Take a photo of a barcode or cover

mars2k's Reviews (234)

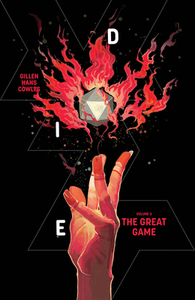

This book is strong in its own right too, tackling themes of war, death, and autonomy with tact and insightfulness. The central question of who is really in control weaves through the narrative and rears its head when

It’s rare that a piece of media that relies so heavily on breaking the fourth wall and being meta does so in a way that feels earned. All I can do now is hope that volume 4 gives Die the gratifying conclusion the series deserves.

Graphic: Cursing, Death, Violence, Grief, Murder, War

Moderate: Emotional abuse, Gore, Infertility, Terminal illness, Torture, Toxic relationship, Blood, Death of parent, Fire/Fire injury, Alcohol

Minor: Body horror, Child death, Confinement, Drug use, Gun violence, Homophobia, Rape, Sexual content, Suicide, Excrement, Suicide attempt

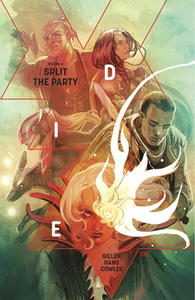

As I said at the beginning of this review, I do think Split the Party is a slight downgrade compared to Fantasy Heartbreaker. Die hasn’t dropped the ball but it is fumbling just a little. I hope this turns out to be the calm before the storm and that volume 3 takes the story to new heights. I’m excited to see where this goes.

Graphic: Cursing, Mental illness, Blood

Moderate: Adult/minor relationship, Confinement, Death, Emotional abuse, Infidelity, Sexual content, Violence, Grief, Fire/Fire injury

Minor: Alcoholism, Animal death, Biphobia, Gore, Misogyny, Sexism, Slavery, Terminal illness, Torture, Medical trauma, Death of parent, Murder, Pregnancy, Alcohol, Colonisation, War

I’m afraid there’s not much else to say. Why Art? is a nice little book. Definitely worth a read but don’t set your expectations unrealistically high. The drawings will make you smile, and the text will make you think. That’s all there is to it.

Minor: Cursing, Fire/Fire injury, Injury/Injury detail

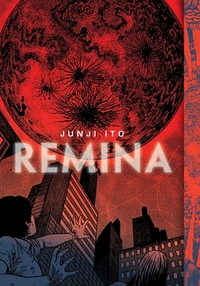

Also the ending didn’t make a whole lot of sense to me? Let’s just say I’d have written it very differently.

All in all, I kinda liked Remina. At the very least, I appreciate the effort. The artwork was great. The writing could have been better. It’s a shame the execution was a little lacking because Ito was working with some really interesting ideas. Three stars. Not quite three and a half.

Graphic: Body horror, Death, Misogyny, Torture, Violence, Kidnapping, Stalking, Death of parent, Murder

Moderate: Emotional abuse, Gore, Gun violence, Sexual assault, Blood, Grief, Fire/Fire injury

Minor: Cursing, Suicidal thoughts

I’m conflicted. I’m having a hard time identifying what’s actually significant and what’s just me projecting meaning onto something meaningless – which itself is both frustrating and fascinating. Is the prose supposed to be nonsensical? Are Negarestani and Parsani supposed to blur together into one voice? Am I supposed to examine the intentions of the author rather than suspending my disbelief and experiencing the fiction he has crafted? Am I massively overthinking this? I don’t know. Probably!

Graphic: Ableism, Body horror, Death, Gore, Mental illness, Racism, Self harm, Xenophobia, Schizophrenia/Psychosis , War, Injury/Injury detail

Moderate: Child death, Genocide, Gun violence, Misogyny, Rape, Sexual content, Blood, Islamophobia, Cannibalism, Murder

Minor: Alcoholism, Animal death, Chronic illness, Drug use, Eating disorder, Racial slurs, Suicidal thoughts, Suicide, Vomit, Alcohol

Graphic: Animal death, Child death, Death, Gun violence, Terminal illness, Grief

Moderate: Ableism, Alcoholism, Animal cruelty, Confinement, Sexism, Violence, Blood, Vomit, Police brutality, Medical content, Suicide attempt, Murder, Alcohol

Minor: Child abuse, Gore, Infidelity, Racism, Sexual content, Slavery, Mass/school shootings, Death of parent, Colonisation

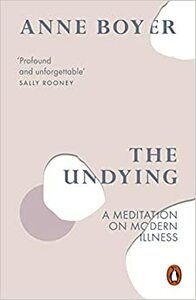

Graphic: Cancer, Chronic illness, Death, Terminal illness, Medical content, Grief

Moderate: Animal death, Drug use, Misogyny, Racism, Sexual content, Suicidal thoughts, Suicide, Torture, Blood, Vomit, Medical trauma, Death of parent

Minor: Ableism, Addiction, Bullying, Gore, Gun violence, Rape, Police brutality, Murder, Pregnancy, Alcohol

Graphic: Body horror, Child abuse, Child death, Death, Emotional abuse, Gore, Mental illness, Misogyny, Panic attacks/disorders, Self harm, Sexism, Suicide, Blood, Vomit, Medical content, Medical trauma, Murder, Schizophrenia/Psychosis , Injury/Injury detail

Moderate: Alcoholism, Animal death, Cancer, Chronic illness, Miscarriage, Suicidal thoughts, Violence, Grief, Pregnancy, Alcohol, War

Minor: Addiction, Adult/minor relationship, Bullying, Drug use, Eating disorder, Gun violence, Racism, Rape, Terminal illness, Torture, Xenophobia, Excrement, Antisemitism, Dementia, Cannibalism, Death of parent

Time Is the Thing a Body Moves Through is an interesting little book. I’ll probably revisit it at some point.

Graphic: Animal death, Death, Sexual content

Moderate: Drug use, Homophobia, Police brutality, Medical content, Alcohol

Minor: Adult/minor relationship, Animal cruelty, Deadnaming, Domestic abuse, Gun violence, Self harm, Sexual violence, Slavery, Suicide, Terminal illness, Torture, Transphobia, Violence, Blood, Vomit, Mass/school shootings, Murder, Colonisation, Dysphoria

What I will say is that this book serves as a nice sample platter of contemporary artists and philosophers. There are definitely some interviewees whose work I want to check out. But Violence: Humans in Dark Times itself doesn’t really deliver.

Graphic: Child death, Death, Genocide, Gun violence, Racial slurs, Racism, Suicide, Violence, Xenophobia, Police brutality, Mass/school shootings, Murder, War

Moderate: Ableism, Child abuse, Emotional abuse, Homophobia, Misogyny, Sexism, Sexual assault, Sexual content, Slavery, Torture, Transphobia, Antisemitism, Islamophobia, Kidnapping, Sexual harassment

Minor: Animal cruelty, Gore, Incest, Infidelity, Rape, Self harm, Blood, Medical content, Colonisation