Take a photo of a barcode or cover

This novel is like literary Photorealism, with paragraph-long descriptions of meals and their serving dishes, women's clothing, and even the street-fighting of the Revolution of 1848. Like Balzac when he's serious, Flaubert skewers the idle rich, romantic youth, and French society in general. It is a very long book and perhaps its past its relevance, despite James Wood's assertion that all modern writers owe Flaubert a debt for his naturalism.

Esse Flaubert não me instigou como o fizera o Bovary, é um grande libelo da educação sentimental de um rapaz na Paris do século XIX, certamente com vernizes autobiográficos de Flaubert, não sei se me tornei demasiado cínica, mas essa história de amor platônico para toda a vida caiu-me como um balde de água fria... Devo sentir-me mal a julgar que minhas paixões não duram mais que um ano? Rá! Corta essa Flaubert!

I picked this up almost at random. It had been sitting on a shelf for over a year, I loved “Madame Bovary”, and I like to throw a classic into my reading mix regularly.

This book ripped me apart. When I was sleeping I wanted to keep reading it, when I was reading it I wanted to be reading faster. And then as I neared the end, I slowed down and hoped it would never end.

Perfection overflows here!!!

Part Three, Chapter Six is devastating. The final chapter, melancholic!

The type of novel that inspires the writer and the reader.

This book ripped me apart. When I was sleeping I wanted to keep reading it, when I was reading it I wanted to be reading faster. And then as I neared the end, I slowed down and hoped it would never end.

Perfection overflows here!!!

Part Three, Chapter Six is devastating. The final chapter, melancholic!

The type of novel that inspires the writer and the reader.

challenging

reflective

tense

slow-paced

A fine book for and about self-pitying young men who romanticize women all out of proportion.

See: "She looked like the women in romantic novels. He would not have wanted to add anything to her appearance, or to take anything away. His world had suddenly grown bigger. She was the point of light on which all things converged; and lulled by the movement of the carraige, his eyelids half closed, his gaze directed at the clouds, he gave himself up to an infinite, dreamy joy."

Also: "He knew the shape of each of her nails; he delighted in listening to the rustle of her silk dress when she passed a door; he furtively sniffed at the scent on her handkerchief; her comb, her gloves, her rings were things of special significance to him, as important as works of art, almost endowed with life like human beings."

Or: "Looking at this woman had an enervating effect on him, like a scent that is too strong. The sensation penetrated to the very depths of his being, and became almost a habitual condition, a new mode of existence."

And so on and so forth.

See: "She looked like the women in romantic novels. He would not have wanted to add anything to her appearance, or to take anything away. His world had suddenly grown bigger. She was the point of light on which all things converged; and lulled by the movement of the carraige, his eyelids half closed, his gaze directed at the clouds, he gave himself up to an infinite, dreamy joy."

Also: "He knew the shape of each of her nails; he delighted in listening to the rustle of her silk dress when she passed a door; he furtively sniffed at the scent on her handkerchief; her comb, her gloves, her rings were things of special significance to him, as important as works of art, almost endowed with life like human beings."

Or: "Looking at this woman had an enervating effect on him, like a scent that is too strong. The sensation penetrated to the very depths of his being, and became almost a habitual condition, a new mode of existence."

And so on and so forth.

I read this because I'm pretending I will write an essay collection by the same title. There were moments of lovely language and some humor but overall it was a bit of a slog. The main character is annoying--selfish, self-centered, and just kind of absurd. It is interesting how it is a book about class/revolution as well as about matters of romantic entanglements. I'm not sure I find the balance convincing. Overall, not my favorite but feels good to have my homework done.

Kindle translation not terribly brilliant. Some of language nuance lost in translation. As a A portrait of lassitude in mid 19th century France it is peerless. Flaubert had a real feel for the indolence of the waning petit aristocracy.

Tinha ficado algo apreensivo aquando da minha resenha de “Madame Bovary” (1856), mas aceitei que o problema fosse meu. Assumi que a obra tinha surgido numa fase embrionária do realismo na literatura, que tinha obrigado Flaubert a inovar e a abrir caminhos sem pauta para se orientar, e que por isso teria de ser condescendente por estar a quase dois séculos de distância. Mas ao chegar ao final de “A Educação Sentimental”, esta minha abordagem já não serve, porque passados 15 anos, Flaubert não alterou em nada os problemas que eu tinha sentido face a "Madame Bovary".

Só em parte consigo entender que Proust e Kafka se tenham deliciado com Flaubert. Sim a escrita tem momentos muito bons, existe uma organização frásica muito boa, capaz de gerar bom ritmo, de adocicar a leitura, a ponto de fazer toda a experiência fluir muito naturalmente. Por outro lado, e agora no final destes dois livros, percebo que Flaubert terá sido um indivíduo com problemas obsessivos, centrado sobre si e sobre a sua arte, incapaz de lidar com o social. E é por isso que apesar de eu não ver proximidade temática, entre Proust e Kafka com Flaubert, eles por sentirem problemas ao nível dos de Flaubert, terão lido nas entrelinhas. Mas fosse apenas este o meu problema com a obra, e aceitaria Flaubert sem problemas, o problema é que ao contrário deles, Flaubert não foi capaz de criar uma obra autónoma.

Ou seja, “Madame Bovary” e “Educação Sentimental”, seguem ambos a mesma formula, com uma variação apenas, num temos uma mulher, no outro um homem. Isto parece ridículo, mas foi exatamente isto que senti no final dos dois livros. **** SPOILER **** Temos dois personagens, Emma e Frederic, ambos apenas centrados sobre si, nos seus amores, totalmente insensíveis à restante sociedade, desde a própria família, aos amigos, até mesmo aos próprios filhos. E se já me tinha chocado com o desenho da relação entre Emma e a sua filha Berthe, Frederic vai muito mais longe, roçando o desumano. Ter um filho e não querer saber, podemos até aceitar que se trata de alguém apenas focado em si, mas ver o filho morrer nos braços, e estar apenas preocupado com o facto da amada ir partir para outra cidade, é tão aberrante que não tenho palavras para descrever **** FIM ***.

Acabei por ter de ir confirmar que Flaubert nunca casou, nem nunca teve filhos, e para além disso, afirmava ser "antinatalista", já que considerava não querer "transmitir a ninguém os agravos e as desgraças da existência”. Lido assim, parece profundo, apesar de ser aquilo que quase todas as pessoas que conheço, e que não querem ter filhos, dizem. O problema, é que para alguém supostamente tão reflexivo sobre a existência humana, escreveu dois livros, os que li, de uma superficialidade atroz. Tanto Emma como Fréderic vivem as suas vidas sem pensar em absolutamente mais nada nem ninguém, a não ser nos seus amores, nos seus desejos, na sua própria felicidade. Como se para viver bastasse apenas amar alguém, isto claro desde que caísse na conta uma renda mensal para não ter que trabalhar e poder viver apenas a pensar no tal amor.

Flaubert criticou "Os Miseráveis" de Victor Hugo por ser um romance condescendente para com todas as classes da sociedade, pois fez bem, já que acabou a fazer o oposto. Aliás, quem tinha razão era mesmo Henry James, a quem Flaubert não conseguiu enganar:

"Aqui, a forma e o método são os mesmos que em "Madame Bovary"; a competência estudada, a ciência, e a acumulação de material, são ainda mais impressionantes; mas o livro, esse numa única palavra, está morto." (Henry James)

Como se isto não bastasse, o livro apresenta vários problemas de organização da ação e dos personagens, que fazem com que não poucas vezes as cenas não apresentem ligação entre si, ou não seja possível compreender totalmente o que o autor pretende ao colocar os personagens a dizerem certas coisas. Isto é mais um problema de edição, mas acredito que Flaubert com todas as suas idiossincrasias, tenha impedido que esse trabalho fosse feito sem o seu total controlo, e por isso o livro que temos é o que ele terá permitido que tivéssemos.

Dito tudo isto. Não dou por perdido o tempo que gastei a ler “Madame Bovary”, já “A Educação Sentimental” dispensava.

Publicado no VI em: https://virtual-illusion.blogspot.pt/2018/02/a-educacao-sentimental-1869.html

Só em parte consigo entender que Proust e Kafka se tenham deliciado com Flaubert. Sim a escrita tem momentos muito bons, existe uma organização frásica muito boa, capaz de gerar bom ritmo, de adocicar a leitura, a ponto de fazer toda a experiência fluir muito naturalmente. Por outro lado, e agora no final destes dois livros, percebo que Flaubert terá sido um indivíduo com problemas obsessivos, centrado sobre si e sobre a sua arte, incapaz de lidar com o social. E é por isso que apesar de eu não ver proximidade temática, entre Proust e Kafka com Flaubert, eles por sentirem problemas ao nível dos de Flaubert, terão lido nas entrelinhas. Mas fosse apenas este o meu problema com a obra, e aceitaria Flaubert sem problemas, o problema é que ao contrário deles, Flaubert não foi capaz de criar uma obra autónoma.

Ou seja, “Madame Bovary” e “Educação Sentimental”, seguem ambos a mesma formula, com uma variação apenas, num temos uma mulher, no outro um homem. Isto parece ridículo, mas foi exatamente isto que senti no final dos dois livros. **** SPOILER **** Temos dois personagens, Emma e Frederic, ambos apenas centrados sobre si, nos seus amores, totalmente insensíveis à restante sociedade, desde a própria família, aos amigos, até mesmo aos próprios filhos. E se já me tinha chocado com o desenho da relação entre Emma e a sua filha Berthe, Frederic vai muito mais longe, roçando o desumano. Ter um filho e não querer saber, podemos até aceitar que se trata de alguém apenas focado em si, mas ver o filho morrer nos braços, e estar apenas preocupado com o facto da amada ir partir para outra cidade, é tão aberrante que não tenho palavras para descrever **** FIM ***.

Acabei por ter de ir confirmar que Flaubert nunca casou, nem nunca teve filhos, e para além disso, afirmava ser "antinatalista", já que considerava não querer "transmitir a ninguém os agravos e as desgraças da existência”. Lido assim, parece profundo, apesar de ser aquilo que quase todas as pessoas que conheço, e que não querem ter filhos, dizem. O problema, é que para alguém supostamente tão reflexivo sobre a existência humana, escreveu dois livros, os que li, de uma superficialidade atroz. Tanto Emma como Fréderic vivem as suas vidas sem pensar em absolutamente mais nada nem ninguém, a não ser nos seus amores, nos seus desejos, na sua própria felicidade. Como se para viver bastasse apenas amar alguém, isto claro desde que caísse na conta uma renda mensal para não ter que trabalhar e poder viver apenas a pensar no tal amor.

Flaubert criticou "Os Miseráveis" de Victor Hugo por ser um romance condescendente para com todas as classes da sociedade, pois fez bem, já que acabou a fazer o oposto. Aliás, quem tinha razão era mesmo Henry James, a quem Flaubert não conseguiu enganar:

"Aqui, a forma e o método são os mesmos que em "Madame Bovary"; a competência estudada, a ciência, e a acumulação de material, são ainda mais impressionantes; mas o livro, esse numa única palavra, está morto." (Henry James)

Como se isto não bastasse, o livro apresenta vários problemas de organização da ação e dos personagens, que fazem com que não poucas vezes as cenas não apresentem ligação entre si, ou não seja possível compreender totalmente o que o autor pretende ao colocar os personagens a dizerem certas coisas. Isto é mais um problema de edição, mas acredito que Flaubert com todas as suas idiossincrasias, tenha impedido que esse trabalho fosse feito sem o seu total controlo, e por isso o livro que temos é o que ele terá permitido que tivéssemos.

Dito tudo isto. Não dou por perdido o tempo que gastei a ler “Madame Bovary”, já “A Educação Sentimental” dispensava.

Publicado no VI em: https://virtual-illusion.blogspot.pt/2018/02/a-educacao-sentimental-1869.html

As the French President announces major Covid 19 restriction measures today, I was reminded of this book from a time when restrictions and curfews were the norm but for very different reasons...

[b:L'éducation sentimentale|1420825|L'Éducation sentimentale|Gustave Flaubert|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1356152703l/1420825._SY75_.jpg|314156] is set in the 1840s, and the political upheavals of those years are referenced constantly—though they don't impinge as much as they might on the main character, Frédéric Moreau. Frédéric is a law student who'd like to be a writer, but he doesn't find it easy to study or write, so he leads the typical student life, sleeping, eating and drinking—and enjoying the cartoons in the Charivari newspaper: Frédéric avala un verre de rhum, puis un verre de kirsch, puis un verre de curaçao, puis différents grogs, tant froids que chauds. Il lut tout le journal, et le relut; il examina, jusque dans les grains du papier, la caricature du Charivari; à la fin, il savait par coeur les annonces.

But while Frédéric spends time examining every detail of the cartoons and the advertisments in the Charivari, his friends are variously involved in preparing the revolt which will eventually depose King Louis Philippe in 1848. Frédéric is not a revolutionary himself, in fact he's not sure what he is yet. His male friends don't know either and they constantly pull him in different directions in an effort to find out.

Fréderic has women friends too, and one of them sounds a lot like [b:Madame Bovary|60694|Madame Bovary|Gustave Flaubert|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1389645518l/60694._SY75_.jpg|2766347], from the top of her dark tresses which 'lovingly framed her ovale face’ to the toe of her little boot. This Madame Bovary look-alike is called Madame Arnoux, and she gradually becomes the key love interest in Fréderic’s life, though she keeps herself in the background of the story. And although she's a very faithful spouse to M. Arnoux, she reminded me of Emma Bovary every time she swayed into a scene, especially when it was a question of her 'bottines'; Flaubert and Frédéric seem to have a thing about slim leather-clad feet peeping out from underneath the vastness of a crinoline. And since Frédéric had been studying the caricatures in the Charivari so closely, I began studying them too, especially the ones by Honoré Daumier, and stumbled on many parallels between Flaubert’s scenarios and Daumier's sketches.

When Frédéric accompanies Madame Arnoux on her shopping trips, it’s hard not to imagine the scene like this, especially since Frédéric is such a very flexible character:

(The text underneath Daumier's sketch says that since women now wear skirts made of steel, men would need to be made of rubber to give them their arm in the street!)

Daumier intends to be funny of course, and you might argue that Flaubert is being serious much of the time. But even when Flaubert is describing something potentially sedate or serious, he makes me laugh. So when I came on this description of the kind of elaborate curtsies people make in polite society, I couldn't help matching the passage with another Daumier cartoon: Les invités arrivaient; en manière de salut, ils jetaient leur torse de côté, ou se courbaient en deux, ou baissaient la figure seulement

Sometimes, I was convinced that Flaubert himself had been studying Daumier's cartoons before writing certain scenes because they just match together so well. One of Frédéric's least bright friends tries his hand at a witty remark about a French writer called La Bruyère, known for his book 'Les Caractères', while passing a plate of grouse (coq de bruyère) to his friends at table: il tenta même un calembour, car il dit, comme on passait un coq de bruyère, "Voilà le meilleur des caractères de bruyère"!

And of course, Daumier just happens to have a witty cartoon about a grouse too:

At the same dinner, the Wit insults one of Frédéric's women friends, and next thing he knows, Frédéric is involved in a duel—one of the funniest scenes in the book. As the duel is about to begin, someone runs up to shout stop, and the Wit, thinking it’s the police, faints in fear and scratches his thumb whereupon the duel is abandoned because blood has been spilled.

Has Daumier such a scene? But of course!

The more I looked for correspondences between Flaubert's and Daumier's scenes, the more I found. Take this one for example, where Fréderic spots a crowd in front of a painting of a young woman he has become slightly involved with and discovers that the painting has his own name under it, F Moreau—as the owner, of both the painting and the lady, it is implied! And he's not even Rosanette's lover as yet! Complications seem to follow him about!

Daumier just happens to have a drawing of some people in front of a painting of a young woman too - and the name ‘Moreau’ is associated with it:

But it's Gustave Moreau’s Sphinx,

about which the pair in the cartoon are having a conversation: "Un chat décolleté avec une tête de femme, ça s'appelle donc un Sphinx?" "Certainement…en grec!" ("So a bare-breasted cat with a woman's head is called a Sphinx?" asks the man with the catalogue. "Certainly," says the woman, "- in Greek!" (clearly she doesn't want to think such creatures can exist in French))

Meantime, in spite of his complicated love life, Frédéric continues to sit over the dinner table discussing the state of the nation with some smug characters: Cependant, objecta M, la misère existe, avouons-le! Mais le remède ne dépend ni de la Science ni du Pouvoir. C'est une question purement individuelle. Quand les basses classes voudront se débarrasser de leurs vices, elles s'affranchiront de leurs besoins. Que le peuple soit plus moral, et il sera moins pauvre!

Daumier was obviously at the same dinner!

The summer of 1848 arrives, and Frédéric hasn't passed his bar exams, he hasn't written the book he planned to write, and he hasn't got involved in the Reform movement. One of his friends turns up with the news that the time has finally come to remove King Louis Philippe from power, and he strongly urges Frédéric to join the fight to topple the 'poire': Mon vieux, La poire est mûre. Selon ta promesse, nous comptons sur toi. On se réunit demain au petit jour, place du Panthéon. Entre au café Soufflot. Il faut que je te parle avant la manifestation.

Daumier has some great caricatures of Louis Philippe as the 'poire', ripe for harvesting:

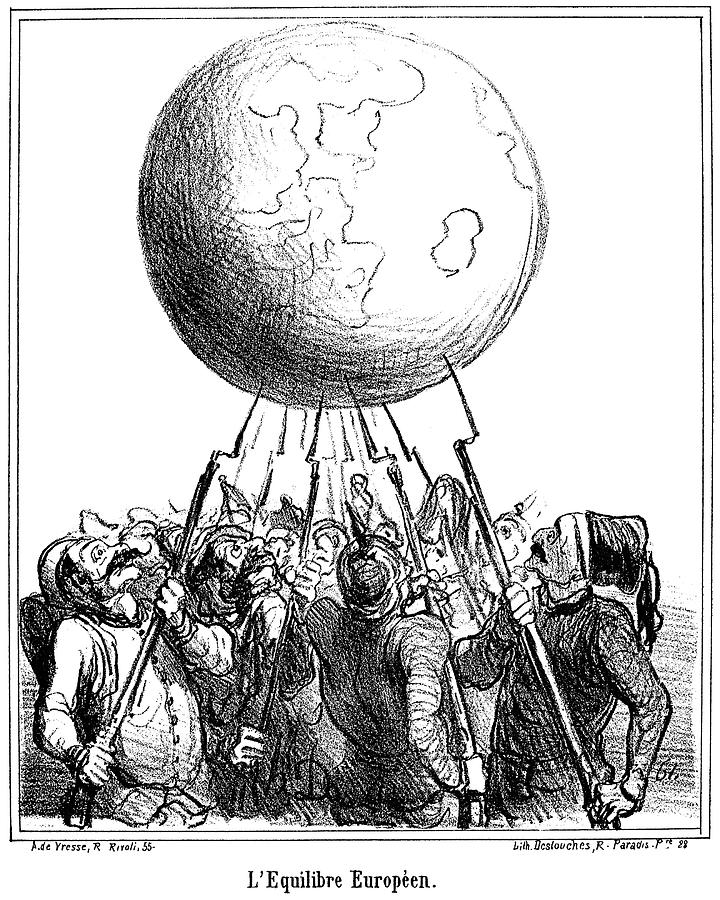

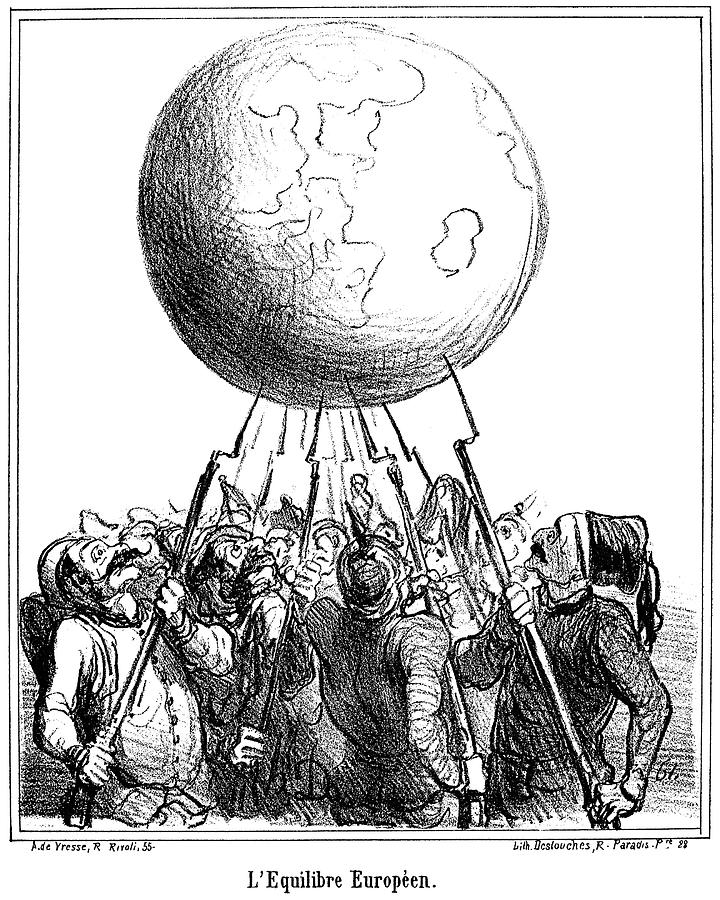

So Paris is in uproar and people are on the barricades:

But where is Frédéric? Did he answer the call?

Hmm, he has his own way of addressing Reform. He decides to stop shilly-shallying and to finally sleep with Rosanette (his passion for Mme Arnoux being still unconsummated): Mille pardons ! » dit Frédéric, en lui saisissant la taille dans les deux mains. -« Comment ? que fais-tu ?» balbutia Rosanette. Il répondit : -« Je suis la mode, je me réforme. » Elle se laissa renverser sur le divan, et continuait à rire sous ses baisers.

Later Frédéric's conscience wakes up and he becomes concerned for his comrades. He searches for them in the Palace which the People have invaded, and comes on a crazy scene in which a group of people try out the throne for size:

ils arrivèrent dans la salle des Maréchaux. Les portraits de ces illustres, sauf celui de Bugeaud percé au ventre, étaient tous intacts..Sur le trône était assis un prolétaire à barbe noire, la chemise entrouverte, l'air hilare et stupide comme un magot. D'autres gravissaient l'estrade pour s'asseoir à sa place.

Then for twenty pages, while Paris rumbles explosively, Flaubert sends Fréderic and Rosanette on a sightseeing holiday to Fontainebleau, visiting the Chateau which was the country residence of many former kings—like the most carefree of tourists (allowing Flaubert to offer us fine descriptive passages), while back in Paris, the world as they knew it is balancing on the tip of a bayonet.

But of course Flaubert isn’t ignoring the troubles in Paris at all, just showing us how good he is at metaphor : des chênes rugueux, énormes, qui se convulsaient..s'étreignaient les uns les autres, et fermes sur leurs troncs, pareils à des torses, se lançaient avec leurs bras nus des appels de désespoir, des menaces furibondes..immobilisés dans leur colère

While reading that description of an oak wood near the Chateau, in which the enormous trees surge and sway like a seething mass of angry beings, we can’t but think immediately of the confrontations between the people and the monarchy during the uprisings, as in this sketch by Daumier of the Peasant’s Revolt:

A little further on, Flaubert describes a granite quarry in terms that make it resemble a long-forgotten ruined city, a Sodom and Gomorrah:

Un bruit de fer, des coups drus et nombreux sonnaient: c'était, au flanc d'une colline, une compagnie de carriers battant les roches. Elles se multipliaient de plus en plus, et finissaient par emplir tout le paysage, cubiques comme des maisons, plates comme des dalles, s'étayant, se surplombant, se confondant, telles que les ruines méconnaissables et monstrueuses de quelque cité disparue

Daumier has just such a scene, which he calls Paris in Revolt or Sodom and Gomorrah:

Frédéric eventually returns to the city, and the city eventually returns to a semblance of order, though no political group gets quite what they sought, and crazy compromises are made, with bankers getting into bed with socialists. Frédéric’s life is equally complicated. He's involved with four different women so he has to make constant compromises. One compromise he's faced with is marrying a rich widow: Frédéric baissait la voix, en se penchant vers son visage..Mme D ferma les yeux, et il fut surpris par la facilité de sa victoire. Les grands arbres du jardin qui frissonnaient mollement s'arrêtèrent...et il y eut comme une suspension universelle des choses.

But similarly to the political scene where temporary allies were constantly breaking their promises and betraying one another, and betraying the spirit of Liberty at the same time, Fredéric finds himself breaking his promises and betraying all the women in his life: Bientôt ces mensonges le divertirent; il répétait à l'une le serment qu'il venait de faire à l'autre, leur envoyait deux bouquets semblables, leur écrivait en même temps, puis établissait entre elles des comparaisons; - il y en avait une troisième toujours présente à sa pensée…

And just as you might be tempted to wonder what had become of the spirit of Liberty in the Paris of the day, you might also wonder what had become of Frédéric’s first love, Mme Arnoux. Well, like Liberty, she does turn up—when least expected:

The Reform movements may not welcome the ghost of Liberty, but Frédéric is glad to see Mme Arnoux, though she's a bit of a ghost of her former self. Still, their meeting towards the end of the book provides a sweet scene in which the two finally admit their deep love for each other:

elle lui dit «Quelquefois, vos paroles me reviennent comme un écho lointain, comme le son d'une cloche apporté par le vent; et il me semble que vous êtes là, quand je lis des passages d'amour dans les livres.»

«Tout ce qu'on y blâme d'exagéré, vous me l'avez fait ressentir», dit Frédéric. «Je comprends Werther, que ne dégoûtent pas les tartines de Charlotte».

In a scene which starts out very movingly, Frédéric somehow ends up drawing a parallel between his love for Mme Arnoux and the ridiculous quantities of bread and jam that Werther’s great love Charlotte was constantly preparing for her little brothers and sisters, which convinces me that Flaubert was always ready to see the ridiculous side of life, and that he shared Daumier’s view, as demonstrated in this cartoon, that life, love and lunacy might be more closely linked than we admit:

According to Flaubert's account, it did seem as if a lot of time was spent howling at the moon during those decades!

………………………………………………

I’m hoping that Flaubert’s sense of fun would have prevented him from objecting to me using illustrations in this review—though he never allowed any of his books to be illustrated in his lifetime...

[b:L'éducation sentimentale|1420825|L'Éducation sentimentale|Gustave Flaubert|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1356152703l/1420825._SY75_.jpg|314156] is set in the 1840s, and the political upheavals of those years are referenced constantly—though they don't impinge as much as they might on the main character, Frédéric Moreau. Frédéric is a law student who'd like to be a writer, but he doesn't find it easy to study or write, so he leads the typical student life, sleeping, eating and drinking—and enjoying the cartoons in the Charivari newspaper: Frédéric avala un verre de rhum, puis un verre de kirsch, puis un verre de curaçao, puis différents grogs, tant froids que chauds. Il lut tout le journal, et le relut; il examina, jusque dans les grains du papier, la caricature du Charivari; à la fin, il savait par coeur les annonces.

But while Frédéric spends time examining every detail of the cartoons and the advertisments in the Charivari, his friends are variously involved in preparing the revolt which will eventually depose King Louis Philippe in 1848. Frédéric is not a revolutionary himself, in fact he's not sure what he is yet. His male friends don't know either and they constantly pull him in different directions in an effort to find out.

Fréderic has women friends too, and one of them sounds a lot like [b:Madame Bovary|60694|Madame Bovary|Gustave Flaubert|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1389645518l/60694._SY75_.jpg|2766347], from the top of her dark tresses which 'lovingly framed her ovale face’ to the toe of her little boot. This Madame Bovary look-alike is called Madame Arnoux, and she gradually becomes the key love interest in Fréderic’s life, though she keeps herself in the background of the story. And although she's a very faithful spouse to M. Arnoux, she reminded me of Emma Bovary every time she swayed into a scene, especially when it was a question of her 'bottines'; Flaubert and Frédéric seem to have a thing about slim leather-clad feet peeping out from underneath the vastness of a crinoline. And since Frédéric had been studying the caricatures in the Charivari so closely, I began studying them too, especially the ones by Honoré Daumier, and stumbled on many parallels between Flaubert’s scenarios and Daumier's sketches.

When Frédéric accompanies Madame Arnoux on her shopping trips, it’s hard not to imagine the scene like this, especially since Frédéric is such a very flexible character:

(The text underneath Daumier's sketch says that since women now wear skirts made of steel, men would need to be made of rubber to give them their arm in the street!)

Daumier intends to be funny of course, and you might argue that Flaubert is being serious much of the time. But even when Flaubert is describing something potentially sedate or serious, he makes me laugh. So when I came on this description of the kind of elaborate curtsies people make in polite society, I couldn't help matching the passage with another Daumier cartoon: Les invités arrivaient; en manière de salut, ils jetaient leur torse de côté, ou se courbaient en deux, ou baissaient la figure seulement

Sometimes, I was convinced that Flaubert himself had been studying Daumier's cartoons before writing certain scenes because they just match together so well. One of Frédéric's least bright friends tries his hand at a witty remark about a French writer called La Bruyère, known for his book 'Les Caractères', while passing a plate of grouse (coq de bruyère) to his friends at table: il tenta même un calembour, car il dit, comme on passait un coq de bruyère, "Voilà le meilleur des caractères de bruyère"!

And of course, Daumier just happens to have a witty cartoon about a grouse too:

At the same dinner, the Wit insults one of Frédéric's women friends, and next thing he knows, Frédéric is involved in a duel—one of the funniest scenes in the book. As the duel is about to begin, someone runs up to shout stop, and the Wit, thinking it’s the police, faints in fear and scratches his thumb whereupon the duel is abandoned because blood has been spilled.

Has Daumier such a scene? But of course!

The more I looked for correspondences between Flaubert's and Daumier's scenes, the more I found. Take this one for example, where Fréderic spots a crowd in front of a painting of a young woman he has become slightly involved with and discovers that the painting has his own name under it, F Moreau—as the owner, of both the painting and the lady, it is implied! And he's not even Rosanette's lover as yet! Complications seem to follow him about!

Daumier just happens to have a drawing of some people in front of a painting of a young woman too - and the name ‘Moreau’ is associated with it:

But it's Gustave Moreau’s Sphinx,

Spoiler

about which the pair in the cartoon are having a conversation: "Un chat décolleté avec une tête de femme, ça s'appelle donc un Sphinx?" "Certainement…en grec!" ("So a bare-breasted cat with a woman's head is called a Sphinx?" asks the man with the catalogue. "Certainly," says the woman, "- in Greek!" (clearly she doesn't want to think such creatures can exist in French))

Meantime, in spite of his complicated love life, Frédéric continues to sit over the dinner table discussing the state of the nation with some smug characters: Cependant, objecta M, la misère existe, avouons-le! Mais le remède ne dépend ni de la Science ni du Pouvoir. C'est une question purement individuelle. Quand les basses classes voudront se débarrasser de leurs vices, elles s'affranchiront de leurs besoins. Que le peuple soit plus moral, et il sera moins pauvre!

Daumier was obviously at the same dinner!

The summer of 1848 arrives, and Frédéric hasn't passed his bar exams, he hasn't written the book he planned to write, and he hasn't got involved in the Reform movement. One of his friends turns up with the news that the time has finally come to remove King Louis Philippe from power, and he strongly urges Frédéric to join the fight to topple the 'poire': Mon vieux, La poire est mûre. Selon ta promesse, nous comptons sur toi. On se réunit demain au petit jour, place du Panthéon. Entre au café Soufflot. Il faut que je te parle avant la manifestation.

Daumier has some great caricatures of Louis Philippe as the 'poire', ripe for harvesting:

So Paris is in uproar and people are on the barricades:

But where is Frédéric? Did he answer the call?

Hmm, he has his own way of addressing Reform. He decides to stop shilly-shallying and to finally sleep with Rosanette (his passion for Mme Arnoux being still unconsummated): Mille pardons ! » dit Frédéric, en lui saisissant la taille dans les deux mains. -« Comment ? que fais-tu ?» balbutia Rosanette. Il répondit : -« Je suis la mode, je me réforme. » Elle se laissa renverser sur le divan, et continuait à rire sous ses baisers.

Later Frédéric's conscience wakes up and he becomes concerned for his comrades. He searches for them in the Palace which the People have invaded, and comes on a crazy scene in which a group of people try out the throne for size:

ils arrivèrent dans la salle des Maréchaux. Les portraits de ces illustres, sauf celui de Bugeaud percé au ventre, étaient tous intacts..Sur le trône était assis un prolétaire à barbe noire, la chemise entrouverte, l'air hilare et stupide comme un magot. D'autres gravissaient l'estrade pour s'asseoir à sa place.

Then for twenty pages, while Paris rumbles explosively, Flaubert sends Fréderic and Rosanette on a sightseeing holiday to Fontainebleau, visiting the Chateau which was the country residence of many former kings—like the most carefree of tourists (allowing Flaubert to offer us fine descriptive passages), while back in Paris, the world as they knew it is balancing on the tip of a bayonet.

But of course Flaubert isn’t ignoring the troubles in Paris at all, just showing us how good he is at metaphor : des chênes rugueux, énormes, qui se convulsaient..s'étreignaient les uns les autres, et fermes sur leurs troncs, pareils à des torses, se lançaient avec leurs bras nus des appels de désespoir, des menaces furibondes..immobilisés dans leur colère

While reading that description of an oak wood near the Chateau, in which the enormous trees surge and sway like a seething mass of angry beings, we can’t but think immediately of the confrontations between the people and the monarchy during the uprisings, as in this sketch by Daumier of the Peasant’s Revolt:

A little further on, Flaubert describes a granite quarry in terms that make it resemble a long-forgotten ruined city, a Sodom and Gomorrah:

Un bruit de fer, des coups drus et nombreux sonnaient: c'était, au flanc d'une colline, une compagnie de carriers battant les roches. Elles se multipliaient de plus en plus, et finissaient par emplir tout le paysage, cubiques comme des maisons, plates comme des dalles, s'étayant, se surplombant, se confondant, telles que les ruines méconnaissables et monstrueuses de quelque cité disparue

Daumier has just such a scene, which he calls Paris in Revolt or Sodom and Gomorrah:

Frédéric eventually returns to the city, and the city eventually returns to a semblance of order, though no political group gets quite what they sought, and crazy compromises are made, with bankers getting into bed with socialists. Frédéric’s life is equally complicated. He's involved with four different women so he has to make constant compromises. One compromise he's faced with is marrying a rich widow: Frédéric baissait la voix, en se penchant vers son visage..Mme D ferma les yeux, et il fut surpris par la facilité de sa victoire. Les grands arbres du jardin qui frissonnaient mollement s'arrêtèrent...et il y eut comme une suspension universelle des choses.

But similarly to the political scene where temporary allies were constantly breaking their promises and betraying one another, and betraying the spirit of Liberty at the same time, Fredéric finds himself breaking his promises and betraying all the women in his life: Bientôt ces mensonges le divertirent; il répétait à l'une le serment qu'il venait de faire à l'autre, leur envoyait deux bouquets semblables, leur écrivait en même temps, puis établissait entre elles des comparaisons; - il y en avait une troisième toujours présente à sa pensée…

And just as you might be tempted to wonder what had become of the spirit of Liberty in the Paris of the day, you might also wonder what had become of Frédéric’s first love, Mme Arnoux. Well, like Liberty, she does turn up—when least expected:

The Reform movements may not welcome the ghost of Liberty, but Frédéric is glad to see Mme Arnoux, though she's a bit of a ghost of her former self. Still, their meeting towards the end of the book provides a sweet scene in which the two finally admit their deep love for each other:

elle lui dit «Quelquefois, vos paroles me reviennent comme un écho lointain, comme le son d'une cloche apporté par le vent; et il me semble que vous êtes là, quand je lis des passages d'amour dans les livres.»

«Tout ce qu'on y blâme d'exagéré, vous me l'avez fait ressentir», dit Frédéric. «Je comprends Werther, que ne dégoûtent pas les tartines de Charlotte».

In a scene which starts out very movingly, Frédéric somehow ends up drawing a parallel between his love for Mme Arnoux and the ridiculous quantities of bread and jam that Werther’s great love Charlotte was constantly preparing for her little brothers and sisters, which convinces me that Flaubert was always ready to see the ridiculous side of life, and that he shared Daumier’s view, as demonstrated in this cartoon, that life, love and lunacy might be more closely linked than we admit:

According to Flaubert's account, it did seem as if a lot of time was spent howling at the moon during those decades!

………………………………………………

I’m hoping that Flaubert’s sense of fun would have prevented him from objecting to me using illustrations in this review—though he never allowed any of his books to be illustrated in his lifetime...

I read this in French. Stylistically a very sober and accurate portrait of the revolutionary climate, mid 19th century. Ingeniously composed. Actually it is more of a "Bildungsroman", but then one about a failed youth. Very negative outlook on life.