You need to sign in or sign up before continuing.

Take a photo of a barcode or cover

A review by ilse

The Pedant in the Kitchen by Julian Barnes

5.0

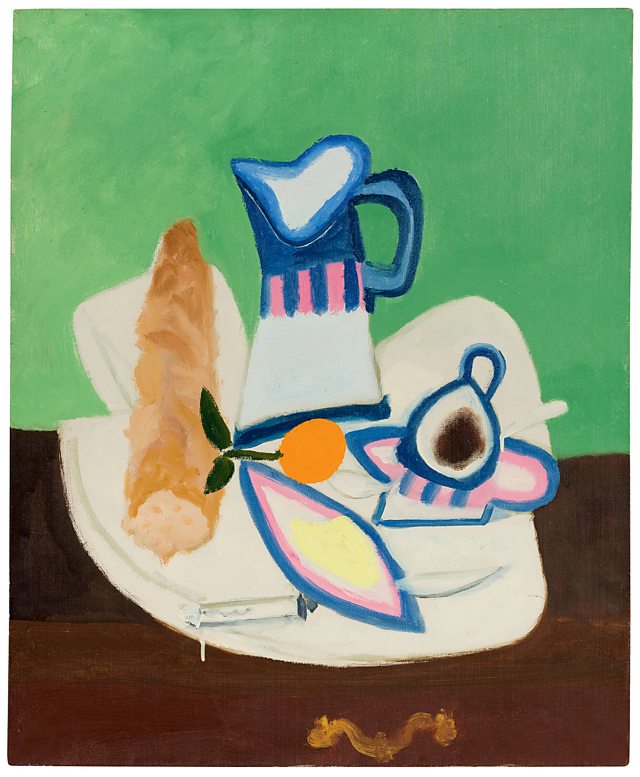

Cooking, a mundane or a frivolous subject? Neither for a self-proclaimed pedant cook as Julian Barnes, nor for me. Cooking (and writing about cooking) is a Serious Matter. Yet this quite hilarious collection of cooking columns which Barnes first published in The Guardian made me laugh out loud, perhaps ten times or more. For that reason alone, it is worth every star – or more – that can be given here, just because it is amusing and witty, winking complicitly at every domestic cook who isn’t or doesn’t feel a domestic god or goddess. Gracious self-mockery might keep one from ever aspiring such.

Where would you situate yourself on the cooking spectrum, are you a casual cook intuitively improvising meals together with fluke ingredients (trouvailles which tempted you during unorganised shopping) or do you stick to following recipes exactly as written and to careful meal planning? I would like to think of myself as comfortably in between those two opposites, but no, I could as well admit it: I might not be a pedantic, meticulous cook but I am certainly not an adventurous one, mostly clinging rather firmly to the recipe and the shopping list, trusting gullibly the recipe’s flavours will deliver and please as having stood the test of the expert creator of the recipe.

No wonder that quite a few of Barnes frustrations and wrath on unreliable cookbooks have been mine too. I couldn’t but chuckle at Barnes’s confession of his pedantry as a cook 'Why should a cookbook be less precise than a manual of surgery? (always assuming, as one nervously does, that manuals of surgery are indeed precise. Perhaps some of them sound just like cookbooks: ‘Sling a gout of anaesthetic down the tube, hack a chunk off the patient, watch the blood drizzle, have a beer with your mates, sew up the cavity…’). Why should a word in a recipe be less important than a word in a novel? One can lead to physical indigestion, the other to mental.'

If you ever found yourself bewildered about a detail in a recipe likewise this might be a book for you: 'The Pedant approaches a new recipe, however straightforward, with old anxieties: words flash at him like stop-signs. Is this recipe framed in this imprecise way because there is a happy latitude - or rather, a scary freedom - for interpretation; or because the writer isn't capable of expressing him- or herself more accurately? It start with simple words. How big is a ‘lump’, how voluminous is a ‘slug’ or a ‘gout’, when does a ‘drizzle’ become rain? Is a ‘cup’ and rough-and-ready generic term or a precise American measure? Why tell us to add a ‘wineglass’ of something, when wineglasses come in so many sizes? Or how about this instruction from Richard Olney: ‘Throw in as many strawberries as you can hold piled up in joined hands.’ I mean, really. Are we meant to write to the late Mr Olney’s executors and ask how big his hands were? What if children made this jam, or circus giants?’

Tell me how you cook and I will tell you who you are. Once musing on cooking styles I became enmeshed into a silly discussion whether such approach of recipe allegiance is masculine or feminine. As I happen to be a woman, my cooking was labelled suspiciously masculine, lacking the feminine virtue of confidence and creative freedom in the kitchen (unsurprisingly this reader’s cooking style was in unfavourable contrast to the evidently unattainable norm of la mama’s cuisine for He For Whom She Cooked as la mama didn’t need to rely on cookbooks to create the most amazing meals– isn’t such a common story?). Et alors? Perhaps this is so, as I spend lots of time browsing cookbooks to select recipes but use them as a manual, not merely for inspiration. Nor do I read their introductions or pay much attention to the tone in which the authorial cook addresses the domestic cook. A cookbook ideally has a precise list of ingredients(please spare me ‘handful’s or ‘dollops’ and pictures with green olives on it when not mentioned in the list or the recipe! Compare that to the precise instruction of twisting the pepper mill 80 times for a Bayaldi meant for the staff’s lunch in a renowned restaurant) and a clear step by step explanation what to do with them - a bit like the instructions in an Ikea manual (but simpler and not leaving one with too many superfluous or missing screws or plugs).

No exotic equipment or techniques should be needed, a kitchen knife, oven, stove and pots & pans have to do. Neither do I have any ambition on creating fancy pieces worth art nouveau on the plate (though I like to bring a nice splash of colour on the plates). Indications of cooking times I learned are ever misguiding, so I know I have to wait to try a new recipe when there is enough time to do so and the hungry creatures in the house can be fed before they get so tired of waiting that they devour the cook. Never believe the recipe which promises a quick and easy meal in about half an hour (more often than not the recipe takes three such halves an hour). Not slavishly following the recipe is just as important as following it, so Barnes had me nodding approvingly at his ‘No, We Won’t Do That’ chapter (add 3 lemons? Are you crazy, Jamie? The food is supposed to make my family smile, not cringe!).

Such down-to-earthiness doesn’t mean that cooking leaves me indifferent, far from that. The emotional and psychological landscape of the kitchen, as Barnes tongue-in cheek amply illustrates, is vast and profound. And as a bookish person, cookbooks make up a great part of that landscape.

Like Barnes I was a late-onset cook (overindulged I was by others doing the job for me), but once I started I found myself overnight turning into nothing less than cookbook fanatic, almost neurotically with my nose in a cookbook every day. Though I stayed out of mother’s kitchen apart from washing the dishes, oddly enough her cooking habits and style seem to be transferred to her daughter thoroughly. In the meantime mother and daughter collected a number of cookbooks and recipes fit to cook a different meal each day for several lifetimes. I was amused that our cooking kindredness showed also when calling her for advice the moment my son wanted us to have the traditional Christmas Eve dish he would have to miss because of the lockdown. Both with the same cookbook (of some well-known British cook) open on our lap on the page of the recipe, we had following conversation:

Me: mum, do you entirely stick to that recipe?

Mum: yes, of course I do, I follow it from a to z!

Me: and five potatoes are enough?

Mum: no, of course not, that is far too little for four people and especially for your ever hungry children!

Me: and one carrot?

Mum: oh, I use three instead of one.

Me: what about the cheese?

Mum: change it into Parmesan, or it will be far too bland!

Me: One egg?

Mum: No, at least one egg per person, such makes four! And double the amount of cream! And add fresh parsley!

Me: So, right, you entirely follow the recipe…thank you very much, mum!

Barnes’s take on forgotten vegetables – parsnip, Jerusalem artichoke, salsify, beetroot - reminded me of the revolt of my teenagers against them: there is a reason why people tried to forget about them, mummy dearest, why don’t you try to forget about ever serving them again too?

Unacquainted with British cookery culture or writing, none of Barnes’s favourite cookery writers (Elizabeth David, Jane Grigson and Marcella Hazan) did ring a bell with me (nor did the French Edouard de Pomiane) despite the rather decadent number of cookbooks that I collected over thirty years. This did not spoil the fun in the slightest and perhaps this little delightful and delicious book will prompt me to eventually have a peek into those introductions I so far ignored. Why not treat our cookbooks like our other books and respect them like good friends, deserving our full attention and openness to the less evident aspects of their personality?

Where would you situate yourself on the cooking spectrum, are you a casual cook intuitively improvising meals together with fluke ingredients (trouvailles which tempted you during unorganised shopping) or do you stick to following recipes exactly as written and to careful meal planning? I would like to think of myself as comfortably in between those two opposites, but no, I could as well admit it: I might not be a pedantic, meticulous cook but I am certainly not an adventurous one, mostly clinging rather firmly to the recipe and the shopping list, trusting gullibly the recipe’s flavours will deliver and please as having stood the test of the expert creator of the recipe.

No wonder that quite a few of Barnes frustrations and wrath on unreliable cookbooks have been mine too. I couldn’t but chuckle at Barnes’s confession of his pedantry as a cook 'Why should a cookbook be less precise than a manual of surgery? (always assuming, as one nervously does, that manuals of surgery are indeed precise. Perhaps some of them sound just like cookbooks: ‘Sling a gout of anaesthetic down the tube, hack a chunk off the patient, watch the blood drizzle, have a beer with your mates, sew up the cavity…’). Why should a word in a recipe be less important than a word in a novel? One can lead to physical indigestion, the other to mental.'

If you ever found yourself bewildered about a detail in a recipe likewise this might be a book for you: 'The Pedant approaches a new recipe, however straightforward, with old anxieties: words flash at him like stop-signs. Is this recipe framed in this imprecise way because there is a happy latitude - or rather, a scary freedom - for interpretation; or because the writer isn't capable of expressing him- or herself more accurately? It start with simple words. How big is a ‘lump’, how voluminous is a ‘slug’ or a ‘gout’, when does a ‘drizzle’ become rain? Is a ‘cup’ and rough-and-ready generic term or a precise American measure? Why tell us to add a ‘wineglass’ of something, when wineglasses come in so many sizes? Or how about this instruction from Richard Olney: ‘Throw in as many strawberries as you can hold piled up in joined hands.’ I mean, really. Are we meant to write to the late Mr Olney’s executors and ask how big his hands were? What if children made this jam, or circus giants?’

Tell me how you cook and I will tell you who you are. Once musing on cooking styles I became enmeshed into a silly discussion whether such approach of recipe allegiance is masculine or feminine. As I happen to be a woman, my cooking was labelled suspiciously masculine, lacking the feminine virtue of confidence and creative freedom in the kitchen (unsurprisingly this reader’s cooking style was in unfavourable contrast to the evidently unattainable norm of la mama’s cuisine for He For Whom She Cooked as la mama didn’t need to rely on cookbooks to create the most amazing meals– isn’t such a common story?). Et alors? Perhaps this is so, as I spend lots of time browsing cookbooks to select recipes but use them as a manual, not merely for inspiration. Nor do I read their introductions or pay much attention to the tone in which the authorial cook addresses the domestic cook. A cookbook ideally has a precise list of ingredients(please spare me ‘handful’s or ‘dollops’ and pictures with green olives on it when not mentioned in the list or the recipe! Compare that to the precise instruction of twisting the pepper mill 80 times for a Bayaldi meant for the staff’s lunch in a renowned restaurant) and a clear step by step explanation what to do with them - a bit like the instructions in an Ikea manual (but simpler and not leaving one with too many superfluous or missing screws or plugs).

No exotic equipment or techniques should be needed, a kitchen knife, oven, stove and pots & pans have to do. Neither do I have any ambition on creating fancy pieces worth art nouveau on the plate (though I like to bring a nice splash of colour on the plates). Indications of cooking times I learned are ever misguiding, so I know I have to wait to try a new recipe when there is enough time to do so and the hungry creatures in the house can be fed before they get so tired of waiting that they devour the cook. Never believe the recipe which promises a quick and easy meal in about half an hour (more often than not the recipe takes three such halves an hour). Not slavishly following the recipe is just as important as following it, so Barnes had me nodding approvingly at his ‘No, We Won’t Do That’ chapter (add 3 lemons? Are you crazy, Jamie? The food is supposed to make my family smile, not cringe!).

Such down-to-earthiness doesn’t mean that cooking leaves me indifferent, far from that. The emotional and psychological landscape of the kitchen, as Barnes tongue-in cheek amply illustrates, is vast and profound. And as a bookish person, cookbooks make up a great part of that landscape.

Like Barnes I was a late-onset cook (overindulged I was by others doing the job for me), but once I started I found myself overnight turning into nothing less than cookbook fanatic, almost neurotically with my nose in a cookbook every day. Though I stayed out of mother’s kitchen apart from washing the dishes, oddly enough her cooking habits and style seem to be transferred to her daughter thoroughly. In the meantime mother and daughter collected a number of cookbooks and recipes fit to cook a different meal each day for several lifetimes. I was amused that our cooking kindredness showed also when calling her for advice the moment my son wanted us to have the traditional Christmas Eve dish he would have to miss because of the lockdown. Both with the same cookbook (of some well-known British cook) open on our lap on the page of the recipe, we had following conversation:

Me: mum, do you entirely stick to that recipe?

Mum: yes, of course I do, I follow it from a to z!

Me: and five potatoes are enough?

Mum: no, of course not, that is far too little for four people and especially for your ever hungry children!

Me: and one carrot?

Mum: oh, I use three instead of one.

Me: what about the cheese?

Mum: change it into Parmesan, or it will be far too bland!

Me: One egg?

Mum: No, at least one egg per person, such makes four! And double the amount of cream! And add fresh parsley!

Me: So, right, you entirely follow the recipe…thank you very much, mum!

Barnes’s take on forgotten vegetables – parsnip, Jerusalem artichoke, salsify, beetroot - reminded me of the revolt of my teenagers against them: there is a reason why people tried to forget about them, mummy dearest, why don’t you try to forget about ever serving them again too?

Unacquainted with British cookery culture or writing, none of Barnes’s favourite cookery writers (Elizabeth David, Jane Grigson and Marcella Hazan) did ring a bell with me (nor did the French Edouard de Pomiane) despite the rather decadent number of cookbooks that I collected over thirty years. This did not spoil the fun in the slightest and perhaps this little delightful and delicious book will prompt me to eventually have a peek into those introductions I so far ignored. Why not treat our cookbooks like our other books and respect them like good friends, deserving our full attention and openness to the less evident aspects of their personality?