Take a photo of a barcode or cover

buddhafish 's review for:

The Divine Comedy: Volume 1: Hell

by Dante Alighieri

49th book of 2021. Artist for this review is the magnificent French artist Gustave Doré, who did illustrations for The Divine Comedy. There will be many in this review, because they are hauntingly beautiful.

In Brighton a long time ago now I picked up Clive James’ complete The Divine Comedy translation and have poked a few times, non-committedly into it. I’ll read it properly once I’ve finished reading the rest of Sayers (and maybe after Ciardi too). I’ve been wanting to read Dante for a long time now (isn’t it funny how people say Dante, rather than Alighieri, when all other writers are known by their surnames?) and so I began my research. I also began reading.

Sayers keeps the original Italian terza rima rhyme scheme which many translation omit, including James. I wondered if this meant that the translation would be “less honest”, but frankly, it was the decision between closer to Dante’s precise words or closer to Dante’s precise rhyme/rhythm. In the end there were three reasons I stuck with Sayers, (1) Umberto Eco says in an essay that Sayers “does the best in at least partially preserving the hendecasyllables and the rhyme” and (2) after every canto (all 33), Sayers includes fairly extensive notes that outline context, allusions, meaning, etc and (3) I began reading it whilst still researching and realised I was in love, to quote Catch-22—It was love at first sight.

Before anything else the very concept of Hell/Inferno sets my imagination alight: the poet Virgil guides Dante Alighieri himself into the depths of Hell. And what further set it alight was the detail in which Dante has constructed Hell, with bridges and slopes (and Sayers does her best, with diagrams, to track exactly how the two poets moved about), and how fantastical it all is. There are giants, centaurs, figures from myth like Odysseus himself, other writers such as Homer, countless figures from Dante’s real-life (particularly political “enemies”), raining fire, rivers of lava, beasts, people as trees or people with their heads on backwards of any number of other Ovidian metamorphoses. In a way, I think having a general knowledge of Greek/Roman myth would be beneficial for the reading of Dante but not necessarily essential. If you are reading Sayers, she breaks down a lot of the allusions and references, as I said, but knowing them yourself would of course allow for greater and deeper meaning.

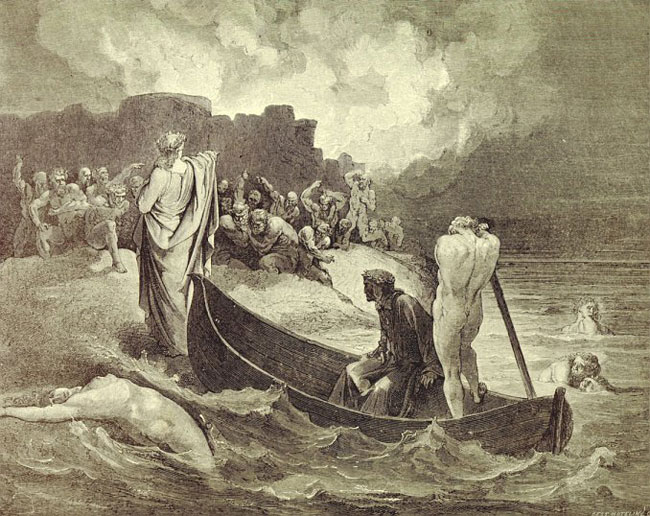

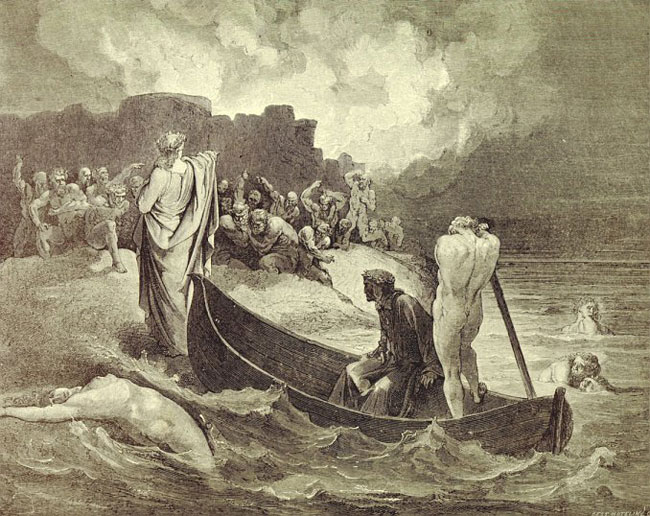

I was completely bowled over by how entertaining this was, how humorous at times, how violent and intelligent and how purely addictive. I’ll admit that like my reading of Joyce, I paced about my bedroom in an imagined auditorium reading the cantos aloud. After each canto I read Sayers’ fantastic notes and pored through online resources to learn more. Writing this review is difficult because I have so much I want to say, I can almost say nothing. It’s impossible to know where to start. So I will hang my rambling from the amazing artwork by Doré; it captures the feeling and atmosphere and pure dramatics of the poem far better than I can. The only thing the artwork doesn't manage to capture is the humour, for there is humour, though it may be hard to believe. Dante writes himself realistically, by which I mean, he hides behind Virgil, he cries a lot (at the beginning of Purgatory he must wash his face of the tears he shed in Hell), and generally finds him startled by everything they come across in Hell, the poor poet even faints on several occasions. There’s no Kafkaesque acceptance of what he sees: Dante is horrified by the horrors of Hell. For example, here is Dante clinging to the arm of Virgil as he pushes Filippo Argenti back into the river Styx in the Fifth Circle.

Or Dante as he remains on the boat as Virgil steps out to confront the devils outside the city of Dis:

(Oddly, one of the most fascinating parts of the whole Inferno for me was the detail. I've mentioned it briefly in regard to the circles themselves and how the poets move between them via paths and bridges, but more so, regarding Dante himself. There are countless allusions throughout to the fact that Dante is in fact "alive", as the devils call out here, 'why walks this man, / Undead, the kingdom of the dead?' At one point, fairly early on, it describes how rocks and pebbles are shifted and kicked by Dante's movements around Hell, but not Virgil's. He casts no shadow. And for the extreme detail, Dante mentions that when he speaks, his throat moves, where of course Virgil's doesn't, or anyone else's either.)

The humour is only slight throughout the horrors of Hell. In Canto V we see the lustful who are caught in a permanent gale/hurricane of wind.

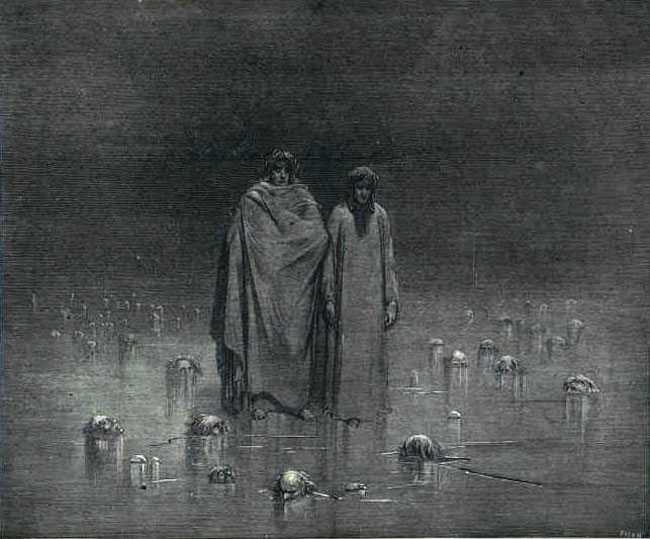

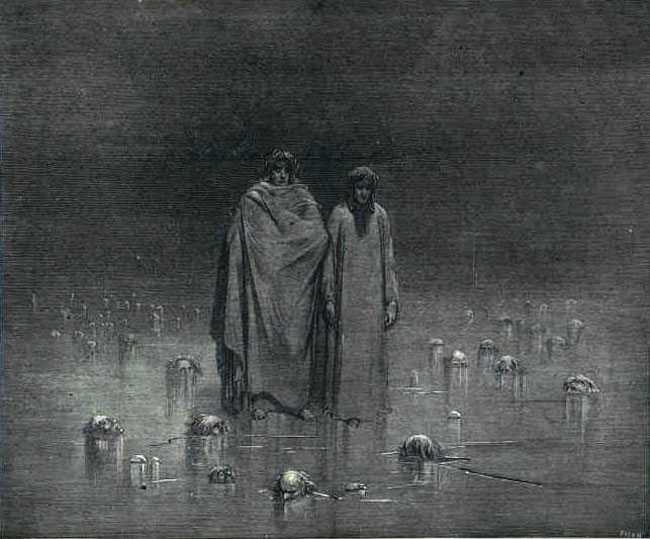

Or one of the most harrowing images, the poets walk Cocytus in the ninth (and lowest) circle of Hell. It is described as a frozen lake rather than a river, and traitors are submerged in the ice to varying degrees, dependent on their crimes in life.

Of course the poets find their way out of Hell, after passing Satan himself (climbing on Satan, even). Dante now must wash the tears from his face. I've actually become rather obsessed and have been sitting around wondering if it's possible to go to Dante School, or become a dedicated Dante scholar. Or to somehow spend the rest of my life reading Inferno. First though, I must read the other two, before I get carried away. From here the plan is to read the rest of Sayers' beautiful translation (though the final one was finished by Barbara Reynolds in 1962 following Sayers' death) and then read the Ciardi translation. After that perhaps Clive James, though from what I've read so far, it seems like one to leave for later. Perhaps Hollander before James. I may add more to this review as I inevitably learn more. I will write new reviews for future translations read to compare them with one another and slowly, hopefully, grow a rather complete understanding of this seminal and magnificent work; it is a certain favourite.

But first, Mount Purgatory.

In Brighton a long time ago now I picked up Clive James’ complete The Divine Comedy translation and have poked a few times, non-committedly into it. I’ll read it properly once I’ve finished reading the rest of Sayers (and maybe after Ciardi too). I’ve been wanting to read Dante for a long time now (isn’t it funny how people say Dante, rather than Alighieri, when all other writers are known by their surnames?) and so I began my research. I also began reading.

Sayers keeps the original Italian terza rima rhyme scheme which many translation omit, including James. I wondered if this meant that the translation would be “less honest”, but frankly, it was the decision between closer to Dante’s precise words or closer to Dante’s precise rhyme/rhythm. In the end there were three reasons I stuck with Sayers, (1) Umberto Eco says in an essay that Sayers “does the best in at least partially preserving the hendecasyllables and the rhyme” and (2) after every canto (all 33), Sayers includes fairly extensive notes that outline context, allusions, meaning, etc and (3) I began reading it whilst still researching and realised I was in love, to quote Catch-22—It was love at first sight.

Midway this way of life we're bound upon,

I woke to find myself in a dark wood,

Where the right road was wholly lost and gone.

Ay me! how hard to speak of it—that rude

And rough and stubborn forest! the mere breath

Of memory stirs the old fear in the blood;

It is so bitter, it goes nigh to death;

Yet there I gained such good, that, to convey

The tale, I'll write what else I found therewith.

Before anything else the very concept of Hell/Inferno sets my imagination alight: the poet Virgil guides Dante Alighieri himself into the depths of Hell. And what further set it alight was the detail in which Dante has constructed Hell, with bridges and slopes (and Sayers does her best, with diagrams, to track exactly how the two poets moved about), and how fantastical it all is. There are giants, centaurs, figures from myth like Odysseus himself, other writers such as Homer, countless figures from Dante’s real-life (particularly political “enemies”), raining fire, rivers of lava, beasts, people as trees or people with their heads on backwards of any number of other Ovidian metamorphoses. In a way, I think having a general knowledge of Greek/Roman myth would be beneficial for the reading of Dante but not necessarily essential. If you are reading Sayers, she breaks down a lot of the allusions and references, as I said, but knowing them yourself would of course allow for greater and deeper meaning.

I was completely bowled over by how entertaining this was, how humorous at times, how violent and intelligent and how purely addictive. I’ll admit that like my reading of Joyce, I paced about my bedroom in an imagined auditorium reading the cantos aloud. After each canto I read Sayers’ fantastic notes and pored through online resources to learn more. Writing this review is difficult because I have so much I want to say, I can almost say nothing. It’s impossible to know where to start. So I will hang my rambling from the amazing artwork by Doré; it captures the feeling and atmosphere and pure dramatics of the poem far better than I can. The only thing the artwork doesn't manage to capture is the humour, for there is humour, though it may be hard to believe. Dante writes himself realistically, by which I mean, he hides behind Virgil, he cries a lot (at the beginning of Purgatory he must wash his face of the tears he shed in Hell), and generally finds him startled by everything they come across in Hell, the poor poet even faints on several occasions. There’s no Kafkaesque acceptance of what he sees: Dante is horrified by the horrors of Hell. For example, here is Dante clinging to the arm of Virgil as he pushes Filippo Argenti back into the river Styx in the Fifth Circle.

Or Dante as he remains on the boat as Virgil steps out to confront the devils outside the city of Dis:

A long way round we had to navigate

Before we came to where the ferryman

Roared: 'Out with you now, for here's the gate!'

Thousand and more, thronging the barbican,

I saw, of spirits fallen from Heaven, who cried

Angrily: 'Who goes there? why walks this man,

Undead, the kingdom of the dead?' My guide,

Wary and wise, made signs to them, to show

He sought a secret parley. Then their pride

Abating somewhat, they called out: 'Why, so!

Come thou within, and bid that fellow begone—

That rash intruder on our realm below.

(Oddly, one of the most fascinating parts of the whole Inferno for me was the detail. I've mentioned it briefly in regard to the circles themselves and how the poets move between them via paths and bridges, but more so, regarding Dante himself. There are countless allusions throughout to the fact that Dante is in fact "alive", as the devils call out here, 'why walks this man, / Undead, the kingdom of the dead?' At one point, fairly early on, it describes how rocks and pebbles are shifted and kicked by Dante's movements around Hell, but not Virgil's. He casts no shadow. And for the extreme detail, Dante mentions that when he speaks, his throat moves, where of course Virgil's doesn't, or anyone else's either.)

The humour is only slight throughout the horrors of Hell. In Canto V we see the lustful who are caught in a permanent gale/hurricane of wind.

A place made dumb of every glimmer of light,

Which bellows like tempestuous ocean birling

In the batter of a two-way wind's buffet and fight.

The blast of hell that never rests from whirling

Harries the spirits along in the sweep of its swath,

And vexes them, for ever beating and hurling.

When they are borne to the rim of the ruinous path

With cry and wail and shriek they are caught by the gust,

Railing and cursing the power of the Lord's wrath.

Into this torment carnal sinners are thrust,

So I was told—the sinners who make their reason

Bond thrall under the yoke of their lust.

Or one of the most harrowing images, the poets walk Cocytus in the ninth (and lowest) circle of Hell. It is described as a frozen lake rather than a river, and traitors are submerged in the ice to varying degrees, dependent on their crimes in life.

I thought I saw a shady mass appear;

Then shrank behind my leader from the blast,

Because there was no other cabin here.

I stood (with fear I write it) where at least

The shades, quite covered by the frozen sheet,

Gleamed through the ice like straws in crystal glassed;

Some lie at length and others stand in it,

This one upon his head, and that upright,

Another like a bow bent to feet.

Of course the poets find their way out of Hell, after passing Satan himself (climbing on Satan, even). Dante now must wash the tears from his face. I've actually become rather obsessed and have been sitting around wondering if it's possible to go to Dante School, or become a dedicated Dante scholar. Or to somehow spend the rest of my life reading Inferno. First though, I must read the other two, before I get carried away. From here the plan is to read the rest of Sayers' beautiful translation (though the final one was finished by Barbara Reynolds in 1962 following Sayers' death) and then read the Ciardi translation. After that perhaps Clive James, though from what I've read so far, it seems like one to leave for later. Perhaps Hollander before James. I may add more to this review as I inevitably learn more. I will write new reviews for future translations read to compare them with one another and slowly, hopefully, grow a rather complete understanding of this seminal and magnificent work; it is a certain favourite.

But first, Mount Purgatory.