Take a photo of a barcode or cover

A review by fionnualalirsdottir

New Grub Street by George Gissing

Did you ever hear of the phenomenon of 'the three-volume novel'?

It wasn't a trilogy as we know the concept today but a single novel published in three parts. It became very popular in 19th century England around the time that 'subscription libraries' were common, and there's a link between the two. You see, the owners of subscription libraries charged the users a yearly rate. There was a cheap rate, which allowed subscribers to borrow one book at a time, and a more expensive rate which allowed them to borrow up to three books at a time. If all the popular novels of the day were in three volumes, and you were paying the cheap rate, you can imagine the frustration of having to wait to read the next chapter of the novel you'd become engrossed in until it was available. You'd soon change your subscription! So the three-volume novel suited the subscription library owners very well. It also suited the publishers because they made enough money out of selling the first volume to the subscription libraries to help with the costs of printing the second, etc.

How did it suit the writers of three-volume novels though? Not so well, if we are to go by George Gissing's story of one such writer in London in the 1880s. When a publisher agreed to buy the first volume of a novel main character Edwin Reardon was working on, they gave him a low price because he hadn't yet finished the final volume. But that wasn't the worst aspect for the poor writer. In order to make his novel fill three volumes—a total of maybe eight or nine hundred pages—he had to stretch out what might have made a good quality single-volume novel by adding all sorts of filling, including melodrama and stock-phrasing. If he couldn't or wouldn't do that, he was doomed. Edwin couldn't do it. Would you blame him?

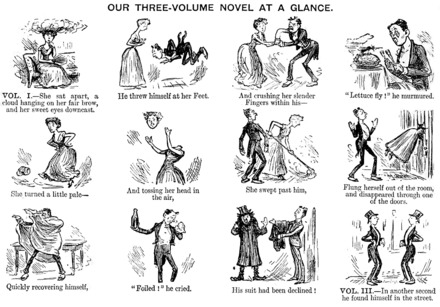

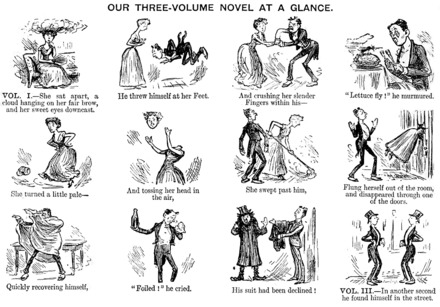

I was curious about the phenomenon of the three-volume novel so I did a bit of wiki research and that's how I found that cartoon from Punch.

I found some great quotes about the three-volume novel too, including this one from Oscar Wilde: 'Anybody can write a three-volume novel, it merely requires a complete ignorance of both life and literature!'

And here's another Wilde quip from 'The Importance of Being Earnest': [The attaché-case] contained the manuscript of a three-volume novel of more than usually revolting sentimentality'.

In [b:Three Men in a Boat|4921|Three Men in a Boat (Three Men, #1)|Jerome K. Jerome|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1630492021l/4921._SY75_.jpg|4476508], written in the 1880s around the same time as Gissing's book, Jerome K Jerome's narrator says: 'the heroine of the three-volume novel always dines [at Maidenhead] when she goes out on the spree with somebody else's husband'.

The three-volume novel is even mentioned in Jane Austin's [b:Pride and Prejudice|1885|Pride and Prejudice|Jane Austen|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1320399351l/1885._SY75_.jpg|3060926] back in 1813 (itself a three-volume novel originally): Darcy took up a book; Miss Bingley did the same...At length, quite exhausted by the attempt to be amused with her own book, which she had only chosen because it was the second volume of his, she gave a great yawn and said, "How pleasant it is to spend an evening in this way! I declare after all there is no enjoyment like reading! How much sooner one tires of anything than of a book! When I have a house of my own, I shall be miserable if I have not an excellent library."

………….....................................................

Ok, enough with the filling, I hear you say.

George Gissing's New Grub Street isn't just about the struggles of Edwin Reardon to write a three-volume novel. Grub Street itself was an eighteenth century London street where poor writers, and small publishers and booksellers, plied their trades. It was renamed Milton Street in the nineteenth century, but Gissing, by recalling it in his title, is setting out his stall, as it were. Inside the covers of his own very long book (which was originally published as a three-volume novel), there are many subplots and many characters. Some of those characters are novelists like Edwin Reardon, incapable of writing what the publishers demand; some are writers for periodicals; and some are journalists for newspapers. They are mostly poor and mostly struggling but none of them write in the Punch cartoon style illustrated above, it has to be said.

Because while Gissing's story is a little long-winded in places, especially in the first third, I wouldn't dream of accusing him of filling it out with melodrama or stock-phrasing—indeed some of his descriptions of poor writers and journalists are exceedingly good. Take Mr Quarmby who wore a coat between brown and blue, hanging in capacious shapelessness, a waistcoat half-open for lack of buttons and with one of the pockets coming unsewn, a pair of bronze-hued trousers which had all run to knee... You can see him clearly, can't you? And maybe you can hear him too, because, when he was excited, Mr Quarmby talked in thick, rather pompous tones, with a pant at the end of a sentence.

Yes, the writing is colourful and the plots and characters Gissing develops reveal a great understanding of both life and literature.

…………..................................................

Why did I choose to read this very long nineteenth-century novel, you might wonder?

Well, this is a perfect case of 'one book leading to another'. I'd read a lot of books by Gerald Murnane a couple of months ago and he mentioned George Gissing more than once when recalling his favourite writers. So I went looking for one of Gissing's book. The one I found was called [b:The Odd Women|675037|The Odd Women|George Gissing|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1177017769l/675037._SY75_.jpg|661046], but after finishing that very interesting novel, I wasn't completely satisfied that I understood why Murnane valued Gissing so much—although I had the beginnings of an idea. So I decided to read another one, and now that I've finished New Grub Street, I have a better understanding of the attraction of Gissing's books for Murnane. Murnane was a struggling writer himself for a long time and he refused to write in the conventional way publishers might have preferred. But that may be only part of the explanation for his love of Gissing. As I see it, Gissing writes very fine independent-minded women characters, and unusual women characters in literature are one of the things Murnane seems to value highly in his own reading: the 'odd' women who step outside the norm of their times; the 'odd' women who love reading and writing.

Yes, on reflection, I think that may well be it.

It wasn't a trilogy as we know the concept today but a single novel published in three parts. It became very popular in 19th century England around the time that 'subscription libraries' were common, and there's a link between the two. You see, the owners of subscription libraries charged the users a yearly rate. There was a cheap rate, which allowed subscribers to borrow one book at a time, and a more expensive rate which allowed them to borrow up to three books at a time. If all the popular novels of the day were in three volumes, and you were paying the cheap rate, you can imagine the frustration of having to wait to read the next chapter of the novel you'd become engrossed in until it was available. You'd soon change your subscription! So the three-volume novel suited the subscription library owners very well. It also suited the publishers because they made enough money out of selling the first volume to the subscription libraries to help with the costs of printing the second, etc.

How did it suit the writers of three-volume novels though? Not so well, if we are to go by George Gissing's story of one such writer in London in the 1880s. When a publisher agreed to buy the first volume of a novel main character Edwin Reardon was working on, they gave him a low price because he hadn't yet finished the final volume. But that wasn't the worst aspect for the poor writer. In order to make his novel fill three volumes—a total of maybe eight or nine hundred pages—he had to stretch out what might have made a good quality single-volume novel by adding all sorts of filling, including melodrama and stock-phrasing. If he couldn't or wouldn't do that, he was doomed. Edwin couldn't do it. Would you blame him?

I was curious about the phenomenon of the three-volume novel so I did a bit of wiki research and that's how I found that cartoon from Punch.

I found some great quotes about the three-volume novel too, including this one from Oscar Wilde: 'Anybody can write a three-volume novel, it merely requires a complete ignorance of both life and literature!'

And here's another Wilde quip from 'The Importance of Being Earnest': [The attaché-case] contained the manuscript of a three-volume novel of more than usually revolting sentimentality'.

In [b:Three Men in a Boat|4921|Three Men in a Boat (Three Men, #1)|Jerome K. Jerome|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1630492021l/4921._SY75_.jpg|4476508], written in the 1880s around the same time as Gissing's book, Jerome K Jerome's narrator says: 'the heroine of the three-volume novel always dines [at Maidenhead] when she goes out on the spree with somebody else's husband'.

The three-volume novel is even mentioned in Jane Austin's [b:Pride and Prejudice|1885|Pride and Prejudice|Jane Austen|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1320399351l/1885._SY75_.jpg|3060926] back in 1813 (itself a three-volume novel originally): Darcy took up a book; Miss Bingley did the same...At length, quite exhausted by the attempt to be amused with her own book, which she had only chosen because it was the second volume of his, she gave a great yawn and said, "How pleasant it is to spend an evening in this way! I declare after all there is no enjoyment like reading! How much sooner one tires of anything than of a book! When I have a house of my own, I shall be miserable if I have not an excellent library."

………….....................................................

Ok, enough with the filling, I hear you say.

George Gissing's New Grub Street isn't just about the struggles of Edwin Reardon to write a three-volume novel. Grub Street itself was an eighteenth century London street where poor writers, and small publishers and booksellers, plied their trades. It was renamed Milton Street in the nineteenth century, but Gissing, by recalling it in his title, is setting out his stall, as it were. Inside the covers of his own very long book (which was originally published as a three-volume novel), there are many subplots and many characters. Some of those characters are novelists like Edwin Reardon, incapable of writing what the publishers demand; some are writers for periodicals; and some are journalists for newspapers. They are mostly poor and mostly struggling but none of them write in the Punch cartoon style illustrated above, it has to be said.

Because while Gissing's story is a little long-winded in places, especially in the first third, I wouldn't dream of accusing him of filling it out with melodrama or stock-phrasing—indeed some of his descriptions of poor writers and journalists are exceedingly good. Take Mr Quarmby who wore a coat between brown and blue, hanging in capacious shapelessness, a waistcoat half-open for lack of buttons and with one of the pockets coming unsewn, a pair of bronze-hued trousers which had all run to knee... You can see him clearly, can't you? And maybe you can hear him too, because, when he was excited, Mr Quarmby talked in thick, rather pompous tones, with a pant at the end of a sentence.

Yes, the writing is colourful and the plots and characters Gissing develops reveal a great understanding of both life and literature.

…………..................................................

Why did I choose to read this very long nineteenth-century novel, you might wonder?

Well, this is a perfect case of 'one book leading to another'. I'd read a lot of books by Gerald Murnane a couple of months ago and he mentioned George Gissing more than once when recalling his favourite writers. So I went looking for one of Gissing's book. The one I found was called [b:The Odd Women|675037|The Odd Women|George Gissing|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1177017769l/675037._SY75_.jpg|661046], but after finishing that very interesting novel, I wasn't completely satisfied that I understood why Murnane valued Gissing so much—although I had the beginnings of an idea. So I decided to read another one, and now that I've finished New Grub Street, I have a better understanding of the attraction of Gissing's books for Murnane. Murnane was a struggling writer himself for a long time and he refused to write in the conventional way publishers might have preferred. But that may be only part of the explanation for his love of Gissing. As I see it, Gissing writes very fine independent-minded women characters, and unusual women characters in literature are one of the things Murnane seems to value highly in his own reading: the 'odd' women who step outside the norm of their times; the 'odd' women who love reading and writing.

Yes, on reflection, I think that may well be it.