Take a photo of a barcode or cover

A review by ilse

A Change of Time by Ida Jessen

5.0

I feel like a person standing in a landscape so empty and open that it matters not a bit in which direction I choose to go. There would be no difference: north, south, east or west, it would be the same wherever I went.

Thyregod, Denmark at the beginning of the 20th Century. Through diary entries, Ida Jessen conveys the life of a schoolteacher, Lilly Høy, starting with recounts of her visits to her husband Vigand Bagge who is in the hospital in another town, over her response to his death and her attempts to build herself a new life, find herself a new place and identity in the rural community she is living in and find attachment to her life again.

Slowly, as Lilly through subtle allusions, flashbacks, encounters and meaningful silences discloses her past, Lilly’s life turns out to have been far less conventional than one would have expected for a woman living at that time in such a remote rural place. Before she came to live in Thyregod where she met her husband, Lilly was a vivid and intelligent student, who moved to the rural village to put her ideals as a teacher into practise. Contemplating on the past and the present now she is alone, she reflects on her relationship with Vigand, her spouse for 22 years, who was a district physician ‘for fourteen impoverished and far-flung parishes’ – a stern, taciturn, stoic man, thirty years her elder and emotionally aloof – painting a portrait of their marriage in which tiny anecdotes and moments illustrate their inability to connect, revealing Lilly’s struggle with finding a way to live together with her husband, from her angling for a tender word or a caress to her walking on eggshells not to speak a word that would lead to more marital scorn.

Can one ask a person to show that they love you? Reason, that most faithful onlooker to the tribulations of others, says no.

But what says unreason?

There is the mourning for the person her husband was, but also the grieving for the lost life, the grieving for the lost self, a confrontation with the sacrifices made, the self-repression. The voice and thoughts of the one she has lived together with for such a long time continue to resonate in her own thoughts and acts, tending to censure and curb her, showing the slowness and necessity of the process of dislodging. Her grief is in several respects equivocal, mirroring the nature of the marriage (who told me it is worse to be lonely with two than alone?).

In my darkest moments I understand only too well what misfortune can leave a person in such a place. Bitterness is a very soft and comfortable armchair from which it is difficult indeed to extract oneself once one has decided to settle in it.

The portrait of Lilly and her current life and past which drop by drop forms in the mind of the reader is finely constructed, the silences, understatement and twofold interruptions in the stream of the diary are eloquent as well as potent.

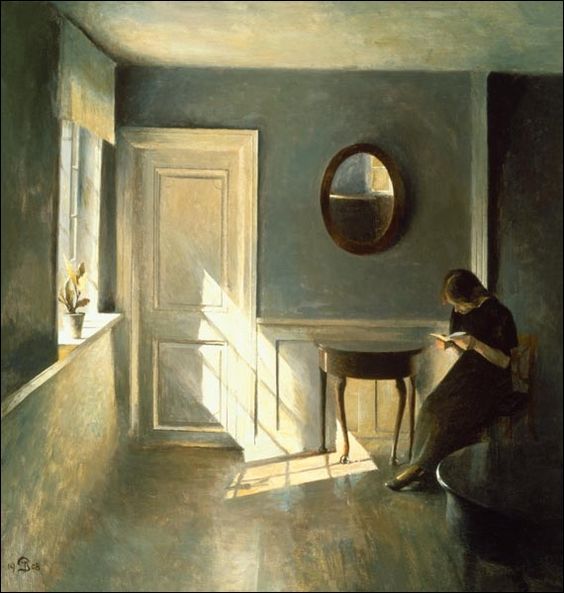

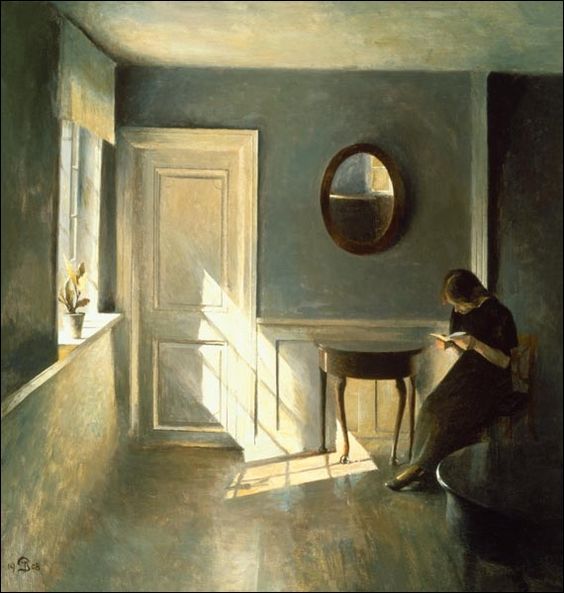

Reading Jessen’s articulate and luminous sentences drew me into the wintry silence of Lilly’s evenings, sitting alone at home, evoking the inwardness of the story magnificently. I smiled at the thought of myself as a woman reading about another woman alone in a silent house at night who also reads in silence, under a lamp – like looking at a painting depicting a person looking at a painting on which someone is looking at a painting.

No love is ever without grief.

Apart from the masterly evocation of the restrained emotions and inner experiences of growth and regained freedom of a woman who gets widowed, the novel through the description of everyday life and Lilly Høy’s personal history throws a light on the geography and history of the rural, poor area and life in a small village community in Denmark early 20th century (the diary spans the period 1904-1932) and the social changes taking place during that time (as aptly illustrated by Laura’s review), developments in which both spouses will play their part. And so the title of the novel ‘A change of time’ (literally from the Danish ‘A new time’) has a dual significance: both for Lilly Høy and for the village community dawns a new life, characterised by change and modernity.

Beautifully slow-paced, poetic and atmospheric, as an intimate meditation on how life goes on after the death of a spouse, A change of time reminded me of [b:Often I Am Happy|40766163|Often I Am Happy|Jens Christian Grøndahl|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1531133409l/40766163._SY75_.jpg|52112490] by Ida Jessen’s compatriot Jens Christian Grøndahl. As much as I loved Grøndahl’s novel, Ida Jessen’s novel touched me even more profoundly by its quiet finesse, elegant prose and subtle depiction of its social context and while reading, I marked numerous sentences that struck me for their insightfulness, honesty and truth. Though quite different, both novels hold a gratifying and heartening ending: Grøndahl’s empowering, Jessen’s of an embracing warmth and tenderness that made me vicariously glow in the dark.

A warmth unfolded and spread – I know now that it was tenderness.

My heart runs ahead of me. And I run after my heart. I cannot be without it.

While typing this review , I discovered that Ida Jessen wrote a pendant to Lilly’s story, this time seen from the perspective of her husband, Vigand ([b:Doktor Bagges anagrammer|33805880|Doktor Bagges anagrammer|Ida Jessen|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1484412103l/33805880._SY75_.jpg|54710013]). I like that premise of creating a diptych embodying an in-depth exploration of his personality by offering him the chance to tell his side of the story and I would love to read that book too if it happens to get translated in English or Dutch. My honest thanks to Net Galley, Edelweiss, Archipelago and Ida Jessen for the review copy of this novel – this excursion to Danish contemporary literature turned out a truly rewarding one.

(Paintings, as the one on the cover of the novel, by Vilhelm Hammershøi)

Thyregod, Denmark at the beginning of the 20th Century. Through diary entries, Ida Jessen conveys the life of a schoolteacher, Lilly Høy, starting with recounts of her visits to her husband Vigand Bagge who is in the hospital in another town, over her response to his death and her attempts to build herself a new life, find herself a new place and identity in the rural community she is living in and find attachment to her life again.

Slowly, as Lilly through subtle allusions, flashbacks, encounters and meaningful silences discloses her past, Lilly’s life turns out to have been far less conventional than one would have expected for a woman living at that time in such a remote rural place. Before she came to live in Thyregod where she met her husband, Lilly was a vivid and intelligent student, who moved to the rural village to put her ideals as a teacher into practise. Contemplating on the past and the present now she is alone, she reflects on her relationship with Vigand, her spouse for 22 years, who was a district physician ‘for fourteen impoverished and far-flung parishes’ – a stern, taciturn, stoic man, thirty years her elder and emotionally aloof – painting a portrait of their marriage in which tiny anecdotes and moments illustrate their inability to connect, revealing Lilly’s struggle with finding a way to live together with her husband, from her angling for a tender word or a caress to her walking on eggshells not to speak a word that would lead to more marital scorn.

Can one ask a person to show that they love you? Reason, that most faithful onlooker to the tribulations of others, says no.

But what says unreason?

There is the mourning for the person her husband was, but also the grieving for the lost life, the grieving for the lost self, a confrontation with the sacrifices made, the self-repression. The voice and thoughts of the one she has lived together with for such a long time continue to resonate in her own thoughts and acts, tending to censure and curb her, showing the slowness and necessity of the process of dislodging. Her grief is in several respects equivocal, mirroring the nature of the marriage (who told me it is worse to be lonely with two than alone?).

In my darkest moments I understand only too well what misfortune can leave a person in such a place. Bitterness is a very soft and comfortable armchair from which it is difficult indeed to extract oneself once one has decided to settle in it.

The portrait of Lilly and her current life and past which drop by drop forms in the mind of the reader is finely constructed, the silences, understatement and twofold interruptions in the stream of the diary are eloquent as well as potent.

Reading Jessen’s articulate and luminous sentences drew me into the wintry silence of Lilly’s evenings, sitting alone at home, evoking the inwardness of the story magnificently. I smiled at the thought of myself as a woman reading about another woman alone in a silent house at night who also reads in silence, under a lamp – like looking at a painting depicting a person looking at a painting on which someone is looking at a painting.

No love is ever without grief.

Apart from the masterly evocation of the restrained emotions and inner experiences of growth and regained freedom of a woman who gets widowed, the novel through the description of everyday life and Lilly Høy’s personal history throws a light on the geography and history of the rural, poor area and life in a small village community in Denmark early 20th century (the diary spans the period 1904-1932) and the social changes taking place during that time (as aptly illustrated by Laura’s review), developments in which both spouses will play their part. And so the title of the novel ‘A change of time’ (literally from the Danish ‘A new time’) has a dual significance: both for Lilly Høy and for the village community dawns a new life, characterised by change and modernity.

Beautifully slow-paced, poetic and atmospheric, as an intimate meditation on how life goes on after the death of a spouse, A change of time reminded me of [b:Often I Am Happy|40766163|Often I Am Happy|Jens Christian Grøndahl|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1531133409l/40766163._SY75_.jpg|52112490] by Ida Jessen’s compatriot Jens Christian Grøndahl. As much as I loved Grøndahl’s novel, Ida Jessen’s novel touched me even more profoundly by its quiet finesse, elegant prose and subtle depiction of its social context and while reading, I marked numerous sentences that struck me for their insightfulness, honesty and truth. Though quite different, both novels hold a gratifying and heartening ending: Grøndahl’s empowering, Jessen’s of an embracing warmth and tenderness that made me vicariously glow in the dark.

A warmth unfolded and spread – I know now that it was tenderness.

My heart runs ahead of me. And I run after my heart. I cannot be without it.

While typing this review , I discovered that Ida Jessen wrote a pendant to Lilly’s story, this time seen from the perspective of her husband, Vigand ([b:Doktor Bagges anagrammer|33805880|Doktor Bagges anagrammer|Ida Jessen|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1484412103l/33805880._SY75_.jpg|54710013]). I like that premise of creating a diptych embodying an in-depth exploration of his personality by offering him the chance to tell his side of the story and I would love to read that book too if it happens to get translated in English or Dutch. My honest thanks to Net Galley, Edelweiss, Archipelago and Ida Jessen for the review copy of this novel – this excursion to Danish contemporary literature turned out a truly rewarding one.

(Paintings, as the one on the cover of the novel, by Vilhelm Hammershøi)