Take a photo of a barcode or cover

toggle_fow's Reviews (1.05k)

Very interesting.

Gladwell's claim is that success is as much a measure of 1) luck and 2) social culture as it is of ability.

At first glance, a lot of this seemed to be the "they succeeded because of their attitude" kind of stereotype-based social science that called back to the "protestant work ethic" of Samuel Huntington. As the book went on, though, his examples and analysis were much more convincing than I expected them to be. It does make you feel kind of helpless, since the book is arguing that if you weren't born in the lucky right era or to the right family you're basically out of luck, but it is absolutely intriguing conceptually.

Gladwell's claim is that success is as much a measure of 1) luck and 2) social culture as it is of ability.

At first glance, a lot of this seemed to be the "they succeeded because of their attitude" kind of stereotype-based social science that called back to the "protestant work ethic" of Samuel Huntington. As the book went on, though, his examples and analysis were much more convincing than I expected them to be. It does make you feel kind of helpless, since the book is arguing that if you weren't born in the lucky right era or to the right family you're basically out of luck, but it is absolutely intriguing conceptually.

This book is founded on the dangerous false premise that "we are all God" and is decorated with a heavy, suffocating layer of mysticism. However, its practical advice for a healthy mental approach to life is actually pretty solid, if you can sift through all the woo-woo.

I read these books hoping that someday, someone will tell me something other than: "Yes, you have to do hard things." I don't WANT to do hard things. I want to sit in my pajamas in bed under my 6 weighted blankets eating ice cream and reading and writing stories for the rest of my life. That's ALL. Unfortunately, I have tried this, and it actually leads to depression rather than to happiness, so I had to throw out that approach to life.

As these types of books do, The Happiness Project leans on the author's life, personal reflections, and humor to provide upwards of eighty percent of its content. You learn an awful lot about Gretchen; sometimes I identified with her (the desire for legitimacy) and sometimes I cringed a little bit (her pushiness, and constant unkindness to her husband). Around the fluff, though, there is quite a bit of interesting information and some sadly valid insights about happiness.

A sample:

As these types of books do, The Happiness Project leans on the author's life, personal reflections, and humor to provide upwards of eighty percent of its content. You learn an awful lot about Gretchen; sometimes I identified with her (the desire for legitimacy) and sometimes I cringed a little bit (her pushiness, and constant unkindness to her husband). Around the fluff, though, there is quite a bit of interesting information and some sadly valid insights about happiness.

A sample:

• It takes 5 positive marital actions to repair the damage of 1 negative one

• Happiness comes from "an atmosphere of growth" -- from learning and overcoming and reaching for goals rather than from achieving goals (I HATE THIS but I know it's true??)

• Women test as having more empathy towards people than men do, but they both test as having the same amount of empathy towards animals

• Some things contribute massively to your overall happiness, but are unpleasant to do or experience

• Quite a bit of happiness is people-centered. Although maintaining relationships can be annoying and involve an awful amount of work, it pays big happiness dividends

Sheer malevolence motivated me to seek this book out.

I had heard so much about this book that I honestly couldn't take ONE more person wanting to rave to me about Jordan Peterson's 12 Rules for Life. My soul filled with pure, distilled hatred, I meant to get my hands on this book and systematically rip it apart line by line. In my resentment I just knew that the book HAD to be trash and I set out to prove it.

I still stand ready to kill anyone attempting to slobber their adoration for this book all over me. (It's fine if you like it! Just don't talk to ME about it.) Unfortunately, I can't exactly write the scorching, acidic review that I was hoping to write, either. The problem with this book is that it's massively bloated, rambly, and long-winded, not that its main premise is wrong.

The central idea of 12 Rules for Life is just that: Peterson puts forward 12 rules by which to live. He believes that these, if followed, will grant people meaningful, fulfilling lives. If you're expecting, like, psychology or brain science, there's hardly any of that here. This is more of a self-help book, along the lines of The Happiness Project, if it were written by an extreme intellectual who spends all day pondering philosophy.

The rules themselves are almost wholly unobjectionable, and you would hear them in one form or another from any source of worthwhile life improvement advice. Things like "assume the person you are listening to might know something you don't" and "compare yourself to who you were yesterday, not who someone else is today" and "make friends with people who want the best for you." Who could have a problem with things like that? Not me. The three stars I gave this book are for the two or three pages in every chapter where Peterson dishes out valuable and hard-hitting perspective shifts.

One of his foundational premises is that meaning instead of happiness should be the goal of life. Life involves suffering, he says. The way people seek happiness is to throw themselves into momentary feelgood experiences and flee from suffering, which only leads to a cycle of being increasingly more anxious and self-destructive. Meaning, which truly makes life bearable, comes from doing worthwhile things, pushing yourself, and growing. This is unfortunately true, even though I hate it.

Taking responsibility? "Volunteering" for life? Practicing gratitude instead of hiding behind protective nihilism? Disgusting. Ridiculous. I don't enjoy the fact that he's right, but I can't deny it.

Now, if he only spent two or three pages of chapter actually discussing that chapter's rule, what did he spend all the rest on? If you're wondering that, I can't tell you. I honestly don't know.

He talks... a lot.

Peterson likes archetypes and symbolism, so I will outline for you an archetypal 12 Rules for Life chapter:

Salt to taste and blend until smooth, and this list makes up the content of basically any given chapter in this book. Why is Genesis 1-4 necessary to cover in a chapter on "treat yourself like someone you are responsible for helping"? I may just not be subtil or sophisticated enough to understand the complex philosophy going on in these thirty-page chapters, but I cannot escape the conclusion that Peterson could have written 70% less and had a better book. I hope you can see what I mean.

The genuinely problematic things are sprinkled in sparingly:

• Peterson's ideology is that through hard work and good character you can morally redeem humanity and make the world into Paradise, so, while he likes Christianity a lot, he criticizes it for its ideas that salvation cannot be achieved through works, and Paradise is reserved for the afterlife; thus, he misses the entire point of Christianity and distorts all the scripture he won't stop harping on.

• Lots and lots of talk about gender. While I don't disagree with all of his thoughts, I do disagree with some, and I honestly don't know why he included any of them in the book. Peterson is VERY in love with manly toughness, and not being a sensitive pansy with feelings. Almost every mention of women is in the context of their all-important role as wife/mother/choosy sexual partner who bestows access to her reproductive system only to the most dominant of the hordes of slavishly begging men. (Peterson is not an incel, but boy you can see why the incels would listen to him.)

• One chapter about taking responsibility instead of blaming others tries to exhort you to fix your own failings because they're the only things under your control, but the hypothetical stories he tells verge on victim blaming.

• He says that boys don't compete with girls because they "can't win." A girl can win honor by winning against a girl, and double honor winning against a boy, but a boy can win honor only by winning against boys. This may be true in the example he uses: a physical fistfight. How is this true, though, when a girl and a boy play wall ball on the playground? He says this to explain, apparently, the reasons why it is natural and normal that girls are socially allowed to cross over into "boy" things, but boys aren't allowed the reverse.

All of these tangents pop up like raisins in an otherwise delicious cookie. Most of them make you wonder why we are even talking about them. To me, the biggest sin of the book is not the sometimes weird, suspect, or cringey things that are sometimes included. Instead, it's the fact that they were included at all, when 99% of them are ABSOLUTELY IRRELEVANT.

I'm not even joking, Peterson goes over the first several chapters of Genesis in detail like five times. And I still DON'T EVEN KNOW WHY. I have no problem with Genesis, but it's so repetitive. He hammers you with The Gulag Archipelago in almost every chapter too, and his constant talk about Stalin and Hitler feels canned after the first several chapters. It's almost like he meant every chapter to be read as a separate essay, because then it wouldn't seem like he's repeating himself over and over and has nothing new to say.

The good advice is there, mostly straightforward. Then he veers and starts hitting you with "the snake in the Garden of Eden is a metaphor for the element of chaos present even in the most perfect place," and "Eve shames Adam the same way women spurn men and make them resentful even today." His symbolic interpretations seem based on nothing and are hard to believe in -- and he does this with everything, even Disney movies. All this, and we still don't even know why he brought up Adam and Eve in almost every chapter in the first place.

There is so much empty philosophy and unsubstantiated social theory crammed in every corner of every chapter, and it was extremely difficult for me to follow how all of it was connected to the actual life advice. This is the biggest issue with this book. It's distended far past the healthy structure it should have had. It's collapsing under its own weight.

Peterson needed a middle school writing teacher to put big red question marks by paragraphs and write "HOW DOES THIS SUPPORT THE THESIS?" Really, it's no surprise that his hobby is writing answers on Quora, that hallowed ground of the IQ obsessive. The list of 12 rules might have made it to print, but the rest of this book should have stayed on Quora.

I had heard so much about this book that I honestly couldn't take ONE more person wanting to rave to me about Jordan Peterson's 12 Rules for Life. My soul filled with pure, distilled hatred, I meant to get my hands on this book and systematically rip it apart line by line. In my resentment I just knew that the book HAD to be trash and I set out to prove it.

I still stand ready to kill anyone attempting to slobber their adoration for this book all over me. (It's fine if you like it! Just don't talk to ME about it.) Unfortunately, I can't exactly write the scorching, acidic review that I was hoping to write, either. The problem with this book is that it's massively bloated, rambly, and long-winded, not that its main premise is wrong.

The central idea of 12 Rules for Life is just that: Peterson puts forward 12 rules by which to live. He believes that these, if followed, will grant people meaningful, fulfilling lives. If you're expecting, like, psychology or brain science, there's hardly any of that here. This is more of a self-help book, along the lines of The Happiness Project, if it were written by an extreme intellectual who spends all day pondering philosophy.

The rules themselves are almost wholly unobjectionable, and you would hear them in one form or another from any source of worthwhile life improvement advice. Things like "assume the person you are listening to might know something you don't" and "compare yourself to who you were yesterday, not who someone else is today" and "make friends with people who want the best for you." Who could have a problem with things like that? Not me. The three stars I gave this book are for the two or three pages in every chapter where Peterson dishes out valuable and hard-hitting perspective shifts.

One of his foundational premises is that meaning instead of happiness should be the goal of life. Life involves suffering, he says. The way people seek happiness is to throw themselves into momentary feelgood experiences and flee from suffering, which only leads to a cycle of being increasingly more anxious and self-destructive. Meaning, which truly makes life bearable, comes from doing worthwhile things, pushing yourself, and growing. This is unfortunately true, even though I hate it.

Taking responsibility? "Volunteering" for life? Practicing gratitude instead of hiding behind protective nihilism? Disgusting. Ridiculous. I don't enjoy the fact that he's right, but I can't deny it.

Now, if he only spent two or three pages of chapter actually discussing that chapter's rule, what did he spend all the rest on? If you're wondering that, I can't tell you. I honestly don't know.

He talks... a lot.

Peterson likes archetypes and symbolism, so I will outline for you an archetypal 12 Rules for Life chapter:

1. Amusing or personal anecdote introducing the rule.

2. General explanation of the rule

3. Something about Freud or Jung (or both) and the primordial depths of the human psyche

4. Men and women are very different and here is how and why (it's about breeding and reproduction)

5. Genesis 1-4

6. Sociobiological theorizing linking modern people's behavior to the life of a long-ago genetic ancestor (IT'S ABOUT BREEDING AND REPRODUCTION)

7. Communism, fascism, and a book called The Gulag Archipelago

8. DOMINANCE HIERARCHY

9. One or two pages re-summarizing the rule but not really tying it back to anything else

Salt to taste and blend until smooth, and this list makes up the content of basically any given chapter in this book. Why is Genesis 1-4 necessary to cover in a chapter on "treat yourself like someone you are responsible for helping"? I may just not be subtil or sophisticated enough to understand the complex philosophy going on in these thirty-page chapters, but I cannot escape the conclusion that Peterson could have written 70% less and had a better book. I hope you can see what I mean.

The genuinely problematic things are sprinkled in sparingly:

• Peterson's ideology is that through hard work and good character you can morally redeem humanity and make the world into Paradise, so, while he likes Christianity a lot, he criticizes it for its ideas that salvation cannot be achieved through works, and Paradise is reserved for the afterlife; thus, he misses the entire point of Christianity and distorts all the scripture he won't stop harping on.

• Lots and lots of talk about gender. While I don't disagree with all of his thoughts, I do disagree with some, and I honestly don't know why he included any of them in the book. Peterson is VERY in love with manly toughness, and not being a sensitive pansy with feelings. Almost every mention of women is in the context of their all-important role as wife/mother/choosy sexual partner who bestows access to her reproductive system only to the most dominant of the hordes of slavishly begging men. (Peterson is not an incel, but boy you can see why the incels would listen to him.)

• One chapter about taking responsibility instead of blaming others tries to exhort you to fix your own failings because they're the only things under your control, but the hypothetical stories he tells verge on victim blaming.

• He says that boys don't compete with girls because they "can't win." A girl can win honor by winning against a girl, and double honor winning against a boy, but a boy can win honor only by winning against boys. This may be true in the example he uses: a physical fistfight. How is this true, though, when a girl and a boy play wall ball on the playground? He says this to explain, apparently, the reasons why it is natural and normal that girls are socially allowed to cross over into "boy" things, but boys aren't allowed the reverse.

All of these tangents pop up like raisins in an otherwise delicious cookie. Most of them make you wonder why we are even talking about them. To me, the biggest sin of the book is not the sometimes weird, suspect, or cringey things that are sometimes included. Instead, it's the fact that they were included at all, when 99% of them are ABSOLUTELY IRRELEVANT.

I'm not even joking, Peterson goes over the first several chapters of Genesis in detail like five times. And I still DON'T EVEN KNOW WHY. I have no problem with Genesis, but it's so repetitive. He hammers you with The Gulag Archipelago in almost every chapter too, and his constant talk about Stalin and Hitler feels canned after the first several chapters. It's almost like he meant every chapter to be read as a separate essay, because then it wouldn't seem like he's repeating himself over and over and has nothing new to say.

The good advice is there, mostly straightforward. Then he veers and starts hitting you with "the snake in the Garden of Eden is a metaphor for the element of chaos present even in the most perfect place," and "Eve shames Adam the same way women spurn men and make them resentful even today." His symbolic interpretations seem based on nothing and are hard to believe in -- and he does this with everything, even Disney movies. All this, and we still don't even know why he brought up Adam and Eve in almost every chapter in the first place.

There is so much empty philosophy and unsubstantiated social theory crammed in every corner of every chapter, and it was extremely difficult for me to follow how all of it was connected to the actual life advice. This is the biggest issue with this book. It's distended far past the healthy structure it should have had. It's collapsing under its own weight.

Peterson needed a middle school writing teacher to put big red question marks by paragraphs and write "HOW DOES THIS SUPPORT THE THESIS?" Really, it's no surprise that his hobby is writing answers on Quora, that hallowed ground of the IQ obsessive. The list of 12 rules might have made it to print, but the rest of this book should have stayed on Quora.

Me reading this book: I will DIE if I don't get to walk across Afghanistan this VERY second.

Me, remembering I'm a girl: Actually... maybe that's reversed.

Me, remembering I'm a girl: Actually... maybe that's reversed.

This book isn't amazing.

It attempts to be a postmortem of the decision-making of the Vietnam War. It succeeds at being a sort of general portrait of three men circling the edges of the war. Despite the title, it spends just as much time on Johnson and Kennedy as it does on Bundy himself.

This book ostensibly distills its thesis into "lessons" learned from Bundy's experience, but the lessons range from painfully obvious to so abstract and general that they're practically useless. They mostly get lost in the meat of the chapter, just parroted once at the beginning and once at the end to give the illusion of structure. Overall, it works as a rough sketch of the dynamics contributing to the war, and an introduction to the major players and events.

McGeorge Bundy, a genius: Look, losing the war is fine, as long as we sacrifice 100,00 lives first.

It attempts to be a postmortem of the decision-making of the Vietnam War. It succeeds at being a sort of general portrait of three men circling the edges of the war. Despite the title, it spends just as much time on Johnson and Kennedy as it does on Bundy himself.

This book ostensibly distills its thesis into "lessons" learned from Bundy's experience, but the lessons range from painfully obvious to so abstract and general that they're practically useless. They mostly get lost in the meat of the chapter, just parroted once at the beginning and once at the end to give the illusion of structure. Overall, it works as a rough sketch of the dynamics contributing to the war, and an introduction to the major players and events.

McGeorge Bundy, a genius: Look, losing the war is fine, as long as we sacrifice 100,00 lives first.

Certainly, the one thing we can say absolutely is that I am not educated enough to accurately review this book.

I am still not sure I understand what parts of this book were saying. Other parts made me recoil with revulsion and I'm still not sure what they meant. Other parts made me think hard.

This book is a... poetic essay on colonialism and how the colonial relationship psychologically impacts colonized peoples. It's translated from French, so that might influence why the language is ethereal and sometimes difficult to grasp. I'm not at all sure of the provenance of the psychological concepts, or whether things like dream analysis and Freudian sexuality hold up scientifically today.

I do know that this book took me completely out of my body and dunked me headfirst into concepts that I had never examined before. Here is an Aime Cesaire quote the author includes that should give you a glimpse:

I am still not sure I understand what parts of this book were saying. Other parts made me recoil with revulsion and I'm still not sure what they meant. Other parts made me think hard.

This book is a... poetic essay on colonialism and how the colonial relationship psychologically impacts colonized peoples. It's translated from French, so that might influence why the language is ethereal and sometimes difficult to grasp. I'm not at all sure of the provenance of the psychological concepts, or whether things like dream analysis and Freudian sexuality hold up scientifically today.

I do know that this book took me completely out of my body and dunked me headfirst into concepts that I had never examined before. Here is an Aime Cesaire quote the author includes that should give you a glimpse:

People are surprised, they become indignant. They say: "How strange! But never mind--it's Nazism, it will pass!" And they wait, and they hope; and they hide the truth from themselves, that it is barbarism, the supreme barbarism, the crowning barbarism that sums up all the daily barbarisms; that it is Nazism, yes, but that before they were its victims, they were its accomplices; that they tolerated that Nazism before it was inflicted on them, that they absolved it, shut their eyes to it, legitimized it, because, until then, it had been applied only to non-European peoples; that they have cultivated that Nazism, that they are responsible for it, and that before engulfing the whole edifice of Western, Christian civilization in its reddened waters, it oozes, seeps and trickles from every crack.

Like if you're reading this in 1962 because JFK made you.

I'm on a WWI kick right now and it is fascinating. This book just deals with the political and military lead-up to the war, and the first month of the conflict. It is pretty dense and took me about two weeks to get through, when I can do a fantasy book of similar size in three or four hours. There were parts where I almost lost interest, but also parts that are hilarious. Overall, this is a great window into one of the most significant, yet least-understood events the world has ever seen.

I'm on a WWI kick right now and it is fascinating. This book just deals with the political and military lead-up to the war, and the first month of the conflict. It is pretty dense and took me about two weeks to get through, when I can do a fantasy book of similar size in three or four hours. There were parts where I almost lost interest, but also parts that are hilarious. Overall, this is a great window into one of the most significant, yet least-understood events the world has ever seen.

I genuinely enjoy this book a lot. However, it is half delightful, half just plain gross.

The delight comes from the odd combination of Feynman's genuine intellect and his inability to operate at any level other than maximum zaniness at all times. Half of the "big fish stories" he tells, for which he is famous, are nearly unintelligible because he insists on explaining the "simple" math he used to trick some of his peers. Like yeah, okay, I could probably understand this given a 15-minute-long detailed breakdown, but I'm not just going to suddenly get the joke with 2 paragraphs of explanation on logarithms.

Somehow, the stories are always still entertaining.

Any sentence that begins "when I was a kid" is the worst, because it's invariably going to end with something horrible like "I built radios from scratch" or "differentiating under the integral sign was my favorite trick." It could really give you some kind of a complex. Are kids these days just dullards? Am I the only dullard, because I spent my childhood making pretend soup out of grass and playing Lego Star Wars?

I really get the impression that Feynman would either be hilarious or intolerable to know personally, and possibly it might depend on the day. Almost all of his stories about studying at MIT, teaching at Cornell, and working in Los Alamos on the Manhattan Project are basically just stories of the chicanery and mischief he was able to cause for his peers and colleagues. The whole atom bomb part is like an afterthought to accounts of the minor trouble he was able to make picking locks that oughtn't to be picked and playing unnecessary games with the censors in his outgoing letters.

He's clearly a MASSIVE showoff and a compulsive provocateur. Truly a mad lad.

A representative quote:

I first read this book when I was a teenager, and mostly remembered the amusing anecdotes. Unfortunately, on a second reading, the gross jumps out a lot more. Feynman is a womanizer, and he seems to be proud of or at least unapologetic about it.

Several of his pranks come off as thoughtlessly selfish, almost cruel, and the way he conducts himself in personal relationships just emphasizes that. It seems as though he probably cheated on every wife he ever had (at least three of them) and there are far, far too many stories of his pickups and escapades. The girl-chasing motivations are clear from the beginning of the book, but it really gets worse as he gets older. At least when he was young he was doing a lot of science, but the chapters about his later years feature ridiculously unnecessary details about his forays into amateur artistry (nude models), recreation (Vegas showgirls, topless clubs), and investigations into sensory deprivation (nudist resorts).

Yuck, yuck, yuck. Even when you're calling women "nifty-looking," it doesn't dull the repulsiveness of a fifty-something-year-old man evaluating the sex appeal of every young female to cross his path. I honestly love this book, but I wish I could admire Feynman fully, instead of having this huge, ugly caveat thrust under my nose so often.

The delight comes from the odd combination of Feynman's genuine intellect and his inability to operate at any level other than maximum zaniness at all times. Half of the "big fish stories" he tells, for which he is famous, are nearly unintelligible because he insists on explaining the "simple" math he used to trick some of his peers. Like yeah, okay, I could probably understand this given a 15-minute-long detailed breakdown, but I'm not just going to suddenly get the joke with 2 paragraphs of explanation on logarithms.

Somehow, the stories are always still entertaining.

Any sentence that begins "when I was a kid" is the worst, because it's invariably going to end with something horrible like "I built radios from scratch" or "differentiating under the integral sign was my favorite trick." It could really give you some kind of a complex. Are kids these days just dullards? Am I the only dullard, because I spent my childhood making pretend soup out of grass and playing Lego Star Wars?

I really get the impression that Feynman would either be hilarious or intolerable to know personally, and possibly it might depend on the day. Almost all of his stories about studying at MIT, teaching at Cornell, and working in Los Alamos on the Manhattan Project are basically just stories of the chicanery and mischief he was able to cause for his peers and colleagues. The whole atom bomb part is like an afterthought to accounts of the minor trouble he was able to make picking locks that oughtn't to be picked and playing unnecessary games with the censors in his outgoing letters.

He's clearly a MASSIVE showoff and a compulsive provocateur. Truly a mad lad.

A representative quote:

"I listened to all this, and I was happy." — Feynman after framing others for mischief they didn't commit and causing an uproar and near-brawl among the members of his fraternity

I first read this book when I was a teenager, and mostly remembered the amusing anecdotes. Unfortunately, on a second reading, the gross jumps out a lot more. Feynman is a womanizer, and he seems to be proud of or at least unapologetic about it.

Several of his pranks come off as thoughtlessly selfish, almost cruel, and the way he conducts himself in personal relationships just emphasizes that. It seems as though he probably cheated on every wife he ever had (at least three of them) and there are far, far too many stories of his pickups and escapades. The girl-chasing motivations are clear from the beginning of the book, but it really gets worse as he gets older. At least when he was young he was doing a lot of science, but the chapters about his later years feature ridiculously unnecessary details about his forays into amateur artistry (nude models), recreation (Vegas showgirls, topless clubs), and investigations into sensory deprivation (nudist resorts).

Yuck, yuck, yuck. Even when you're calling women "nifty-looking," it doesn't dull the repulsiveness of a fifty-something-year-old man evaluating the sex appeal of every young female to cross his path. I honestly love this book, but I wish I could admire Feynman fully, instead of having this huge, ugly caveat thrust under my nose so often.

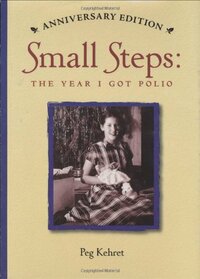

This is a memoir of a 12-year-old girl who contracted polio, her experience with the disease itself and the recuperation afterward, and it's VERY fascinating.

First of all, this is yet another book I found while shelving the children's section when I worked at Barnes & Noble. It's written in a clear, simple, diary style that I imagine young grade schoolers would understand without difficulty, but that also perfectly conveys the fear and pain of the author's experiences. It's a very fast and easy read, and packed with all sorts of things that seem revelatory and alien-strange to a person like me, born and raised in a post-polio world.

First of all, this is yet another book I found while shelving the children's section when I worked at Barnes & Noble. It's written in a clear, simple, diary style that I imagine young grade schoolers would understand without difficulty, but that also perfectly conveys the fear and pain of the author's experiences. It's a very fast and easy read, and packed with all sorts of things that seem revelatory and alien-strange to a person like me, born and raised in a post-polio world.