this story is how freedom for the oppressed has to go beyond sentiment. That small gestures and well meant thoughts are never enough in the face of systematic oppression.

It is only after I finished reading did I notice how well written and multidimensional the characters are. Even the minor characters that breeze in and out of the story, have been written so well, and all within 160 pages.

In this book, Gordimer envisions civil unrest after Black South Africans take up arms against the apartheid regime. July, a black servant to the Smales, a liberal white family, leads them to his rural village for safety.

Reading South African books from the days of the apartheid regime, I always feel a sense of claustrophobia. It happened with Bessie Head, it happened with J.M. Coetzee. One can literally feel the helplessness and frustrations of the characters, and it happened again with Gordimer and the characters in her book finding ways to cope with situations that are alien to them.

Through Maureen and Bamford Smale, Gordimer shows how being well meaning is fruitless in the face of systematic oppression. Having been well off and living in the suburbs of the city, they find themselves hiding in a thatched hut without the amenities they are used to and relying on the kindness of those that had been until their escape, less privileged than them.

One of the things that stuck with me from this story is how freedom for the oppressed has to go beyond sentiment. That small gestures and well meant thoughts are never enough in the face of systematic oppression.

It is only after I finished reading did I notice how well written and multidimensional the characters are. Even the minor characters that breeze in and out of the story, have been written so well, and all within 160 pages.

An incredibly sensitive, beautiful, taut and thought-provoking story set in South Africa in 1980, as the black uprisings in Soweto and Johannesburg became increasingly violent. The book follows a white family taken into the bush village of their male servant for protection, and traces the changes and insights they have into their own, and each other's, lives. Powerful.

informative

reflective

tense

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Plot

Strong character development:

No

Loveable characters:

No

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes