Take a photo of a barcode or cover

halfextinguishedthoughts's Reviews (33)

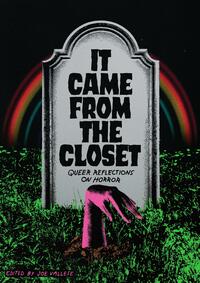

I love this so much. Good, varied, intimate (and spooky) stories about being queer and trans as felt and lived through horror movies. I listened to this but would love to go back and read through the physical book.

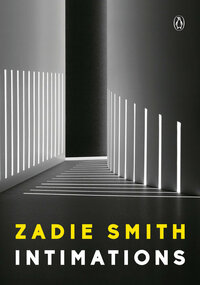

Intimations was a mixed bag for me. Some of the antecdotes were interesting and hard-hitting and others, not so much. This is my first book by Smith and wasn’t sure what to excpect. Some are saying it’s outdated but I think this is not true. Instead, I think this is a moment in time, and one we need to talk about more. There’s a quote on the back that stuck with me: “When an unfamiliar world arrives, what does it reveal about the world that came before it?” I think some of these essays do a good job exploring that question.

There’s also a strange bit about Palestine here I wasn’t quite sure what to make of and after some research it seems the author has a bit of a contradictory opinions on the language surrounding the genocide. I need to do more research on this.

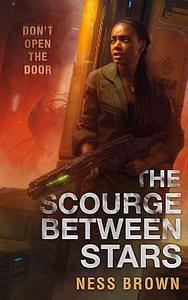

I found this a bit hard to follow both story wise and from a character perspective. The twist at the end was good but it felt too short.

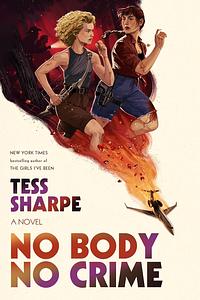

Adventure filled, romantic, and so much fun! I had a blast with this one.

A book of plenty. A book stuffed full of descriptions; one list after another. Yet, like the characters there's an emptiness there, the gorgeous lily's yet only in a plastic water bottle. This felt like a strange meditation to me, one I wouldn't want to linger but felt all to relevant while reading.

A look into women’s roles at a more macro level and, more specifically, as mothers. This has really intentional imagery that brings greater depth to the story. It did slow its pace towards the end but Yu Ling’s narration kept me interested. I enjoyed this read.

Blew through this. At times felt a bit abstract/ hard to picture what was happening to our mc, Vern, but there was such ferocious, tender moments here. Solomon has such a poignant writing style.

Tender and ferocious. Excellent writing. I went through phases of loving this and phases of feeling at a distance from the text. Chang always had something interesting to say though.

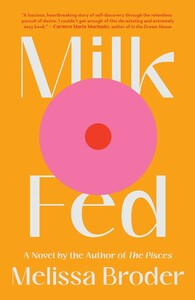

Strong start and sort of bobbed along after. Check the tw but it navigated ed in what felt like a realistic way. Author tries to make a point opposing Israel and has the mc argue with Zionist characters but didn’t come out the strongest. Free Palestine!