Take a photo of a barcode or cover

glenncolerussell's reviews

1456 reviews

The Sadness of Sex by Barry Yourgrau

If I were passing out literary awards, Barry Yourgrau wins the grand prize in the category of short-story writer with a vivid, outrageous, over-the-top imagination. And in this collection of ninety wacky, surreal micro-stories, Barry turns his extraordinary imaginative powers to the topic of Eros, or, in more plain language, that good ol’ trio to which we can all relate: love, lust, sex. To share a taste of what a reader will find in these pages, here are the openings sentences from five of my favorites:

POETRY

My girlfriend leaves me. I become so unhinged that I douse myself with flammable liquid and set myself on fire. I squat in an awkward hideous position on the sidewalk, bleating her name as I gasp in shock at what I’ve done. The chaos of flames envelopes me and the air about me trembles. Passersby scramble away in horror, their faces covered behind their arms. Their screaming gives way to the shrieking of sirens, I topple stiffly onto my side, crackling, unconscious.

POISON

I sit in a café in late morning. A girl hurries by. She gives a distracted smile. She’s quite pretty. In an appealing way. I stare hurriedly down at my coffee. I stir it with a spoon that trembles. A while later, she goes by again. I can’t stop myself: I look. She’s not pretty, I realize. She’s lovely! She’s utterly, wonderfully lovely! I groan and shift my shoes about on the floor and clutch the little round table with both hands. ------ Youtube video of this story with Barry as actor: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HaQ7nZBV0_s

SILVER ARROWS

I track a girl I fancy through the park. My little friend is helping. It’s slow going. The path veers up and down all the time and the stubby wings my friend sports are in fact just ornamental, so I’m forced to lug him about on my back, so he can keep up. The arrows in his quiver jab me in the neck. I have to put him down repeatedly to make him rearrange things. --------- Again, a Youtube video of this story with Barry acting as main character: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LwzFTW_A6J0

DARK HOSPITAL

I get a job at a hospital. It’s for victims of love. The wards are dingy and ill furnished, and the sufferings of the stricken in their squalor are truly heartrending. I’m overwhelmed. I have to stuff my ears with bathroom tissue to try to shut out the moans of anguish, the cries of longing, the desperate monologues into imaginary telephones that are never answered, never connected. Even semibuffered so, the tears often drip down my chin as I ply my mop sluggishly up and down the worn, crumbling corridors.

GOLDEN AGE

I have the good fortune to die and come back to life during far, far bygone days of a golden age. I find myself in the palm-crested precincts of some balmy South Seas isle. The locals are as benevolent as you could ever hope, physically glamorous and culturally on the simple side, and spotlessly clean of person. ------- Turns out, the young girls on the island lack one very important body part necessary for experiencing intense pleasure: a clitoris. But, no problem, Barry proposes a solution to the local old crone Shaman – sewing in a pearl. The results are fantastic beyond belief! Bizarre? From my own experience I can say that when you open yourself to your unconscious dream-world and then mold those crazy images into short prose, be prepared for some disturbing mindbenders and weird combinations you wouldn’t want to repeat in polite company.

Recognizing this psychoanalytic fact and in the spirit of Barry’s story of Golden Age, here is a short piece I wrote some years ago taken directly from one of my own vivid dreams. Apologies to any of my Goodreads freinds who might be offended - the muse sometimes speaks in ways that cause sheer pasta shock:

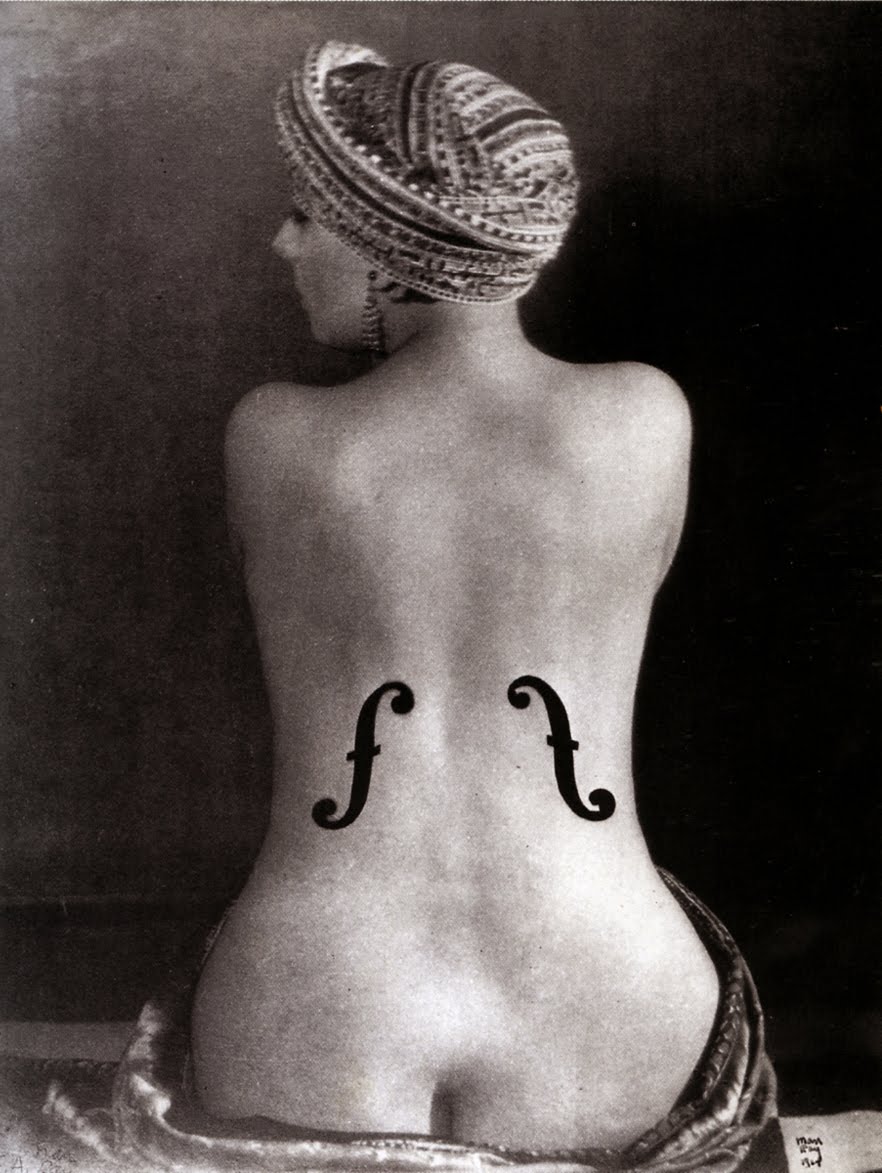

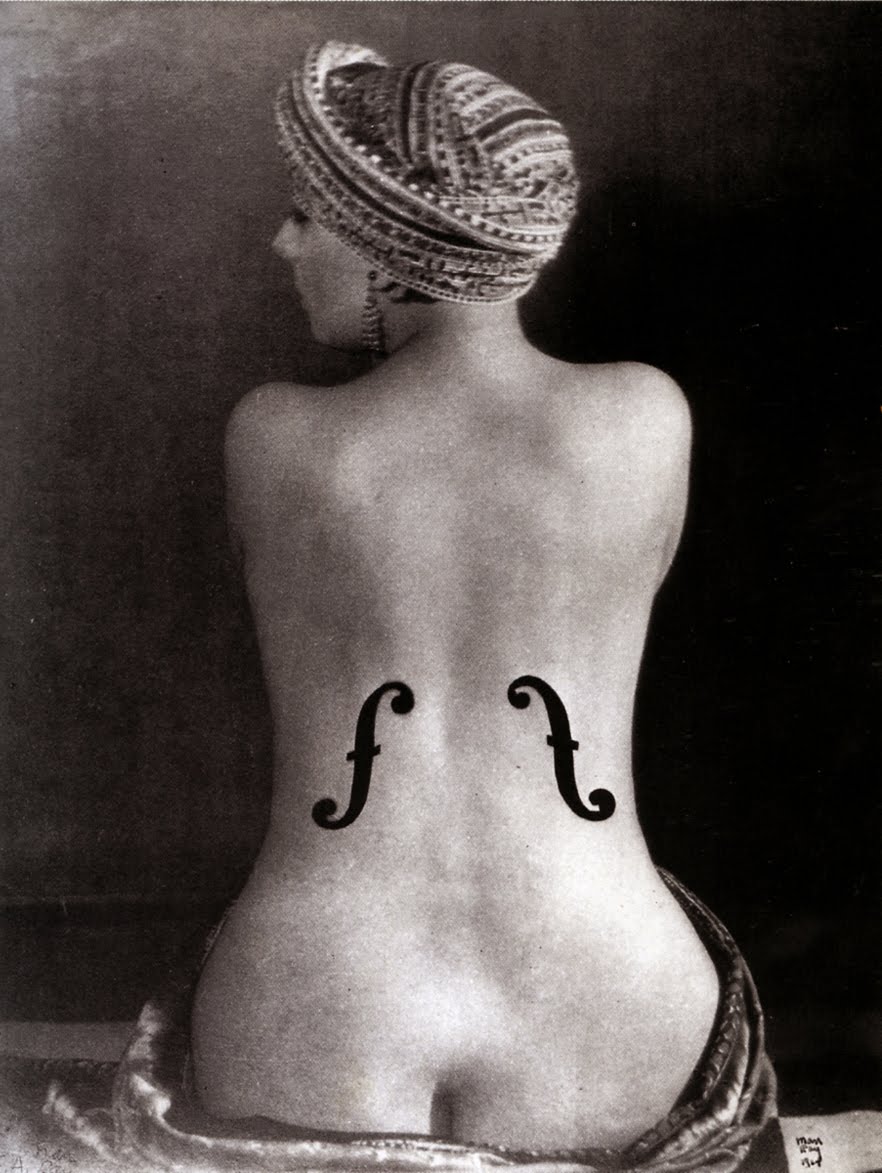

CONCERTO

On their feet, whistling, hooting, shouting, applauding, feet stomping in unison, the audience responds to a command performance by the soloist and orchestra of a cello concerto. There is a call, especially from the tuxedoed young men, for an encore! encore! But the cellist, a fetching young lady with long golden hair curling down over her shoulders and framing her fairy-tale princess face couldn’t play another note even if she wanted to. Anyone could see her energy is spent, her skin flushed and perspiring. All her skin, that is, for she is completely naked, having used her body for her cello, clitoris for bowstrings and the middle finger of her right hand for her bow.

5.0

If I were passing out literary awards, Barry Yourgrau wins the grand prize in the category of short-story writer with a vivid, outrageous, over-the-top imagination. And in this collection of ninety wacky, surreal micro-stories, Barry turns his extraordinary imaginative powers to the topic of Eros, or, in more plain language, that good ol’ trio to which we can all relate: love, lust, sex. To share a taste of what a reader will find in these pages, here are the openings sentences from five of my favorites:

POETRY

My girlfriend leaves me. I become so unhinged that I douse myself with flammable liquid and set myself on fire. I squat in an awkward hideous position on the sidewalk, bleating her name as I gasp in shock at what I’ve done. The chaos of flames envelopes me and the air about me trembles. Passersby scramble away in horror, their faces covered behind their arms. Their screaming gives way to the shrieking of sirens, I topple stiffly onto my side, crackling, unconscious.

POISON

I sit in a café in late morning. A girl hurries by. She gives a distracted smile. She’s quite pretty. In an appealing way. I stare hurriedly down at my coffee. I stir it with a spoon that trembles. A while later, she goes by again. I can’t stop myself: I look. She’s not pretty, I realize. She’s lovely! She’s utterly, wonderfully lovely! I groan and shift my shoes about on the floor and clutch the little round table with both hands. ------ Youtube video of this story with Barry as actor: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HaQ7nZBV0_s

SILVER ARROWS

I track a girl I fancy through the park. My little friend is helping. It’s slow going. The path veers up and down all the time and the stubby wings my friend sports are in fact just ornamental, so I’m forced to lug him about on my back, so he can keep up. The arrows in his quiver jab me in the neck. I have to put him down repeatedly to make him rearrange things. --------- Again, a Youtube video of this story with Barry acting as main character: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LwzFTW_A6J0

DARK HOSPITAL

I get a job at a hospital. It’s for victims of love. The wards are dingy and ill furnished, and the sufferings of the stricken in their squalor are truly heartrending. I’m overwhelmed. I have to stuff my ears with bathroom tissue to try to shut out the moans of anguish, the cries of longing, the desperate monologues into imaginary telephones that are never answered, never connected. Even semibuffered so, the tears often drip down my chin as I ply my mop sluggishly up and down the worn, crumbling corridors.

GOLDEN AGE

I have the good fortune to die and come back to life during far, far bygone days of a golden age. I find myself in the palm-crested precincts of some balmy South Seas isle. The locals are as benevolent as you could ever hope, physically glamorous and culturally on the simple side, and spotlessly clean of person. ------- Turns out, the young girls on the island lack one very important body part necessary for experiencing intense pleasure: a clitoris. But, no problem, Barry proposes a solution to the local old crone Shaman – sewing in a pearl. The results are fantastic beyond belief! Bizarre? From my own experience I can say that when you open yourself to your unconscious dream-world and then mold those crazy images into short prose, be prepared for some disturbing mindbenders and weird combinations you wouldn’t want to repeat in polite company.

Recognizing this psychoanalytic fact and in the spirit of Barry’s story of Golden Age, here is a short piece I wrote some years ago taken directly from one of my own vivid dreams. Apologies to any of my Goodreads freinds who might be offended - the muse sometimes speaks in ways that cause sheer pasta shock:

CONCERTO

On their feet, whistling, hooting, shouting, applauding, feet stomping in unison, the audience responds to a command performance by the soloist and orchestra of a cello concerto. There is a call, especially from the tuxedoed young men, for an encore! encore! But the cellist, a fetching young lady with long golden hair curling down over her shoulders and framing her fairy-tale princess face couldn’t play another note even if she wanted to. Anyone could see her energy is spent, her skin flushed and perspiring. All her skin, that is, for she is completely naked, having used her body for her cello, clitoris for bowstrings and the middle finger of her right hand for her bow.

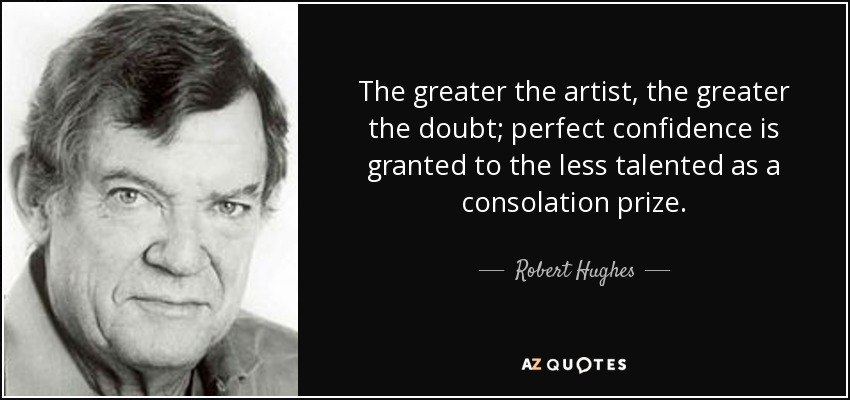

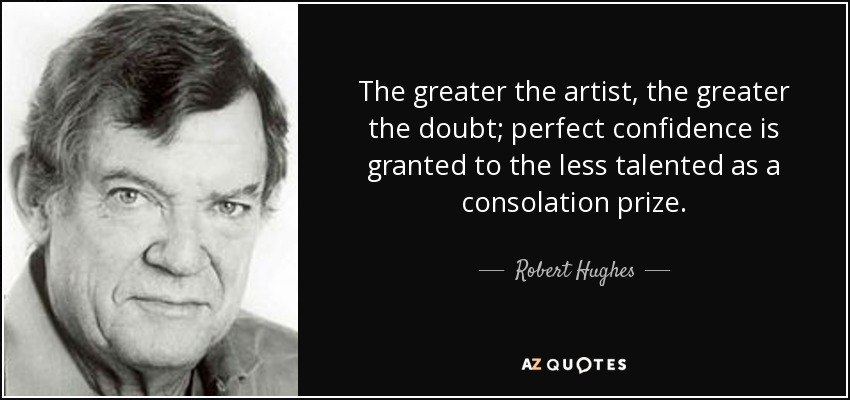

Nothing If Not Critical: Selected Essays on Art and Artists by Robert Hughes

Outstanding collection of nearly one hundred essays written in the 1980s, mostly for Time Magazine, on art and artists from Holbein, Goya, Degas, Whistler, van Gogh right up to the big names of the 50s, 60s, 70s and 80s, by the leading art critic at the time in America, outspoken, rough-and-ready tough-guy Robert Hughes (1938-2012).

If you are familiar with his 1970s documentary The Shock of the New, you know he has a hyper-perceptive eye for art as well as a thorough command of art history and cultural currents. If not, then these essays will introduce you to one of the freshest and liveliest voices ever to enter the house of art.

To provide a good strong taste of Robert Hughes’ style, below are quotes from his spirited essay on Andy Warhol, one of the few artists included in this collection that he really didn’t like.

Robert Hughes on Andy Warhol’s using everyday objects like soup cans, Brillo boxes or photos of Marilyn Monroe: “The tension this set up depended on the assumption, still in force in the sixties, that there was a qualitative difference between the perceptions of high art and the million daily diversions and instructions issued by popular culture. Since then, Warhol has probably done more than any other living artist to wear that distinction down, but while doing so, he has worn away the edge of his work.”

On Andy’s quest for celebrity: “Inspired by the example of Truman Capote, he went after publicity with the voracious singlemindedness of a feeding bluefish. And he got it in abundance, because the sixties in New York reshuffled and stacked the social deck: press and television, in their pervasiveness, constructed a kind of parallel universe in which the hierarchical orders of American society – vestiges, it was thought, but strong ones, and based on inherited wealth –were replaced by the new tyranny of the “interesting.” Its rule had to do with the rapid shift of style and image, with the assumption that all civilized life was discontinuous and worth only a short attention span: better to be Baby Jane Holzer than the Duchesse de Guermantes.”

On Andy and television: “Above all, the working-class kid who had spent so many thousands of hours gazing into the blue, anesthetizing glare of the TV screen, like Narcissus into his pool, realized that the cultural moment of the mid-sixties favored a walking void. Television was producing an affectless culture.”

On Andy’s mass produced art: “Thus his paintings, tremendously stylish in their rough silk-screening, full of slips, mimicked the dissociation of gaze and empathy induced by the mass media: the banal punch of tabloid newsprint, the visual jabber and bright sleazy color of TV, the sense of glut and anesthesia caused by both. Three dozen Elvises are better than one.”

On Andy as THE artist of the Ronald Reagan years: “How can one doubt that Warhol was delivered by Fate to be the Rubens of this administration, to play Bernini to Reagan’s Urban VIII? On the one hand, the shrewd old movie actor, void of ideas but expert at manipulation, projected into high office by the insuperable power of mass imagery and secondhand perception. On the other, the shallow painter who understood more about the mechanisms of celebrity than any of his colleagues, whose entire sense of reality was shaped, like Reagan’s sense of power, by the television tube. Each, in his way, coming on like Huck Finn; both obsessed with serving the interests of privilege. Together, they signify a new moment: the age of supply-side aesthetics.”

I read this Robert Hughes essay on Andy Warhol back when it was first published in 1982. Loved every word and really was on Hughes’ vibe since I recoil from anything smacking of mass culture, things like television, celebrity, glamour or glitz.

But then one spring afternoon in 1990 I had a shocking experience - I walked into a downtown New York City gallery and saw for the very first time original Andy Warhol silkscreens, one of Hermann Hesse and the other of Mickey Mouse.

I could almost not believe my eyes: the art was so stunningly beautiful and brimming over with vitality, it almost put me on my knees. Incredible. I couldn’t take my eyes off these silkscreens; I was riveted to the spot for a good long while.

For me, this experience underscored how the visual arts are ultimately a personal experience of standing before the original and using and trusting our eyes. Sure, art critics, even the great art critics, can speak about cultural and historical context, about the artist’s biography and the artist’s influences and intent, even offering comments and insights on specific works, but we are best putting theories and criticism aside when we engage with the work one-on-one. Who knows what magic may take place?

5.0

Outstanding collection of nearly one hundred essays written in the 1980s, mostly for Time Magazine, on art and artists from Holbein, Goya, Degas, Whistler, van Gogh right up to the big names of the 50s, 60s, 70s and 80s, by the leading art critic at the time in America, outspoken, rough-and-ready tough-guy Robert Hughes (1938-2012).

If you are familiar with his 1970s documentary The Shock of the New, you know he has a hyper-perceptive eye for art as well as a thorough command of art history and cultural currents. If not, then these essays will introduce you to one of the freshest and liveliest voices ever to enter the house of art.

To provide a good strong taste of Robert Hughes’ style, below are quotes from his spirited essay on Andy Warhol, one of the few artists included in this collection that he really didn’t like.

Robert Hughes on Andy Warhol’s using everyday objects like soup cans, Brillo boxes or photos of Marilyn Monroe: “The tension this set up depended on the assumption, still in force in the sixties, that there was a qualitative difference between the perceptions of high art and the million daily diversions and instructions issued by popular culture. Since then, Warhol has probably done more than any other living artist to wear that distinction down, but while doing so, he has worn away the edge of his work.”

On Andy’s quest for celebrity: “Inspired by the example of Truman Capote, he went after publicity with the voracious singlemindedness of a feeding bluefish. And he got it in abundance, because the sixties in New York reshuffled and stacked the social deck: press and television, in their pervasiveness, constructed a kind of parallel universe in which the hierarchical orders of American society – vestiges, it was thought, but strong ones, and based on inherited wealth –were replaced by the new tyranny of the “interesting.” Its rule had to do with the rapid shift of style and image, with the assumption that all civilized life was discontinuous and worth only a short attention span: better to be Baby Jane Holzer than the Duchesse de Guermantes.”

On Andy and television: “Above all, the working-class kid who had spent so many thousands of hours gazing into the blue, anesthetizing glare of the TV screen, like Narcissus into his pool, realized that the cultural moment of the mid-sixties favored a walking void. Television was producing an affectless culture.”

On Andy’s mass produced art: “Thus his paintings, tremendously stylish in their rough silk-screening, full of slips, mimicked the dissociation of gaze and empathy induced by the mass media: the banal punch of tabloid newsprint, the visual jabber and bright sleazy color of TV, the sense of glut and anesthesia caused by both. Three dozen Elvises are better than one.”

On Andy as THE artist of the Ronald Reagan years: “How can one doubt that Warhol was delivered by Fate to be the Rubens of this administration, to play Bernini to Reagan’s Urban VIII? On the one hand, the shrewd old movie actor, void of ideas but expert at manipulation, projected into high office by the insuperable power of mass imagery and secondhand perception. On the other, the shallow painter who understood more about the mechanisms of celebrity than any of his colleagues, whose entire sense of reality was shaped, like Reagan’s sense of power, by the television tube. Each, in his way, coming on like Huck Finn; both obsessed with serving the interests of privilege. Together, they signify a new moment: the age of supply-side aesthetics.”

I read this Robert Hughes essay on Andy Warhol back when it was first published in 1982. Loved every word and really was on Hughes’ vibe since I recoil from anything smacking of mass culture, things like television, celebrity, glamour or glitz.

But then one spring afternoon in 1990 I had a shocking experience - I walked into a downtown New York City gallery and saw for the very first time original Andy Warhol silkscreens, one of Hermann Hesse and the other of Mickey Mouse.

I could almost not believe my eyes: the art was so stunningly beautiful and brimming over with vitality, it almost put me on my knees. Incredible. I couldn’t take my eyes off these silkscreens; I was riveted to the spot for a good long while.

For me, this experience underscored how the visual arts are ultimately a personal experience of standing before the original and using and trusting our eyes. Sure, art critics, even the great art critics, can speak about cultural and historical context, about the artist’s biography and the artist’s influences and intent, even offering comments and insights on specific works, but we are best putting theories and criticism aside when we engage with the work one-on-one. Who knows what magic may take place?

Wearing Dad's Head by Barry Yourgrau

Many years ago when I first read this book of Barry Yourgrau’s collection of outlandishly imaginative surreal, fabulist micro-fictions, I thought his writing was too good to be true.

I just did complete another rereading and I can assure you – Barry’s book is, in fact, too good to be true. But, thanks to the blessings of the gods of our childhood dreams and our weird, hallucinogenic visions, we can read and appreciate his stories as well as marvel at his ability to turn a vivid, highly visual phrase.

Wearing Dad’s Head is one of Barry’s first published books and has a decidedly Freudian flavor, his mom and dad, especially his dad, having a predominant place in nearly all these wacky, sexually playful fictional snappers. I could write until I’m blue in my or my own dad’s face or my fingers turn blue and wash away in the bathtub à la one of Barry’s stories, so I will simply cite the opening of two of my favorite pieces.

UDDERS

I get involved in a game of strip poker. The others have somehow persuaded a cow to join in. The cow stands stupid and uncomfortable in the cigar smoke. My tablemates ply it with booze. It is decked out in a pathetic catalogue of bedroom apparel. Naturally it always plays a losing hand. It can’t manage with its garments, and everyone makes full use of the opportunity to handle it, in the name of assistance. I watch in disgust as a beefy bank-manager type fumbles with a lacy garter on the cow’s flank. His hands are trembling. “Will you look at those udders, will you look at those udders,” he keeps mumbling. His face is flushed crimson. ------ Here is a youtube video of Barry performing this story: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-QeVu...

MAGIC CARPET

My father arrives on a magic carpet. “Come on,” he says. Sitting cross-legged together, we lift magically into the air. We glide over the backyard. Our rectangular shadow passes over the sheets my mother is hanging up. She rushes out from them to the back gate. She wave at us and, shouts indistinctly. I lean over, excited and scared, and wave cautiously down to her. She signals frantically for me to come back. My father gives a lazy, sardonic laugh and opens and shuts a fat, much-ringed hand in farewell to my mother’s diminishing, tiny figure. She dwindles to a speck.

As a nod to my love of Barry’s stories and encouragement for any reader of this review to write some of your own imaginative micro-fiction, here is one of mine relating to my own boyhood and relationship with my father:

PARADE OF THE PAST

It’s back again, the same old dream, the one where I’m standing on the sidewalk of Main Street in the small shore town where I grew up and haven’t lived in decades. The street is filled with water – I might as well be in Venice – and here they come as if in a bizarre Fourth of July parade, floats or whatever they are, motoring down the watery street.

First there is a gigantic turtle, every bit as large as a truck, paddling with its head and the top of its shell above water, carrying on its back a band of giggling kids in bathing suits. The kids are obviously having a blast and they all wave to me.

Next, there’s a float labeled “Dads”, where a bunch of blue-collar, middle-age men I recognize from my youth, including my own dad, are sitting in easy chairs, surrounded by beautiful blonde, tanned, bathing beauties. The dads smile and wave to me, knowing they’ve never had it so good.

This passes and the third float comes into view. Here we have the people who tried their best to make my life hell, including the eighth-grade bully, an overbearing buffoon manager and a sinister coworker. Their float is really done up – balloons, swan figurines, streamers, glitter and a banner that reads: “The Bad Guys”. They are all smirking and, like the kids and the dads, wave to me until their float passes out of sight.

What makes this dream all the more puzzling is that I’m standing there, trying to figure out if this is really a holiday parade or the normal flow of weekday traffic. I’m inclined to think it’s nothing out of the ordinary, because, unlike a real parade, there are no spectators lining the streets; quite the contrary, I’m the only one present.

5.0

Many years ago when I first read this book of Barry Yourgrau’s collection of outlandishly imaginative surreal, fabulist micro-fictions, I thought his writing was too good to be true.

I just did complete another rereading and I can assure you – Barry’s book is, in fact, too good to be true. But, thanks to the blessings of the gods of our childhood dreams and our weird, hallucinogenic visions, we can read and appreciate his stories as well as marvel at his ability to turn a vivid, highly visual phrase.

Wearing Dad’s Head is one of Barry’s first published books and has a decidedly Freudian flavor, his mom and dad, especially his dad, having a predominant place in nearly all these wacky, sexually playful fictional snappers. I could write until I’m blue in my or my own dad’s face or my fingers turn blue and wash away in the bathtub à la one of Barry’s stories, so I will simply cite the opening of two of my favorite pieces.

UDDERS

I get involved in a game of strip poker. The others have somehow persuaded a cow to join in. The cow stands stupid and uncomfortable in the cigar smoke. My tablemates ply it with booze. It is decked out in a pathetic catalogue of bedroom apparel. Naturally it always plays a losing hand. It can’t manage with its garments, and everyone makes full use of the opportunity to handle it, in the name of assistance. I watch in disgust as a beefy bank-manager type fumbles with a lacy garter on the cow’s flank. His hands are trembling. “Will you look at those udders, will you look at those udders,” he keeps mumbling. His face is flushed crimson. ------ Here is a youtube video of Barry performing this story: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-QeVu...

MAGIC CARPET

My father arrives on a magic carpet. “Come on,” he says. Sitting cross-legged together, we lift magically into the air. We glide over the backyard. Our rectangular shadow passes over the sheets my mother is hanging up. She rushes out from them to the back gate. She wave at us and, shouts indistinctly. I lean over, excited and scared, and wave cautiously down to her. She signals frantically for me to come back. My father gives a lazy, sardonic laugh and opens and shuts a fat, much-ringed hand in farewell to my mother’s diminishing, tiny figure. She dwindles to a speck.

As a nod to my love of Barry’s stories and encouragement for any reader of this review to write some of your own imaginative micro-fiction, here is one of mine relating to my own boyhood and relationship with my father:

PARADE OF THE PAST

It’s back again, the same old dream, the one where I’m standing on the sidewalk of Main Street in the small shore town where I grew up and haven’t lived in decades. The street is filled with water – I might as well be in Venice – and here they come as if in a bizarre Fourth of July parade, floats or whatever they are, motoring down the watery street.

First there is a gigantic turtle, every bit as large as a truck, paddling with its head and the top of its shell above water, carrying on its back a band of giggling kids in bathing suits. The kids are obviously having a blast and they all wave to me.

Next, there’s a float labeled “Dads”, where a bunch of blue-collar, middle-age men I recognize from my youth, including my own dad, are sitting in easy chairs, surrounded by beautiful blonde, tanned, bathing beauties. The dads smile and wave to me, knowing they’ve never had it so good.

This passes and the third float comes into view. Here we have the people who tried their best to make my life hell, including the eighth-grade bully, an overbearing buffoon manager and a sinister coworker. Their float is really done up – balloons, swan figurines, streamers, glitter and a banner that reads: “The Bad Guys”. They are all smirking and, like the kids and the dads, wave to me until their float passes out of sight.

What makes this dream all the more puzzling is that I’m standing there, trying to figure out if this is really a holiday parade or the normal flow of weekday traffic. I’m inclined to think it’s nothing out of the ordinary, because, unlike a real parade, there are no spectators lining the streets; quite the contrary, I’m the only one present.

Disagreeable Tales by Léon Bloy

“I am the Parlor of Tarantulas!” he cried in a voice destined for the straightjacket, making the little factory women hasten their steps on the street.” Thus begins one of the short intense tales in this collection authored by French Decadent Léon Bloy (1846-1917).

Bloy despised the materialist, mechanized Americanization of European society and culture and yearned to connect with the spiritual dimensions of life, and thus, similar to fellow French Decadent Joris-Karl Huysmans, turned to Catholicism.

Subsequently, although these tales are soaked in the juice of perversion, cruelty or depravity, a good number have decidedly religious overtones. However, the short stories I particularly enjoy in this collection have nothing of religion. Thus, for the purpose of this review and to share a taste of Bloy’s finely tuned, highly polished prose, I will include several direct quotes in capsulizing two of my favorites:

THE PARLOR OF TARANTULAS

The narrator recalls as a young man in his twenties meeting a larger than life poet who wore his mane of shaggy, white hair like a lion. “His small face of smashed bricks staring out from under the snowflakes boiled more and baked redder each time one looked at him, a poetaster, altogether incapable of resigning himself to any attention, however distinguished in kind, that did not grant him first place, or, better yet, exclusive consideration.”

A reader has the impression Bloy is describing a flesh-and-blood embodiment of the late nineteenth century myth of the self-styled literary genius as madman, a cross between Edgar Allan Poe and Gérard de Nerval.

One evening the narrator accepts an invitation to visit this white-haired, flaming-eyed lion. Most unwise since he is forced to listen to every word of the muse-inspired poet’s five act play. We read, “At first the exercise did not displease me. The reader had a bizarre, gastralgic voice, which rose effortlessly from profound basses up to the sharpest, childlike tones. He spoke like this and truly played his drama, performing gestures that included falling to his knees in prayer when events so required. The curious spectacle amused me for an hour – that is, for as long as the first act. The unconscionable monster went so far as to take whole scenes from the top when he feared I might not have felt all their beauty; no word of admiring protest could restrain him. I had to swallow it whole, and it took to midnight.”

And after this five hour ordeal the narrator makes a move for the door. But no, there’s more, much more - the leonine artiste insists his young visitor listen to every word of his sonnets, all one thousand five hundred of them!

So, the visitor takes a seat once again, suppressing a groan of despair. And when the young narrator makes the mistake of falling asleep, he is woken by a cowbell. Then, to make sure there isn’t a repeat violation, the poet opens a drawer, pulls out a revolver, loads it carefully and places it on the table. The narrator tells us the torture lasted until sunrise. The tale ends with two more unexpected twists true to the spirit of French Decadence.

THE OLD MAN IN THE HOUSE

With signature Decadent spleen and humorous cynicism, Bloy begins his tale: “Ah! How Madame Alexandre could pride herself on her virtue! Just think! For three years she had tolerated him, that old swindler – that old string of stewed beef disgracing her house. You can just imagine that if he hadn’t been her father, she’d have long since slapped a return ticket on him: off to rot in the public infirmary!”

Bloy’s language has the acerbic bite of Friedrich Nietzsche or Maxim Gorky - as a matter of fact, with his beetling brow and pronounced moustache, Bloy even looks a bit like Nietzsche and Gorky.

And, that’s acerbic bite, as in hearing of dad’s fatherly touch when Madame Alexandre was just a mere girl: “Readied for field exercise from a tender age, at thirteen she assumed the distinguished position of a virginal oblate at the house of a Genevan millionaire esteemed for his virtue; this man called her his “angel of light” and perfected her ruination. Two years were all the debutante needed to finish off the Calvinist.”

And then when the old man is forced to live with his daughter to stay alive (she runs a house of prostitution), Bloy observes caustically, “Unaccustomed to commerce and no longer commanding his old tricks, he resembled an old fly without the vigor to make its way to a pile of excrement – a creature in which even the spiders took no interest.”

And then to underscore the scorn and cruelty with which Madame treated her old father, Bloy pens; “He was given a scarlet leotard with decorative braids and a kind of Macedonian cap which made him look like a Hungarian or a Pole facing adversity. Then, he received the title of count – Count Boutonski! – and he passed for a wreck decorated with glory, a ruin of the latest insurrection.”

Madame’s ruthlessness and brutality continues right up to the breaking point. No wonder Franz Kafka wrote of Léon Bloy, “His fire is nurtured by the dung-heap of modern times.”

(Thanks to Goodreads friend MJ Nicholls for bringing this fine collection to my attention.)

5.0

“I am the Parlor of Tarantulas!” he cried in a voice destined for the straightjacket, making the little factory women hasten their steps on the street.” Thus begins one of the short intense tales in this collection authored by French Decadent Léon Bloy (1846-1917).

Bloy despised the materialist, mechanized Americanization of European society and culture and yearned to connect with the spiritual dimensions of life, and thus, similar to fellow French Decadent Joris-Karl Huysmans, turned to Catholicism.

Subsequently, although these tales are soaked in the juice of perversion, cruelty or depravity, a good number have decidedly religious overtones. However, the short stories I particularly enjoy in this collection have nothing of religion. Thus, for the purpose of this review and to share a taste of Bloy’s finely tuned, highly polished prose, I will include several direct quotes in capsulizing two of my favorites:

THE PARLOR OF TARANTULAS

The narrator recalls as a young man in his twenties meeting a larger than life poet who wore his mane of shaggy, white hair like a lion. “His small face of smashed bricks staring out from under the snowflakes boiled more and baked redder each time one looked at him, a poetaster, altogether incapable of resigning himself to any attention, however distinguished in kind, that did not grant him first place, or, better yet, exclusive consideration.”

A reader has the impression Bloy is describing a flesh-and-blood embodiment of the late nineteenth century myth of the self-styled literary genius as madman, a cross between Edgar Allan Poe and Gérard de Nerval.

One evening the narrator accepts an invitation to visit this white-haired, flaming-eyed lion. Most unwise since he is forced to listen to every word of the muse-inspired poet’s five act play. We read, “At first the exercise did not displease me. The reader had a bizarre, gastralgic voice, which rose effortlessly from profound basses up to the sharpest, childlike tones. He spoke like this and truly played his drama, performing gestures that included falling to his knees in prayer when events so required. The curious spectacle amused me for an hour – that is, for as long as the first act. The unconscionable monster went so far as to take whole scenes from the top when he feared I might not have felt all their beauty; no word of admiring protest could restrain him. I had to swallow it whole, and it took to midnight.”

And after this five hour ordeal the narrator makes a move for the door. But no, there’s more, much more - the leonine artiste insists his young visitor listen to every word of his sonnets, all one thousand five hundred of them!

So, the visitor takes a seat once again, suppressing a groan of despair. And when the young narrator makes the mistake of falling asleep, he is woken by a cowbell. Then, to make sure there isn’t a repeat violation, the poet opens a drawer, pulls out a revolver, loads it carefully and places it on the table. The narrator tells us the torture lasted until sunrise. The tale ends with two more unexpected twists true to the spirit of French Decadence.

THE OLD MAN IN THE HOUSE

With signature Decadent spleen and humorous cynicism, Bloy begins his tale: “Ah! How Madame Alexandre could pride herself on her virtue! Just think! For three years she had tolerated him, that old swindler – that old string of stewed beef disgracing her house. You can just imagine that if he hadn’t been her father, she’d have long since slapped a return ticket on him: off to rot in the public infirmary!”

Bloy’s language has the acerbic bite of Friedrich Nietzsche or Maxim Gorky - as a matter of fact, with his beetling brow and pronounced moustache, Bloy even looks a bit like Nietzsche and Gorky.

And, that’s acerbic bite, as in hearing of dad’s fatherly touch when Madame Alexandre was just a mere girl: “Readied for field exercise from a tender age, at thirteen she assumed the distinguished position of a virginal oblate at the house of a Genevan millionaire esteemed for his virtue; this man called her his “angel of light” and perfected her ruination. Two years were all the debutante needed to finish off the Calvinist.”

And then when the old man is forced to live with his daughter to stay alive (she runs a house of prostitution), Bloy observes caustically, “Unaccustomed to commerce and no longer commanding his old tricks, he resembled an old fly without the vigor to make its way to a pile of excrement – a creature in which even the spiders took no interest.”

And then to underscore the scorn and cruelty with which Madame treated her old father, Bloy pens; “He was given a scarlet leotard with decorative braids and a kind of Macedonian cap which made him look like a Hungarian or a Pole facing adversity. Then, he received the title of count – Count Boutonski! – and he passed for a wreck decorated with glory, a ruin of the latest insurrection.”

Madame’s ruthlessness and brutality continues right up to the breaking point. No wonder Franz Kafka wrote of Léon Bloy, “His fire is nurtured by the dung-heap of modern times.”

(Thanks to Goodreads friend MJ Nicholls for bringing this fine collection to my attention.)

House Taken Over by Julio Cortázar

An outstanding collection of stories by the incomparable Julio Cortázar along with essays about Julio. My copy of this book is from my local library. If you can't locate this volume, please check out the more available collection entitled Blow-Up and Other Stories. As a way of sharing some Julio magic, I will focus on one of his frequently anthologized stories, a story I've read and reread over the years - House Taken Over. This story is available on-line following the following link: https://www.google.com/#q=house+taken+over+by+julio+cortazar

HOUSE TAKEN OVER

Eerie Recall: “We liked the house because, apart from its being old and spacious (in a day when old houses go down for a profitable auction of their construction materials), it kept the memories of great-grandparents, our paternal grandfather, our parents and the whole of childhood.” This very short story’s opening line packs so much punch: memories of great-grandparents, a grandfather and parents add the heavy weight of generations; the mention of memories echo the author’s own memories of a childhood spent ill in bed where he recounts a vivid dream of an unseen presence entering his boyhood home and taking over - all told, memories of childhood and older generations as ominous foreshadowing of events that will eventually unfold.

Elvio’s Story: Right at the outset, Elvio (the name I’ve given to our unnamed first-person narrator) provides the backstory: he and his sister Irene are pushing forty and have declined getting married so they can settle in together with “the unvoiced concept that the quiet, simple marriage of sister and brother was the indispensable end to the line established in the house by our grandparents.” Whoa, Elvio, hold on there! Are you sure your grandparents would have approved of you and your sister living as husband and wife? With this statement and others, along with his obsessive-compulsive need to clean house according to clockwork, I think we might be dealing with a less than reliable narrator, not to mention a less than mentally stable one.

Unnerved Narrator: Oddly, Elvio only wants to talk about the house and Irene since he tells us, self-effacingly, that he himself is not very important. Also, he alludes to how he and Irene need not work to earn a living since they are made rich through ownership of a farm.

So what do Irene and Elvio do all day after they spend their mornings cleaning house? Answer: he and his sister engage in those two sedentary pastimes of the idle rich: Irene knits and Elvio reads, usually books of French literature. They do this so as to, as Elvio puts it, 'kill time' (the story takes place prior to television and other in-home entertainment technologies).

And after Elvio explains the layout of the house in detail and how he and Irene usually do not go beyond a certain oak door, he makes a most peculiar observation: there is too much dust in the air in Buenos Aires. Really? Sounds like Elvio is obsessive-compulsive about cleanliness to the point of paranoia, a nasty combination as anyone knows who has ever had the misfortune to be around such a person. Sorry, Elvio, but all this reclusiveness, obsessive-compulsion and paranoia is beginning to sound just a bit creepy.

Turning Point: Halfway through the story there is a dramatic event shifting the entire tone, an event occurring one evening when Elvio decides to fix some mate. Here is how Julio Cortázar describes it: “I went down the corridor as far as the oak door, which was ajar, then turned into the hall toward the kitchen, when I heard something in the library or the dining room. The sound came through muted and indistinct, a chair being knocked over onto the carpet or the muffled buzzing of a conversation. At the same time, or a second later, I heard it as the end of the passage which led from those two rooms toward the door. I hurled myself against the door before it was too late and shut it, leaning on it with the weight of my body; luckily, the key was on our side; moreover, I ran the great bolt into place, just to be safe.”

Aftermath: Elvio informs Irene he had to shut the door to the back part of the house since they have taken over. Irene's reaction is telling: as a sister (and wife) she has joined her brother in his paranoia and fear. Their next days are painful, their daily routines are completely disrupted and brother and sister modify their life to accommodate the unseen presence that now inhabits half of their home.

You will have to read the story yourself to see how events unfold now that they are both living in the grip of fear. Again, Julio has written about the inspiration for his story, one of his earliest, as a fictionalization of one of his childhood nightmares. Julio also spoke about how presences from other dimensions, things like visions, hallucinations, dreams and apparitions would pop up at unexpected times, for example, he was sitting in the balcony of a theater prior to a concert when he saw fantastic creatures, small green globes, floating before his eyes. He subsequently took this specific hallucination and created his cronopios.

Coda: I mentioned I have reread this story many times. There is a good reason. Similar to Julio I have also had dreams of unseen presences. And similarly, in my own boyhood I had a number of creatures, both large and small, appear as hallucinations. As I’ve come to recognize, what is critical about such experiences is to deal with them creatively rather than giving into fear as brother and sister give into fear in House Taken Over.

5.0

An outstanding collection of stories by the incomparable Julio Cortázar along with essays about Julio. My copy of this book is from my local library. If you can't locate this volume, please check out the more available collection entitled Blow-Up and Other Stories. As a way of sharing some Julio magic, I will focus on one of his frequently anthologized stories, a story I've read and reread over the years - House Taken Over. This story is available on-line following the following link: https://www.google.com/#q=house+taken+over+by+julio+cortazar

HOUSE TAKEN OVER

Eerie Recall: “We liked the house because, apart from its being old and spacious (in a day when old houses go down for a profitable auction of their construction materials), it kept the memories of great-grandparents, our paternal grandfather, our parents and the whole of childhood.” This very short story’s opening line packs so much punch: memories of great-grandparents, a grandfather and parents add the heavy weight of generations; the mention of memories echo the author’s own memories of a childhood spent ill in bed where he recounts a vivid dream of an unseen presence entering his boyhood home and taking over - all told, memories of childhood and older generations as ominous foreshadowing of events that will eventually unfold.

Elvio’s Story: Right at the outset, Elvio (the name I’ve given to our unnamed first-person narrator) provides the backstory: he and his sister Irene are pushing forty and have declined getting married so they can settle in together with “the unvoiced concept that the quiet, simple marriage of sister and brother was the indispensable end to the line established in the house by our grandparents.” Whoa, Elvio, hold on there! Are you sure your grandparents would have approved of you and your sister living as husband and wife? With this statement and others, along with his obsessive-compulsive need to clean house according to clockwork, I think we might be dealing with a less than reliable narrator, not to mention a less than mentally stable one.

Unnerved Narrator: Oddly, Elvio only wants to talk about the house and Irene since he tells us, self-effacingly, that he himself is not very important. Also, he alludes to how he and Irene need not work to earn a living since they are made rich through ownership of a farm.

So what do Irene and Elvio do all day after they spend their mornings cleaning house? Answer: he and his sister engage in those two sedentary pastimes of the idle rich: Irene knits and Elvio reads, usually books of French literature. They do this so as to, as Elvio puts it, 'kill time' (the story takes place prior to television and other in-home entertainment technologies).

And after Elvio explains the layout of the house in detail and how he and Irene usually do not go beyond a certain oak door, he makes a most peculiar observation: there is too much dust in the air in Buenos Aires. Really? Sounds like Elvio is obsessive-compulsive about cleanliness to the point of paranoia, a nasty combination as anyone knows who has ever had the misfortune to be around such a person. Sorry, Elvio, but all this reclusiveness, obsessive-compulsion and paranoia is beginning to sound just a bit creepy.

Turning Point: Halfway through the story there is a dramatic event shifting the entire tone, an event occurring one evening when Elvio decides to fix some mate. Here is how Julio Cortázar describes it: “I went down the corridor as far as the oak door, which was ajar, then turned into the hall toward the kitchen, when I heard something in the library or the dining room. The sound came through muted and indistinct, a chair being knocked over onto the carpet or the muffled buzzing of a conversation. At the same time, or a second later, I heard it as the end of the passage which led from those two rooms toward the door. I hurled myself against the door before it was too late and shut it, leaning on it with the weight of my body; luckily, the key was on our side; moreover, I ran the great bolt into place, just to be safe.”

Aftermath: Elvio informs Irene he had to shut the door to the back part of the house since they have taken over. Irene's reaction is telling: as a sister (and wife) she has joined her brother in his paranoia and fear. Their next days are painful, their daily routines are completely disrupted and brother and sister modify their life to accommodate the unseen presence that now inhabits half of their home.

You will have to read the story yourself to see how events unfold now that they are both living in the grip of fear. Again, Julio has written about the inspiration for his story, one of his earliest, as a fictionalization of one of his childhood nightmares. Julio also spoke about how presences from other dimensions, things like visions, hallucinations, dreams and apparitions would pop up at unexpected times, for example, he was sitting in the balcony of a theater prior to a concert when he saw fantastic creatures, small green globes, floating before his eyes. He subsequently took this specific hallucination and created his cronopios.

Coda: I mentioned I have reread this story many times. There is a good reason. Similar to Julio I have also had dreams of unseen presences. And similarly, in my own boyhood I had a number of creatures, both large and small, appear as hallucinations. As I’ve come to recognize, what is critical about such experiences is to deal with them creatively rather than giving into fear as brother and sister give into fear in House Taken Over.

The Intuitive Journey and Other Works by Russell Edson

To celebrate the bright strawberry in the sky (what some people refer to as the sun), I'd like to share a number of my favorite Russell Edson pieces from this, my favorite Russell Edson book. As if slices of scrumptious strawberry pie, I hope you find the writing delectable.

TURTLES

Bales of turtles descend like floating oriental villages; and still they come, until the hills are only turtles, until there is no surface of the immediate earth that is not a turtle. They cover the trunks of trees, the branches. They are everywhere!

People are forced to shovel their way to the roads; forced to shovel out their beds at night; only to awaken from dreaming endlessly of turtles, covered with turtles.

People becomes so distracted they no longer remember how to speak, they do not know words anymore; only turtle . . . They stare, their heads askew, whispering, turtle, turtle, turtle . . .

THE GINGERBREAD WOMAN

An old woman wishes she could climb into her own basket, like a gingerbread woman, the one who would have naturally married the gingerbread man, had they been made with more detail in their genital areas.

. . . How nice to lie in a basket on a linen napkin, near a pot of jam and a chicken leg, being kissed by a gingerbread man . . . Summer shadow, summer light, branch sway . . . Delight!

IN THE FOREST

I was combing some long hair coming out of a tree . . .

I had noticed long hair coming out of a tree, and a comb on the ground by the roots of that same tree.

The hair and the comb seemed to belong together. not so much that the hair needed combing, but the reassurance of the comb being drawn through it . . .

I stood in the gloom and silence that many forests have in the pages of fiction, combing the thick womanly hair, the mammal-warm hair; even as the evening slowly took the forest into night . . .

Similar to the illustration at the very top, this woodcut print is by Russell Edson himself. As something of a bonus, here are the first several lines of the prose poem:

A ROOF WITH SOME CLOUDS BEHIND IT

A man is climbing what he thinks is the ladder of success.

He's got the idea, says father.

Yes, he seems to know the direction, says mother.

But do you realize that some men have gone quite the other way and brought up gold? says father.

Then you think he would do better in the earth? says mother.

I have a terrible feeling he's on the wrong ladder, says father.

But he's still in the right direction, isn't he? says mother.

Yes, but, you see, there seems to be only a roof with some clouds behind it at the top of the ladder, says father.

Hmmm, I never noticed that before, how strange. I wonder if that roof and those clouds realize that they're in the wrong place, says mother.

I don't think they're doing it on purpose, do you? says father.

No, probably just a thoughtless mistake, says mother.

5.0

To celebrate the bright strawberry in the sky (what some people refer to as the sun), I'd like to share a number of my favorite Russell Edson pieces from this, my favorite Russell Edson book. As if slices of scrumptious strawberry pie, I hope you find the writing delectable.

TURTLES

Bales of turtles descend like floating oriental villages; and still they come, until the hills are only turtles, until there is no surface of the immediate earth that is not a turtle. They cover the trunks of trees, the branches. They are everywhere!

People are forced to shovel their way to the roads; forced to shovel out their beds at night; only to awaken from dreaming endlessly of turtles, covered with turtles.

People becomes so distracted they no longer remember how to speak, they do not know words anymore; only turtle . . . They stare, their heads askew, whispering, turtle, turtle, turtle . . .

THE GINGERBREAD WOMAN

An old woman wishes she could climb into her own basket, like a gingerbread woman, the one who would have naturally married the gingerbread man, had they been made with more detail in their genital areas.

. . . How nice to lie in a basket on a linen napkin, near a pot of jam and a chicken leg, being kissed by a gingerbread man . . . Summer shadow, summer light, branch sway . . . Delight!

IN THE FOREST

I was combing some long hair coming out of a tree . . .

I had noticed long hair coming out of a tree, and a comb on the ground by the roots of that same tree.

The hair and the comb seemed to belong together. not so much that the hair needed combing, but the reassurance of the comb being drawn through it . . .

I stood in the gloom and silence that many forests have in the pages of fiction, combing the thick womanly hair, the mammal-warm hair; even as the evening slowly took the forest into night . . .

Similar to the illustration at the very top, this woodcut print is by Russell Edson himself. As something of a bonus, here are the first several lines of the prose poem:

A ROOF WITH SOME CLOUDS BEHIND IT

A man is climbing what he thinks is the ladder of success.

He's got the idea, says father.

Yes, he seems to know the direction, says mother.

But do you realize that some men have gone quite the other way and brought up gold? says father.

Then you think he would do better in the earth? says mother.

I have a terrible feeling he's on the wrong ladder, says father.

But he's still in the right direction, isn't he? says mother.

Yes, but, you see, there seems to be only a roof with some clouds behind it at the top of the ladder, says father.

Hmmm, I never noticed that before, how strange. I wonder if that roof and those clouds realize that they're in the wrong place, says mother.

I don't think they're doing it on purpose, do you? says father.

No, probably just a thoughtless mistake, says mother.

Monsieur de Phocas by Jean Lorrain

“The madness of the eyes is the lure of the abyss. Sirens lurk in the dark depths of the pupils as they lurk at the bottom of the sea, that I know for sure - but I have never encountered them, and I am searching still for the profound and plaintive gazes in whose depths I might be able, like Hamlet redeemed, to drown the Ophelia of my desire.”

― Jean Lorrain, Monsieur De Phocas

Is not Jean Lorrain’s aristocratic aesthete, Monsieur de Phocas, the decadent precursor of our ravishing glamor stars, dressed to the nines, diamonds sparkling, forever striking a pose in the celebrity spotlight? Perhaps so, but then again, as compared with Monsieur de Phocas, which diamond-studded celebrity could express themselves with such colorful, lush, eloquent language when describing their glamorous, oh-so-special lives?

By way of example, here is a diary entry where Phocas pens his reflections on a young exotic beauty: “And her eyes, what are her eyes like? Very beautiful – eyes which have looked long upon the sea. Eyes which have looked long upon the sea! Oh, the dear and distant eyes of sailors; the salt-water eyes of Bretons; the still-water eyes of mariners; the well-water eyes of Celts; the dreaming and infinitely transparent eyes of those who dwell beside rivers and lakes; the eyes which one sometimes rediscovers in the mountains, in the Tyrol and in the Pyrenes . . . eyes in which there are skies, vast expanses, dawns and twilights contemplated at length upon the open seas, the mountains or the plains . . . eyes into which have passed, and in which remain, so many horizons! Have I not encountered such eyes already, in my dreams?”

And Jean Lorrain’s novel can be seen as his own creative twist on Joris-Karl Huysmans’ À Rebours' (Against Nature). For example, similar to Huysmans’ main character, Des Esseintes, Monsieur de Phocas is nauseated by the modern, bourgeois, everyday cloth of humanity. Here are Phocas’ haughty, disdainful remarks whilst attending the theater: “The ugliness of that room, the ugliness of the whole audience! The costumes! The disgrace of that sheet-metal pomp which constitutes the ideal outfit of modern man: all those stove-pipes which enclose the legs, arms and torso of the clubman, who is strangled meanwhile by a collar of white porcelain. And the sadness: the greyness of all those faces, drained by the poor hygiene of city life and the abuse of alcohol; all the ravages of late nights and the anxieties of the rat race imprinted in nervous tics on all those fat and flabby faces . . . their pallor the colour of lard!”

For lovers of that cult favorite, that jewel of decadent literature, À Rebours, Jean Lorrain's novel is a treasure. I enjoyed reading every single luscious page since, unlike Huysmans’ classic, Monsier de Phocas is written in intimate first-person and the aesthetic abode of Phocas isn’t a personalized and aestheticized retreat house but the entire city of Paris.

And, of course, Phocas is the complete Decadent, suffering at various point from ennui (boredom), spleen (gloomy ire), impuissance (lack of energy) as well as intense highs and devastating lows fueled by opium and hashish, the exotic and the erotic, nightmares, masquerades, monsters and his association with a famous English painter of most peculiar temperament and murky disposition by the name of Claudius Ethal. We read: “That Claudius! When I am with that Englishman, I have the sensation of plunging into dirt and darkness: the tepid, flowing and suffocating more of my opium nightmare. When I listen to him the air becomes thick and his atrocious confidences stir up my basest instincts and dirtiest desires.”

Lastly, as a special bonus, not only does this book published by Dedalus included a 15-page introduction on the life and times of Jean Lorrain but there is also a 8-page essay on the novel itself, both authored by Francis Amery aka Brian Stapleford.

But, alas, I couldn’t conclude this review without one more quote from a novel bathed in the golden hues of Gustave Moreau, a novel written as if every sentence is meant to breath the poetry of Charles Baudelaire: “Black irises! It had to be black irises, and all that they implied, which greeted me on my return. Some unknown hand had caused these monstrous blooms to be distributed throughout the ground floor of my apartment in the Rue de Varenne. From the antechamber of the morning-room to the parlor every single room was beset by a disquieting flowering of darkness: a mute outburst of huge upstanding petals of greyish crêpe, like a host of bats set within the cups of flowers.”

5.0

“The madness of the eyes is the lure of the abyss. Sirens lurk in the dark depths of the pupils as they lurk at the bottom of the sea, that I know for sure - but I have never encountered them, and I am searching still for the profound and plaintive gazes in whose depths I might be able, like Hamlet redeemed, to drown the Ophelia of my desire.”

― Jean Lorrain, Monsieur De Phocas

Is not Jean Lorrain’s aristocratic aesthete, Monsieur de Phocas, the decadent precursor of our ravishing glamor stars, dressed to the nines, diamonds sparkling, forever striking a pose in the celebrity spotlight? Perhaps so, but then again, as compared with Monsieur de Phocas, which diamond-studded celebrity could express themselves with such colorful, lush, eloquent language when describing their glamorous, oh-so-special lives?

By way of example, here is a diary entry where Phocas pens his reflections on a young exotic beauty: “And her eyes, what are her eyes like? Very beautiful – eyes which have looked long upon the sea. Eyes which have looked long upon the sea! Oh, the dear and distant eyes of sailors; the salt-water eyes of Bretons; the still-water eyes of mariners; the well-water eyes of Celts; the dreaming and infinitely transparent eyes of those who dwell beside rivers and lakes; the eyes which one sometimes rediscovers in the mountains, in the Tyrol and in the Pyrenes . . . eyes in which there are skies, vast expanses, dawns and twilights contemplated at length upon the open seas, the mountains or the plains . . . eyes into which have passed, and in which remain, so many horizons! Have I not encountered such eyes already, in my dreams?”

And Jean Lorrain’s novel can be seen as his own creative twist on Joris-Karl Huysmans’ À Rebours' (Against Nature). For example, similar to Huysmans’ main character, Des Esseintes, Monsieur de Phocas is nauseated by the modern, bourgeois, everyday cloth of humanity. Here are Phocas’ haughty, disdainful remarks whilst attending the theater: “The ugliness of that room, the ugliness of the whole audience! The costumes! The disgrace of that sheet-metal pomp which constitutes the ideal outfit of modern man: all those stove-pipes which enclose the legs, arms and torso of the clubman, who is strangled meanwhile by a collar of white porcelain. And the sadness: the greyness of all those faces, drained by the poor hygiene of city life and the abuse of alcohol; all the ravages of late nights and the anxieties of the rat race imprinted in nervous tics on all those fat and flabby faces . . . their pallor the colour of lard!”

For lovers of that cult favorite, that jewel of decadent literature, À Rebours, Jean Lorrain's novel is a treasure. I enjoyed reading every single luscious page since, unlike Huysmans’ classic, Monsier de Phocas is written in intimate first-person and the aesthetic abode of Phocas isn’t a personalized and aestheticized retreat house but the entire city of Paris.

And, of course, Phocas is the complete Decadent, suffering at various point from ennui (boredom), spleen (gloomy ire), impuissance (lack of energy) as well as intense highs and devastating lows fueled by opium and hashish, the exotic and the erotic, nightmares, masquerades, monsters and his association with a famous English painter of most peculiar temperament and murky disposition by the name of Claudius Ethal. We read: “That Claudius! When I am with that Englishman, I have the sensation of plunging into dirt and darkness: the tepid, flowing and suffocating more of my opium nightmare. When I listen to him the air becomes thick and his atrocious confidences stir up my basest instincts and dirtiest desires.”

Lastly, as a special bonus, not only does this book published by Dedalus included a 15-page introduction on the life and times of Jean Lorrain but there is also a 8-page essay on the novel itself, both authored by Francis Amery aka Brian Stapleford.

But, alas, I couldn’t conclude this review without one more quote from a novel bathed in the golden hues of Gustave Moreau, a novel written as if every sentence is meant to breath the poetry of Charles Baudelaire: “Black irises! It had to be black irises, and all that they implied, which greeted me on my return. Some unknown hand had caused these monstrous blooms to be distributed throughout the ground floor of my apartment in the Rue de Varenne. From the antechamber of the morning-room to the parlor every single room was beset by a disquieting flowering of darkness: a mute outburst of huge upstanding petals of greyish crêpe, like a host of bats set within the cups of flowers.”

The Man Who Watched Trains Go By by Georges Simenon

This captivating page-turner is not a Detective Maigret novel but one Simenon termed roman durs, meaning uncomfortable or hard on the reader. With The Man Who Watched Trains Go By, each chapter begins with a brief epigraph, for example, the epigraph for Chapter 1 reads “In which Julius de Coster the Younger gets drunk at the Little-Saint George, and the impossible suddenly breaches the dykes of everyday life.”

Here's my choice of epigram for the book itself: "The Case of Kees Popinga, or how upon hearing shocking revelations, a well-to-do bourgeois bean counter goes completely berserk."

The first pages provide the setup: One icy December evening in the northern Dutch city of Groningen, forty-year-old family man Kees Popinga walks down to the dock to check on a cargo delivery he scheduled himself in his capacity as head clerk of an esteemed shipping firm. The enraged ship’s captain blasts him because the shipment did not arrived. Nonplussed, Kees strolls by a nearby pub only to see through the window, to his amazement, his boss, Julius de Coster, drinking at a table.

Julius waves for him to come in, and, between swigs of brandy, breezily tells Kees in so many words that he, Mr. Pop-in-ga, is Popinga the Poopstick, prime stooge, a ninny so blind he couldn’t see how he, Julius de Coster, has been embezzling, stealing and cheating for years, not to mention having extramarital sex with former employee Pamela, an attractive young lady everyone in the company, including Kees Popinga, dreamed of going to bed with.

Furthermore, Julius goes on, since he made a bad investment in sugar, the company is now bankrupt and not only will Popinga lose his job but also his life savings, thus his house and all other personal properties. Lowering his voice, Julius also informs Mr. Pop-in-ga that this is the very night he, the well-respected Julius de Coster, will be faking his own suicide and fleeing the country.

Poor Mr. Popinga! Nothing like having your well-ordered, comfortable Dutch bourgeois world come crashing down in a heap of rubble. And how, we may ask, does our staid, conservative shipping clerk react to this disaster? The next morning, he makes his first radical decision: to stay under the covers in bed.

What! Not go to the office, Kees? Mrs. Popinga is shocked, to say the least. Oh, yes, new world, new man. We read: “The important thing was that he felt completely at ease. This was the real him. Yes – this is how he should have acted all along.”

So, for the first time in his adult life Kees Popinga has a taste of tranquility and joy, a state free from agitation and constant worrying, what he recognizes as “the real him” – and for good reason: many the spiritual and philosophical tradition maintaining such a combination of tranquility and joy is, in fact, our birthright, our true nature. As existential psychologist R.D. Laing observed: “Our 'normal' 'adjusted' state is too often the abdication of ecstasy, the betrayal of our true potentialities.”

And then we read: “Kees had always dreamed of being something other than Kees Popinga. That explained why he was so completely the way he was – so completely Kees Popinga – and why he even overdid it. Because he knew that if he gave even an inch, nothing would stop him again.”

In other words, it’s all or nothing.- once the thin shell of rigid identity is even slightly cracked, the entire edifice breaks down. It’s as if, in his own clerkish way, Kees Popinga grasps R.D. Laing’s insight: “The condition of alienation, of being asleep, of being unconscious, of being out of one’s mind, is the condition of the normal man. Society highly values its normal man.”

Kees Popinga finally rouses himself from bed, shaves, showers, dresses and, without telling his wife of his plans, leaves his house and family forever, having resolved to also leave behind his identity as a "normal man."

What follows when he travels to Amsterdam to have sex with Pamela (Julius de Coster bragged about how he set the luscious Pamela up in a particularly posh hotel) and then on to Paris is a truly odd series of events, a story Luc Sante in his Introduction to this New York Review Books (NYRB) edition calls both galling and comic.

This Georges Simenon novel is a penetrating exploration into the psychology of personal identity. How far can Kees Popinga the bean counter free himself from his habit of counting beans (the former shipping clerk continually, almost obsessively, makes entries in a small red leather notebook he happens to find in his jacket pocket)? And how far will the consequences of his actions (for starters, he quite unintentionally kills Pamela) launch him into madness? If you are up for a quizzical existential tale by turns humorous and infuriating, this is your book.

Georges Simenon in Paris. Frequently, the author would observe people on the street, pick out an interesting face, usually a man, and imagine him dealing with an unexpected event that would strip him of all comfortable social clothing and push him to the limit.

5.0

This captivating page-turner is not a Detective Maigret novel but one Simenon termed roman durs, meaning uncomfortable or hard on the reader. With The Man Who Watched Trains Go By, each chapter begins with a brief epigraph, for example, the epigraph for Chapter 1 reads “In which Julius de Coster the Younger gets drunk at the Little-Saint George, and the impossible suddenly breaches the dykes of everyday life.”

Here's my choice of epigram for the book itself: "The Case of Kees Popinga, or how upon hearing shocking revelations, a well-to-do bourgeois bean counter goes completely berserk."

The first pages provide the setup: One icy December evening in the northern Dutch city of Groningen, forty-year-old family man Kees Popinga walks down to the dock to check on a cargo delivery he scheduled himself in his capacity as head clerk of an esteemed shipping firm. The enraged ship’s captain blasts him because the shipment did not arrived. Nonplussed, Kees strolls by a nearby pub only to see through the window, to his amazement, his boss, Julius de Coster, drinking at a table.

Julius waves for him to come in, and, between swigs of brandy, breezily tells Kees in so many words that he, Mr. Pop-in-ga, is Popinga the Poopstick, prime stooge, a ninny so blind he couldn’t see how he, Julius de Coster, has been embezzling, stealing and cheating for years, not to mention having extramarital sex with former employee Pamela, an attractive young lady everyone in the company, including Kees Popinga, dreamed of going to bed with.

Furthermore, Julius goes on, since he made a bad investment in sugar, the company is now bankrupt and not only will Popinga lose his job but also his life savings, thus his house and all other personal properties. Lowering his voice, Julius also informs Mr. Pop-in-ga that this is the very night he, the well-respected Julius de Coster, will be faking his own suicide and fleeing the country.

Poor Mr. Popinga! Nothing like having your well-ordered, comfortable Dutch bourgeois world come crashing down in a heap of rubble. And how, we may ask, does our staid, conservative shipping clerk react to this disaster? The next morning, he makes his first radical decision: to stay under the covers in bed.

What! Not go to the office, Kees? Mrs. Popinga is shocked, to say the least. Oh, yes, new world, new man. We read: “The important thing was that he felt completely at ease. This was the real him. Yes – this is how he should have acted all along.”

So, for the first time in his adult life Kees Popinga has a taste of tranquility and joy, a state free from agitation and constant worrying, what he recognizes as “the real him” – and for good reason: many the spiritual and philosophical tradition maintaining such a combination of tranquility and joy is, in fact, our birthright, our true nature. As existential psychologist R.D. Laing observed: “Our 'normal' 'adjusted' state is too often the abdication of ecstasy, the betrayal of our true potentialities.”

And then we read: “Kees had always dreamed of being something other than Kees Popinga. That explained why he was so completely the way he was – so completely Kees Popinga – and why he even overdid it. Because he knew that if he gave even an inch, nothing would stop him again.”

In other words, it’s all or nothing.- once the thin shell of rigid identity is even slightly cracked, the entire edifice breaks down. It’s as if, in his own clerkish way, Kees Popinga grasps R.D. Laing’s insight: “The condition of alienation, of being asleep, of being unconscious, of being out of one’s mind, is the condition of the normal man. Society highly values its normal man.”

Kees Popinga finally rouses himself from bed, shaves, showers, dresses and, without telling his wife of his plans, leaves his house and family forever, having resolved to also leave behind his identity as a "normal man."

What follows when he travels to Amsterdam to have sex with Pamela (Julius de Coster bragged about how he set the luscious Pamela up in a particularly posh hotel) and then on to Paris is a truly odd series of events, a story Luc Sante in his Introduction to this New York Review Books (NYRB) edition calls both galling and comic.

This Georges Simenon novel is a penetrating exploration into the psychology of personal identity. How far can Kees Popinga the bean counter free himself from his habit of counting beans (the former shipping clerk continually, almost obsessively, makes entries in a small red leather notebook he happens to find in his jacket pocket)? And how far will the consequences of his actions (for starters, he quite unintentionally kills Pamela) launch him into madness? If you are up for a quizzical existential tale by turns humorous and infuriating, this is your book.

Georges Simenon in Paris. Frequently, the author would observe people on the street, pick out an interesting face, usually a man, and imagine him dealing with an unexpected event that would strip him of all comfortable social clothing and push him to the limit.

Keep Your Shape by VIDMER, Robert Sheckley

“Exotic forms will undoubtedly be called for,” Pid went on. “And for that we have a special dispensation. But remember—any shape not assumed strictly in the line of duty is a foul, lawless device of The Shapeless One!” - Robert Sheckley, Keep Your Shape

Transformation, such an important theme from myths and legions around the world. Two powerful images come to mind. First, from Greek myth – the phoenix rising from the ashes, the legendary bird taking on new life from the death of its predecessor. The second is the following traditional tale from India about mistaken identity: There once was a lion cub raised by sheep. It began acting like a sheep, even began making baa baa baa sounds like a sheep. An adult lion came by and immediately understood what had happened. She grabbed the cub by the fur and carried it to a lake where it could peer into the water and see it wasn’t a sheep at all; it was a lion.

How I wish I knew about Robert Sheckley’s Keep Your Shape in my early teens. I’m sure it would have instantly become my all-time favorite story. Such an action-packed, electrifying tale on the power of transformation. I can see my toehead thirteen year old self reading it over and over, even daydreaming about it, and maybe even committing a few lines to memory.

Sheckley frames his tale thusly: what happened to the twenty previous Grom missions to planet Earth remains a mystery. Pid the Pilot heads mission number twenty-one. Pid has two assistants, Gur the Detector and Ilg the radioman, both chosen for the ingenuity and resourcefulness but, unfortunately for the Grom powers that be, both are among the lower Grom castes prone to shaplessness. Very important for those Grom leaders since every creature on Grom, amorphous by nature, is given a shape prescribed by tradition and enforced by discipline and a sense of duty.

Pid takes great pride in being a pilot, following in the footsteps of his father, gradfather, right on back to beginning of time. After Pid pilots a successful landing on Earth, the crew is now ready to take the first step in fulfilling their mission – prepare for a full Grom military attack by linking the power from one of Earth’s atomic plants to a power source back on Grom.

Quickly the unexpected happens: there exists on Earth something Pid, Gur and Ilg experience for the first time: freedom. More specifically, freedom to change shape. Gur and Ilg take to their new found freedom immediately. What do you expect from the lower classes?! Pid is more conflicted – its tradition and duty versus freedom and joy. One of the most charming science fiction tales ever written. Drats! I wish I read this back as a kid.

KEEP YOUR SHAPE is available online: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/32346

and a lively audio of the story is also available: http://escapepod.org/2014/07/21/ep455-keep-shape/

American science fiction author Robert Sheckley, 1928 - 2005

5.0

“Exotic forms will undoubtedly be called for,” Pid went on. “And for that we have a special dispensation. But remember—any shape not assumed strictly in the line of duty is a foul, lawless device of The Shapeless One!” - Robert Sheckley, Keep Your Shape

Transformation, such an important theme from myths and legions around the world. Two powerful images come to mind. First, from Greek myth – the phoenix rising from the ashes, the legendary bird taking on new life from the death of its predecessor. The second is the following traditional tale from India about mistaken identity: There once was a lion cub raised by sheep. It began acting like a sheep, even began making baa baa baa sounds like a sheep. An adult lion came by and immediately understood what had happened. She grabbed the cub by the fur and carried it to a lake where it could peer into the water and see it wasn’t a sheep at all; it was a lion.

How I wish I knew about Robert Sheckley’s Keep Your Shape in my early teens. I’m sure it would have instantly become my all-time favorite story. Such an action-packed, electrifying tale on the power of transformation. I can see my toehead thirteen year old self reading it over and over, even daydreaming about it, and maybe even committing a few lines to memory.

Sheckley frames his tale thusly: what happened to the twenty previous Grom missions to planet Earth remains a mystery. Pid the Pilot heads mission number twenty-one. Pid has two assistants, Gur the Detector and Ilg the radioman, both chosen for the ingenuity and resourcefulness but, unfortunately for the Grom powers that be, both are among the lower Grom castes prone to shaplessness. Very important for those Grom leaders since every creature on Grom, amorphous by nature, is given a shape prescribed by tradition and enforced by discipline and a sense of duty.