Take a photo of a barcode or cover

adventurous

informative

inspiring

reflective

sad

slow-paced

informative

inspiring

medium-paced

adventurous

emotional

informative

inspiring

medium-paced

informative

sad

medium-paced

Chester Nez is an inspirational man. He does not sugar coat the war or his part in it. He also does not complain about his treatment by society. He just delivers his story with a frankness that is inspiring.

I like that he shares the beliefs of his people and how those beliefs have helped him through the difficult times. He was a great man, who along with all of the code talkers, deserves are respect.

I like that he shares the beliefs of his people and how those beliefs have helped him through the difficult times. He was a great man, who along with all of the code talkers, deserves are respect.

adventurous

informative

inspiring

reflective

medium-paced

Moderate: Animal death, Child death, Racism

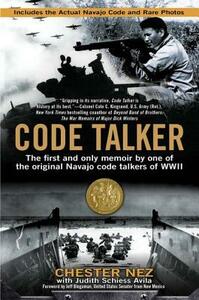

Amazing story. Chester Nez was given his name when he went to school. Bosrding school was tough and cruel in many ways. The teachers and matrons would not talk Navajo and yhe children were allowed yo spsak only English, even to each other. And when you don't understa d what someone is saying to you and have no idea what they are talking about it gets rough. Especially if you don't know they are telling you to talk another language you've never even heard! But he learns to speak English at school while continuing Navajo at home. While in high school as the US enters WW II, he heard they are wanting Navajo who can speak both English and Navajo. Out of hundreds of applicants, after testing they select 32. These original Navajo are told to devise a code for use in the Pacific that the marines hope the Japanese will not be able to break. It is a code within a code - Navajo is spoken on a radio but the words used have a double meaning. Nez is sent into the Pacific with a good friend. The code talkers are always paired, 2 to a radio. One cranks the radio yhe other takes and send messages and they swap about. But both always listen so they can be sure they are transcribing correctly. When new recruits come to tbe Pacific, the teams are split up and each given s new partner to work with so there is one experienced head with each new code talker. Thet had to overcome a lot be ause for some reason some thought they were talking Japanese to each other. Many did not know because this was top secret from the Japanese. He tells some incredible stories of the fighting because the code talkers were in the thick of it. He goes on to tell of his life after the war and the way it changed when the secret was declassified and they could talk about what they had done in the war. Until then they had not been allowed to tell anyone.

inspiring

fast-paced

Despite decades of technological advancement and entire countries' worth of money being thrown at the problem, machine translation has still not replaced the human brain. The neural networks that power Google Translate, one of the best (yes, I said best) machine translators out there, can do a pretty good job if you give them something in a language that's commonly translated to/from English—Spanish, Portuguese, or French, for example. But even then the machine doesn't "know" the languages it's using; it's only mapping one set of data points to another set of data points. And it's genuinely incapable of understanding context-dependent words: if you tell the machine to give you the French word for "read," it has no way of knowing if you want "lire" (infinitive verb), "avoir lu" (past perfect), "lisais" (imperfect indicative), "lu" (masculine singular past participle), "lus" (masculine plural past participle), "lue" (feminine singular past participle), "lues" (feminine plural past participle), "lisez" (second-person plural or formal imperative), "lis" (second-person singular imperative), or something else entirely, because there's no contextual information clarifying your request. Machines don't know what semantics are, and they sure as hell don't know anything about nuance.

Neural networks are often described as machines capable of learning, but they're not, not really—they're capable of creating new things, but only that which is formed from things they've already been given (i.e., a neutral network fed the English dictionary will not be able to understand Chinese). A neural network told to identify pictures of sheep will not understand the idea of sheep as a concept, and will instead map the word "sheep" to a certain cluster of pixels that can commonly be found in still images of sheep. This will, predictably, result in neural networks which misidentify clouds as sheep. Often, neural networks will "learn" that those clusters of pixels labelled "sheep" tend to be found in pictures of green fields, and thus you'll wind up with neural networks being given a picture of an empty pasture and confidently informing you that there's a 90% probability that there's a sheep in that picture. There's not—there never is—but the neural network can't actually distinguish between "sheep" and "location where sheep-pixels are commonly found," so you'll end up with a lot of unhelpful information.

Ever wonder why small children can so easily identify dogs, yet tend to call every unknown quadruped a dog as well? It has to do with the way our brains categorise schema. Dogs are an incredibly diverse species—a teacup chihuahua and a St. Bernard have almost nothing in common from a morphological standpoint, but thankfully phenotyping doesn't usurp genotyping when it comes to ranked taxonomy—but human brains are hardwired to recognise "dog" from a sea of potentially unfriendly similar-shaped animals. The way this works is through a process of elimination: if an unknown creature looks more like a dog than it looks like anything else, it's probably a dog. And, most of the time, it is. But machines don't have this ability, even when they can fake it pretty convincingly: they're not capable of truly, genuinely "guessing" what something is. And so a machine can always be predicted, controlled, overridden. Because the human brain, that 1.2-1.4 kg lump of meat and electricity, is capable of making shit up that's not logical. Language can't be parsed mathematically, no matter how many people try; it's organic, illogical.

And that's why linguistics are cooler than maths.No this wasn't to prove a point to anyone in particular.

Neural networks are often described as machines capable of learning, but they're not, not really—they're capable of creating new things, but only that which is formed from things they've already been given (i.e., a neutral network fed the English dictionary will not be able to understand Chinese). A neural network told to identify pictures of sheep will not understand the idea of sheep as a concept, and will instead map the word "sheep" to a certain cluster of pixels that can commonly be found in still images of sheep. This will, predictably, result in neural networks which misidentify clouds as sheep. Often, neural networks will "learn" that those clusters of pixels labelled "sheep" tend to be found in pictures of green fields, and thus you'll wind up with neural networks being given a picture of an empty pasture and confidently informing you that there's a 90% probability that there's a sheep in that picture. There's not—there never is—but the neural network can't actually distinguish between "sheep" and "location where sheep-pixels are commonly found," so you'll end up with a lot of unhelpful information.

Ever wonder why small children can so easily identify dogs, yet tend to call every unknown quadruped a dog as well? It has to do with the way our brains categorise schema. Dogs are an incredibly diverse species—a teacup chihuahua and a St. Bernard have almost nothing in common from a morphological standpoint, but thankfully phenotyping doesn't usurp genotyping when it comes to ranked taxonomy—but human brains are hardwired to recognise "dog" from a sea of potentially unfriendly similar-shaped animals. The way this works is through a process of elimination: if an unknown creature looks more like a dog than it looks like anything else, it's probably a dog. And, most of the time, it is. But machines don't have this ability, even when they can fake it pretty convincingly: they're not capable of truly, genuinely "guessing" what something is. And so a machine can always be predicted, controlled, overridden. Because the human brain, that 1.2-1.4 kg lump of meat and electricity, is capable of making shit up that's not logical. Language can't be parsed mathematically, no matter how many people try; it's organic, illogical.

And that's why linguistics are cooler than maths.

emotional

informative

inspiring

reflective

medium-paced