You need to sign in or sign up before continuing.

Take a photo of a barcode or cover

seanquistador 's review for:

The Prose Edda

by Snorri Sturluson

The historical figures and mythological structure of the cosmos found in the Prose Edda existed in an oral tradition and skaldic poems long before an Icelandic nobleman named Snorri purportedly decided to put them down on paper. Much of the poetry concerning the Norse gods is sadly lost as a consequence of that tradition.

Snorri's work is an obvious attempt to preserve some of what was lost and promote the continuation of a poetic tradition that had begun to fade by the 13th century in the face of Christianity, the last bastions of a heathen pantheon of northern Europe making a last stand in Scandanavia. Faced with the spread of Christianity and its Bible, Snorri observed his people had no solid theological work upon which to fall back on as a resource, and thus composed what is known as the Prose Edda.

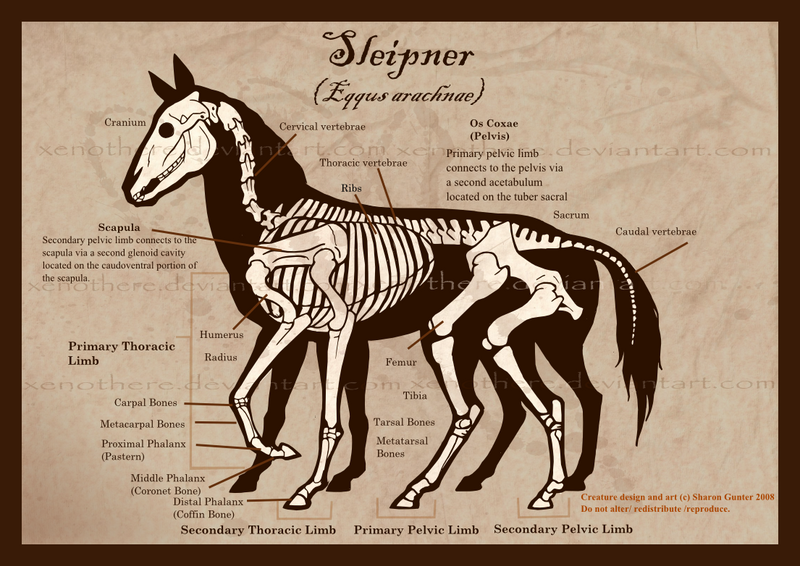

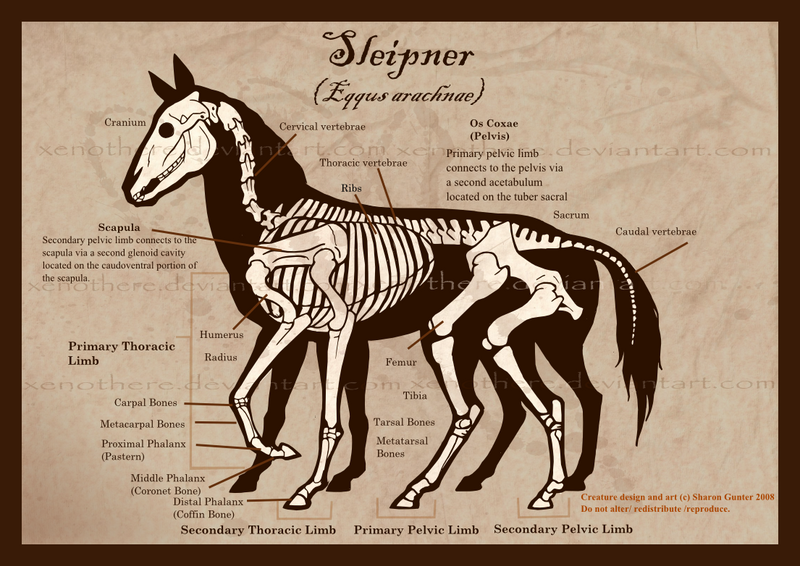

God + Giant = Horse + Spider (Sleipnir). Only in mythology.

The Prose Edda is generally composed of a Prologue and three parts:

Gylfaginning

The largest portion is given to the Gylfaginning, and serves as the meat of the Nordic cosmic history. It involves the travel of a Scandanavian king, Gylfi, disguised as Gangleri, to visit Odin, who likewise disguises himself as three kings (it seems to be a theme amongst gods to disguise themselves simply because they can), and inquire about the nature of Odin, who has migrated from his original lands (Troy--yes, that Troy). In the process of their discussion, Gylfi learns about the creation and inevitable destruction of the world, as well as the various gods of the Nordic pantheon.

Gylfi speaking to Odin, disguised as three kings

The compilation was meant as a guide, maybe even a bible of sorts, to which people and poets could refer--a handy thing in any age, really. The work refers heavily to the Poetic Edda, which itself is more a collection than a consciously assembled work, compiling bits of mythological history and assembling them into a relatively linear whole.

The dialogue begins with the three kings stating Gylfi must become wiser (i.e., more knowledgeable about mythology) or he will not be permitted to leave alive. It's a pretty thin veneer for a contrived conversation meant to unsubtly wheedle information about the foundation of the world, and while probably the most informative in a general sense, comes off a bit forced. Here we have a disguised kind seeking mythological knowledge, asking surprisingly pointed questions about topics which he knows nothing about, and can therefore hardly know when he's received all the information about something.

The history of the Norse Gods is one of strange contradictions and bizarre world creation legends tending toward the Munchhausen Trilemma--not that science has found the bedrock for an explanation of a beginning yet, either, but it seems pointed in a comparatively sensible direction.

The contradictions stem from an effort on, presumably, Sturleson's part to link Norse gods to a physical location and line of people, the AEsir, on Earth, which we'll get to later.

The gods, Odin and his famous offspring and brethren, were a race of people who were born of a giant who was born of the very first giant (a term usually, but not always, restricted to Very Large People).

What did not simply appear from the void, such as light and waterfalls and cows, came from a single giant, Ymir (who was a giant, even though not all giants are giant) that, having been slain by his grandchildren, Odin included, had all his body parts turned into the various landscapes fo the world. When Gylfi/Gangleri asks where one thing or another comes from (e.g., What did the giant eat if there was only light and dark and such? Answer: A cow formed spontaneously from icicle drippings. How fortunate.), one gets the impression that pretty much anything can preclude the formation of something else based purely upon necessity, and in that fashion "it's turtles all the way down."

This seems a rather linear and sensible description of the ascent of Odin, et al, to the seat of power, not unlike the ascension of Zeus and other Greek gods after they slay their elemental father. Where it gets confusing is when we consider the Prologue to the Gylfiginning.

In the prologue, despite having been the grandsons of what was the first humanoid being, Ymir the giant, the "gods" hail from Troy, exist post-Talmudic flood, and are called AEsir. They are the current line in many generations and have migrated all the way from western Anatolia to settle in Sweden.

We also learn in the Gylfaginning that Odin and his brethren were actually just people who became godlike because of their great powers and are immortal so long as they eat magical apples overseen by another "god". While other gods are innately godlike, the Norse Gods are more like superheroes. We have an All Father in Odin, yet he and all the other gods have anticipated their doom in the final battle (Ragnarok), in which everyone dies, even the warriors who died well and are granted the opportunity to participate in this final battle. Rather grim, though there are hints of an afterlife afterwards, even if the fate of everyone involved in Ragnarok isn't clear--clarification is welcome.

How these two pathways rectify with one another is beyond my understanding. Only in the realm of mythmaking and religion can a story be told several starkly different ways and each of them be true. The best explanation I can come up with is that by tying these gods to a place in time and making them wise humans rather than gods born of a giant Snorri may have been attempting to avoid being outed as heretical, as Christopher Tolkien's foreword to J.R.R Tolkien's The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrun describe Christian missionaries as rather zealous and intent on squelching paganism.

This is a resource for myth-writing poets, so it can hardly be expected to be believable, or without contradiction and hyperbole. It probably suffers from an effort to integrate some features of Christianity that were invariably absent from the oral tradition and an inexplicable compulsion to tie Asgard, the home of the gods, to Troy and its King Priam.

Skaldskaparmal

The Skaldskaparmal is a dialogue between AEgir and Bragi, the god of poetry, and provides examples of the proper idioms used to refer to people, places, and things (e.g., Gold is known as Sif's hair, pretty much everyone's bane, and a number of other, more obscure references based on Nordic myths) when composing poetry.

For example, Suttung's Mead gives the gift of poetry to any who drink it. Odin stole the mead by drinking all of it, then vomited two thirds out while flying over Asgard in bird form (to escape the giant he was fleeing), with the final third blowing out his rear. This final third is known as the "bad poet's portion". The implication here ought to be clear.

This also confirms the grand thesis of scatalogical theorist,Taro Gomi.

In this section it is plain to see mechanisms utilized by Tolkien in his writing. Projected downfalls of one God or monster in the Edda are often referred to as The Bane of [insert character], which naturally brings your mind to bear on particulars from the Lord of the Rings, such as Isildur's Bane.

Hattatal

This book loses a star because it inexplicably lacks the Hattatal, which many other versions contain. The Hattatal was composed by Sturleson in an effort to demonstrate appropriate meter and method used when composing poetry.

In all, this work is a fantastic and convoluted resource for figures, names, locations, and their functions in Norse mythology. If you want to know why certain gods do the things they do (e.g., fight frost giants, appear in cinematic features, etc.), the name and features of the gigantic hall in which each lives, the particular traits that are their weaknesses and strengths, where monsters like Jormungand originate (usually Loki), it's all here.

The Midgard Serpent, Jormungand. Not a dog dropping.

In all, an informative if not gripping read. However, if you're looking for a reference book, you're probably better off finding a Dictionary of Norse Gods, or something of that ilk.

Snorri's work is an obvious attempt to preserve some of what was lost and promote the continuation of a poetic tradition that had begun to fade by the 13th century in the face of Christianity, the last bastions of a heathen pantheon of northern Europe making a last stand in Scandanavia. Faced with the spread of Christianity and its Bible, Snorri observed his people had no solid theological work upon which to fall back on as a resource, and thus composed what is known as the Prose Edda.

God + Giant = Horse + Spider (Sleipnir). Only in mythology.

The Prose Edda is generally composed of a Prologue and three parts:

Gylfaginning

Skaldskaparmal

Hattatal

Gylfaginning

The largest portion is given to the Gylfaginning, and serves as the meat of the Nordic cosmic history. It involves the travel of a Scandanavian king, Gylfi, disguised as Gangleri, to visit Odin, who likewise disguises himself as three kings (it seems to be a theme amongst gods to disguise themselves simply because they can), and inquire about the nature of Odin, who has migrated from his original lands (Troy--yes, that Troy). In the process of their discussion, Gylfi learns about the creation and inevitable destruction of the world, as well as the various gods of the Nordic pantheon.

Gylfi speaking to Odin, disguised as three kings

The compilation was meant as a guide, maybe even a bible of sorts, to which people and poets could refer--a handy thing in any age, really. The work refers heavily to the Poetic Edda, which itself is more a collection than a consciously assembled work, compiling bits of mythological history and assembling them into a relatively linear whole.

The dialogue begins with the three kings stating Gylfi must become wiser (i.e., more knowledgeable about mythology) or he will not be permitted to leave alive. It's a pretty thin veneer for a contrived conversation meant to unsubtly wheedle information about the foundation of the world, and while probably the most informative in a general sense, comes off a bit forced. Here we have a disguised kind seeking mythological knowledge, asking surprisingly pointed questions about topics which he knows nothing about, and can therefore hardly know when he's received all the information about something.

"What more of importance can be said of the ash [Ygdrasil, the world tree]?"

The history of the Norse Gods is one of strange contradictions and bizarre world creation legends tending toward the Munchhausen Trilemma--not that science has found the bedrock for an explanation of a beginning yet, either, but it seems pointed in a comparatively sensible direction.

The contradictions stem from an effort on, presumably, Sturleson's part to link Norse gods to a physical location and line of people, the AEsir, on Earth, which we'll get to later.

The gods, Odin and his famous offspring and brethren, were a race of people who were born of a giant who was born of the very first giant (a term usually, but not always, restricted to Very Large People).

What did not simply appear from the void, such as light and waterfalls and cows, came from a single giant, Ymir (who was a giant, even though not all giants are giant) that, having been slain by his grandchildren, Odin included, had all his body parts turned into the various landscapes fo the world. When Gylfi/Gangleri asks where one thing or another comes from (e.g., What did the giant eat if there was only light and dark and such? Answer: A cow formed spontaneously from icicle drippings. How fortunate.), one gets the impression that pretty much anything can preclude the formation of something else based purely upon necessity, and in that fashion "it's turtles all the way down."

This seems a rather linear and sensible description of the ascent of Odin, et al, to the seat of power, not unlike the ascension of Zeus and other Greek gods after they slay their elemental father. Where it gets confusing is when we consider the Prologue to the Gylfiginning.

In the prologue, despite having been the grandsons of what was the first humanoid being, Ymir the giant, the "gods" hail from Troy, exist post-Talmudic flood, and are called AEsir. They are the current line in many generations and have migrated all the way from western Anatolia to settle in Sweden.

We also learn in the Gylfaginning that Odin and his brethren were actually just people who became godlike because of their great powers and are immortal so long as they eat magical apples overseen by another "god". While other gods are innately godlike, the Norse Gods are more like superheroes. We have an All Father in Odin, yet he and all the other gods have anticipated their doom in the final battle (Ragnarok), in which everyone dies, even the warriors who died well and are granted the opportunity to participate in this final battle. Rather grim, though there are hints of an afterlife afterwards, even if the fate of everyone involved in Ragnarok isn't clear--clarification is welcome.

How these two pathways rectify with one another is beyond my understanding. Only in the realm of mythmaking and religion can a story be told several starkly different ways and each of them be true. The best explanation I can come up with is that by tying these gods to a place in time and making them wise humans rather than gods born of a giant Snorri may have been attempting to avoid being outed as heretical, as Christopher Tolkien's foreword to J.R.R Tolkien's The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrun describe Christian missionaries as rather zealous and intent on squelching paganism.

This is a resource for myth-writing poets, so it can hardly be expected to be believable, or without contradiction and hyperbole. It probably suffers from an effort to integrate some features of Christianity that were invariably absent from the oral tradition and an inexplicable compulsion to tie Asgard, the home of the gods, to Troy and its King Priam.

Skaldskaparmal

The Skaldskaparmal is a dialogue between AEgir and Bragi, the god of poetry, and provides examples of the proper idioms used to refer to people, places, and things (e.g., Gold is known as Sif's hair, pretty much everyone's bane, and a number of other, more obscure references based on Nordic myths) when composing poetry.

For example, Suttung's Mead gives the gift of poetry to any who drink it. Odin stole the mead by drinking all of it, then vomited two thirds out while flying over Asgard in bird form (to escape the giant he was fleeing), with the final third blowing out his rear. This final third is known as the "bad poet's portion". The implication here ought to be clear.

This also confirms the grand thesis of scatalogical theorist,Taro Gomi.

In this section it is plain to see mechanisms utilized by Tolkien in his writing. Projected downfalls of one God or monster in the Edda are often referred to as The Bane of [insert character], which naturally brings your mind to bear on particulars from the Lord of the Rings, such as Isildur's Bane.

Hattatal

This book loses a star because it inexplicably lacks the Hattatal, which many other versions contain. The Hattatal was composed by Sturleson in an effort to demonstrate appropriate meter and method used when composing poetry.

In all, this work is a fantastic and convoluted resource for figures, names, locations, and their functions in Norse mythology. If you want to know why certain gods do the things they do (e.g., fight frost giants, appear in cinematic features, etc.), the name and features of the gigantic hall in which each lives, the particular traits that are their weaknesses and strengths, where monsters like Jormungand originate (usually Loki), it's all here.

The Midgard Serpent, Jormungand. Not a dog dropping.

In all, an informative if not gripping read. However, if you're looking for a reference book, you're probably better off finding a Dictionary of Norse Gods, or something of that ilk.