Take a photo of a barcode or cover

kevin_shepherd's Reviews (563)

The American Dream

“A big, sandy-haired man held his daughter on his shoulders, showing her the Statue of Liberty. I would never know what this statue meant to others, she had always been an ugly joke for me. And the American flag was flying from the top of the ship, above my head. I had seen the French flag drive the French into the most unspeakable frenzies, I had seen the flag which was nominally mine used to dignify the vilest purposes: now I would never, as long as I lived, know what others saw when they saw a flag.”

Faith, Country, and the color of your skin

“…everyone’s life begins on a level where races, armies, and churches stop. And yet everyone’s life is always shaped by races, churches and armies; races, churches, armies menace, and have taken many lives.”

In reading Baldwin, I am reminded of an old photo I once saw. A snapshot of a small crowd posing on an old bridge. There are men and women. There are summer frocks and straw hats and a few smiles. Beneath the bridge there are two people, a man and a woman, suspended by ropes. The people standing on the bridge are all white, the people hanging beneath the bridge are not.

This, my introduction to the works of James Baldwin, has left me somewhat speechless. His prose is minimal and simple and yet so powerful that you can almost smell the sweat and taste the blood. There is no trace of sensationalism in his words, just a stark, matter-of-fact narrative that hollows out your insides.

“A big, sandy-haired man held his daughter on his shoulders, showing her the Statue of Liberty. I would never know what this statue meant to others, she had always been an ugly joke for me. And the American flag was flying from the top of the ship, above my head. I had seen the French flag drive the French into the most unspeakable frenzies, I had seen the flag which was nominally mine used to dignify the vilest purposes: now I would never, as long as I lived, know what others saw when they saw a flag.”

Faith, Country, and the color of your skin

“…everyone’s life begins on a level where races, armies, and churches stop. And yet everyone’s life is always shaped by races, churches and armies; races, churches, armies menace, and have taken many lives.”

In reading Baldwin, I am reminded of an old photo I once saw. A snapshot of a small crowd posing on an old bridge. There are men and women. There are summer frocks and straw hats and a few smiles. Beneath the bridge there are two people, a man and a woman, suspended by ropes. The people standing on the bridge are all white, the people hanging beneath the bridge are not.

This, my introduction to the works of James Baldwin, has left me somewhat speechless. His prose is minimal and simple and yet so powerful that you can almost smell the sweat and taste the blood. There is no trace of sensationalism in his words, just a stark, matter-of-fact narrative that hollows out your insides.

“The so-called Negro are childlike people - you’re like children. No matter how old you get, or how bold you get, or how wise you get, or how rich you get, or how educated you get, the white man still calls you what? Boy! Why, you are a child in his eyesight! And you ARE a child. Anytime you have to let another man set up a factory for you and you cannot set up a factory for yourself, you’re a child; anytime another man has to open up businesses for you and you cannot open up businesses for yourself and your people, you’re a child; anytime another man sets up schools and you don’t know how to set up your own schools, you’re a child. Because a child is someone who sits around and waits for his father to do for him what he should be doing for himself, or what he is too young to do for himself, or what he is too dumb to do for himself. So the white man, knowing that here in America all the Negro has done - I hate to say it, but it’s the truth - all you and I have done is build churches and let the white man build factories. You and I build churches and let the white man build schools. You and I build churches and let the white man build up everything for himself. Then after you build the church you have to go and beg the white man for a job, and beg the white man for some education. Am I right or wrong? Do you see what I mean? It’s too bad but it’s true. And it’s history.”

One of the greatest orators of all time, Malcolm X asked all the right questions. He could make the scales not just fall away but fly away from your eyes. My problem with Malcolm’s early ideology, and I say this with a great deal of reverence and respect for the man, is that he traded one yoke of lies and deceptions for another. He could clearly see the hypocrisy of christianity yet he fell headlong - hook, line and sinker - for a false prophet of islam. And just as he was figuring that out, BECAUSE he was figuring that out, he was assassinated.

One of the greatest orators of all time, Malcolm X asked all the right questions. He could make the scales not just fall away but fly away from your eyes. My problem with Malcolm’s early ideology, and I say this with a great deal of reverence and respect for the man, is that he traded one yoke of lies and deceptions for another. He could clearly see the hypocrisy of christianity yet he fell headlong - hook, line and sinker - for a false prophet of islam. And just as he was figuring that out, BECAUSE he was figuring that out, he was assassinated.

Here are fourteen short stories that throw light on that ominous intersection of Black and White. Langston Hughes wrote with amazing clarity and purpose. His absorbing fiction reveals the abhorrent realities of the Jim Crow South and reanimates a shameful era of history that none of us should ever, ever forget.

“The French people have placed the negro soldier in France on an equality with the white man, and it has gone to their heads.” ~Woodrow Wilson, 1919

Malcolm X was a brilliant, courageous badass who saw American Christianity as an obstacle to equality and justice...

“[Malcolm] launched a frontal assault upon the New Testament promise of the “hereafter” so widely accepted by Negroes, religious or not. Malcolm flatly dismissed all chances of human postmortem reward, proclaiming that there would be “no Heaven beyond the grave.” A few in the audience gasped. American Negroes, “the lost sheep,” Malcolm thundered, would progress only when they forsook the Christian yearning for the hereafter and devote themselves to Muslim concerns for the right-down here and now.” (pg 314)

And why not rebel against the same articles of faith that were cited time and time again to justify slavery? Why not rebel against the same scripture that was interpreted as “proof” of white supremacy? Why not throw off the yoke that helped maintain an unjust status quo?

“...Malcolm flogged Christianity up hill and down dale... he dismissed organized church enterprises as an insidious confidence game with a sad history of duping poor people the world over. He blistered high-living clergy for dressing in splendor while their parishioners struggled to put pork chops and collard greens on the table.” (pg 399)

Malcolm saw clearly that the Bible had become a tool of oppression, an instrument of hardship, used to elevate one race and subjugate another. What he couldn’t see, at least not until the twilight of his very short life, was that false prophets are everywhere...

“The spartan Malcolm could no longer suppress the realization that, like the Christian ministers he attacked, [Elijah] Muhammad and his Royal Family engaged in conspicuous consumption while presiding over a struggling, low-income, working-class flock.” (pg 399)

Let’s face it, we all know how this story ends. Malcolm, like Abraham, like John, like Martin, like Bobby, didn’t get to write the ending of his own story. Somebody else wrote it for him.

Authors Les and Tamara Payne document the evolution of an extraordinary life, and they do it beautifully and without undue reverence. Five stars.

Personal Note: My high regard for Malcolm always feels a little like cultural appropriation. I tread lightly out of respect and because I am aware that I will never know what it is like to grow up as a black man in America. All I can say is that I am striving to better understand that experience. -Kevin

Malcolm X was a brilliant, courageous badass who saw American Christianity as an obstacle to equality and justice...

“[Malcolm] launched a frontal assault upon the New Testament promise of the “hereafter” so widely accepted by Negroes, religious or not. Malcolm flatly dismissed all chances of human postmortem reward, proclaiming that there would be “no Heaven beyond the grave.” A few in the audience gasped. American Negroes, “the lost sheep,” Malcolm thundered, would progress only when they forsook the Christian yearning for the hereafter and devote themselves to Muslim concerns for the right-down here and now.” (pg 314)

And why not rebel against the same articles of faith that were cited time and time again to justify slavery? Why not rebel against the same scripture that was interpreted as “proof” of white supremacy? Why not throw off the yoke that helped maintain an unjust status quo?

“...Malcolm flogged Christianity up hill and down dale... he dismissed organized church enterprises as an insidious confidence game with a sad history of duping poor people the world over. He blistered high-living clergy for dressing in splendor while their parishioners struggled to put pork chops and collard greens on the table.” (pg 399)

Malcolm saw clearly that the Bible had become a tool of oppression, an instrument of hardship, used to elevate one race and subjugate another. What he couldn’t see, at least not until the twilight of his very short life, was that false prophets are everywhere...

“The spartan Malcolm could no longer suppress the realization that, like the Christian ministers he attacked, [Elijah] Muhammad and his Royal Family engaged in conspicuous consumption while presiding over a struggling, low-income, working-class flock.” (pg 399)

Let’s face it, we all know how this story ends. Malcolm, like Abraham, like John, like Martin, like Bobby, didn’t get to write the ending of his own story. Somebody else wrote it for him.

Authors Les and Tamara Payne document the evolution of an extraordinary life, and they do it beautifully and without undue reverence. Five stars.

Personal Note: My high regard for Malcolm always feels a little like cultural appropriation. I tread lightly out of respect and because I am aware that I will never know what it is like to grow up as a black man in America. All I can say is that I am striving to better understand that experience. -Kevin

Toni Morrison doesn’t just tell a story, she illuminates a neighborhood, populates it with souls, then sets it in motion. There is an almost immediate intimacy with her characters that puts a reader at ease. I didn’t have to stop and ask myself who I needed to be in order to connect with this, I just did.

“Jesus, they say, rose after three days. Emmett did too. After his abductors tortured and killed him, they tied a seventy-pound cotton gin fan around what was left of his neck. Wanting no one to know how much he’d suffered for the sins of his nation, they tossed his remains into the Tallahatchie River. No doubt his were not the only bones there. Find any ground where black people toiled in the Jim Crow South, any body of water that bore witness to their labors, sift the soil, dredge the depths, and you are bound to find some bones.”

Readers, like writers, need room to fail.

It’s one thing for me, one of the whitest guys you’ll ever meet, to read books about systemic American racism; it’s something altogether different to write about those books from a perspective of white privilege. I feel as though I must tread ever so carefully because I have never inhabited that space.

Yes, authors like Jabari Asim and Michelle Alexander and Cornel West inspire me, but not to just sit here and type. I can’t read Asim’s words and then do nothing more than tap out a glowing GoodReads review hoping that my friends will read it and affirm how non-racist I am. We should all want to do more than just pat each other on the back, right? Maybe we need to kick each other in the butt once in a while and say ‘Get out there and march!’ or ‘Get out there and show support!’ or (most importantly) ‘Get out there and VOTE!’

“I’m so tired of waiting,

Aren’t you,

For the world to become good

And beautiful and kind?”

~Langston Hughes, “Tired”

Readers, like writers, need room to fail.

It’s one thing for me, one of the whitest guys you’ll ever meet, to read books about systemic American racism; it’s something altogether different to write about those books from a perspective of white privilege. I feel as though I must tread ever so carefully because I have never inhabited that space.

Yes, authors like Jabari Asim and Michelle Alexander and Cornel West inspire me, but not to just sit here and type. I can’t read Asim’s words and then do nothing more than tap out a glowing GoodReads review hoping that my friends will read it and affirm how non-racist I am. We should all want to do more than just pat each other on the back, right? Maybe we need to kick each other in the butt once in a while and say ‘Get out there and march!’ or ‘Get out there and show support!’ or (most importantly) ‘Get out there and VOTE!’

“I’m so tired of waiting,

Aren’t you,

For the world to become good

And beautiful and kind?”

~Langston Hughes, “Tired”

“Give me a .45 caliber, then I’ll sing ‘We Shall Overcome.’ ...the only real power in this society comes from either the ballot or the bullet.” ~MX

Choose the ballot.

When it came to assessing white America, Malcolm was a pessimist. And who could blame him? 1492 to 1965 was a LONG time for a country to recognize its obvious shortcomings and still fail to correct course. If 400+ years weren’t enough, what time frame was plausible? The prognosis was grim in 1965 and frankly, half a century later, it’s still pretty bleak. If Malcolm, who was quite possibly the most honest, the most unselfish, the most badass MF to ever lift his voice in dissent, died ambivalent about American democracy, then what’s the best any of us can hope for?

*Bernard Aquina Doctor’s biography of Malcolm X is brief but powerful. His artwork and text convey the essence of this important, controversial icon in a manner that should appeal to a youthful demographic, as well as broken down old history buffs like me.

Choose the ballot.

When it came to assessing white America, Malcolm was a pessimist. And who could blame him? 1492 to 1965 was a LONG time for a country to recognize its obvious shortcomings and still fail to correct course. If 400+ years weren’t enough, what time frame was plausible? The prognosis was grim in 1965 and frankly, half a century later, it’s still pretty bleak. If Malcolm, who was quite possibly the most honest, the most unselfish, the most badass MF to ever lift his voice in dissent, died ambivalent about American democracy, then what’s the best any of us can hope for?

*Bernard Aquina Doctor’s biography of Malcolm X is brief but powerful. His artwork and text convey the essence of this important, controversial icon in a manner that should appeal to a youthful demographic, as well as broken down old history buffs like me.

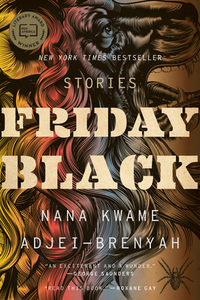

"...a jury of his peers had acquitted George Wilson Dunn of any wrongdoing whatsoever. He had been indicted for allegedly using a chain saw to hack off the heads of five black children outside the Finklestein Library in Valley Ridge, South Carolina. The court had ruled that because the children were basically loitering and not actually inside the library reading, as one might expect of productive members of society, it was reasonable that Dunn had felt threatened by these five black young people and, thus, he was well within his rights..."

Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah has a handle on dystopian fiction, whether it's political, societal, professional or even existential. This is a collection of twelve short stories that scale somewhere between transcendent hopefulness and soul-sucking despair. Not all of them will wow you, but most of them will viscerally impact you, and two or three of them will blow your freaking mind.

Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah has a handle on dystopian fiction, whether it's political, societal, professional or even existential. This is a collection of twelve short stories that scale somewhere between transcendent hopefulness and soul-sucking despair. Not all of them will wow you, but most of them will viscerally impact you, and two or three of them will blow your freaking mind.

“Nothing is so difficult as not deceiving yourself.” ~Ludwig Wittgenstein

As language, according to Wittgenstein, is wholly inadequate in the conveyance of thought, I have endeavored to put my review firmly in order by being silent about it.

As language, according to Wittgenstein, is wholly inadequate in the conveyance of thought, I have endeavored to put my review firmly in order by being silent about it.

O’Keeffe was the consummate “artist” and any characterization could easily have been stiff and stereotypical, but not here. Lisle, more often than not, was able to pry open that guarded, introverted, almost misanthropic oyster that was Georgia O’Keeffe and gift us all with a fleeting glimpse of the pearl inside.

As a biographer, Laurie Lisle can be informative, enlightening, and engaging—though almost never all at the same time. Her composition, as good as it is, left me with half as many questions as answers. The ending, for example, was strangely abrupt; it concluded with, almost literally, “…and then Georgia died. The End.” There was no introspection, no reflection, and very little room for remorse. I had the sense that this biographical endeavor had taken an exhausting toll on her and she was anxious to put it behind her. That’s all speculation on my part, of course, but there is no sense of closure here. ‘Portrait of an Artist’ ends where Georgia O’Keeffe ends—concluded but oddly unresolved.

Original review written August 3, 2022

________________________________________

Update: October 20, 2022

It turns out that this biography was originally published during Georgia O’Keeffe’s lifetime. An “updated edition” (reviewed above) was released after the artist passed away with add-on material that may or may not have been written by the author. This explains the oddly abrupt final chapter and why, in the interest of fairness, I have bumped up my rating to four stars.

As a biographer, Laurie Lisle can be informative, enlightening, and engaging—though almost never all at the same time. Her composition, as good as it is, left me with half as many questions as answers. The ending, for example, was strangely abrupt; it concluded with, almost literally, “…and then Georgia died. The End.” There was no introspection, no reflection, and very little room for remorse. I had the sense that this biographical endeavor had taken an exhausting toll on her and she was anxious to put it behind her. That’s all speculation on my part, of course, but there is no sense of closure here. ‘Portrait of an Artist’ ends where Georgia O’Keeffe ends—concluded but oddly unresolved.

Original review written August 3, 2022

________________________________________

Update: October 20, 2022

It turns out that this biography was originally published during Georgia O’Keeffe’s lifetime. An “updated edition” (reviewed above) was released after the artist passed away with add-on material that may or may not have been written by the author. This explains the oddly abrupt final chapter and why, in the interest of fairness, I have bumped up my rating to four stars.