Take a photo of a barcode or cover

Mən əvvəlcə son kitabı, sonra ilk kitabı oxuyan biri olaraq onu deyim ki, bu son kitabı bəyəndim. Işarələdiyim yerlər çox oldu. Ilk kitabı alıb peşman oldum sonra. Ona görə də tək bu kitabl oxumaq belə bəs edə bilər. Düzü, ortadakı kitabları oxumamışam və kitabları ingiliscə oxumuşam. Bəlkə türkcə oxusaydım, ilk kitabı da bəyənər və davam kitablarını da alardım. Amma belə alındı ki, ilk kitaba heç cür isinişə bilmədim.

challenging

informative

reflective

medium-paced

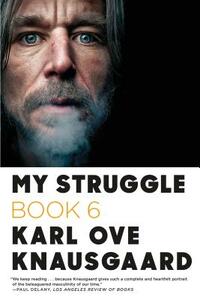

This is fitting end this massive series. 1000 pages of real time descriptions of the mundane with phylosophical discourse. This time with a several hundred page discourse comparing Hitler - his struggle his use of langue with his own. Overlong but still masterful.

Karl Ove Knausgaard has been a constant companion since I started the first volume, back in 2018. And now, here in the midst of uncertain 2020, having started this book at the beginning of lockdown, I've finally reached the end of volume 6. And I'm sad to see him go.

To begin with, the first part of the book concerns the reaction of his family, in particular that of his uncle, to the previous volumes. It then moves into a 400 page discussion of Hitler, in particular his time in Vienna, before he looks at the writing of Mein Kampf (with title of min kamp, this wasn't a surprising diversion) before ending with a touching and emotional description of his wife experiencing a severe depressive episode. In between there are lots of trips to the kindergarten with the children, lots of coffee drank and cigarettes smoked on the balcony.

After I've finished a volume, I'm never sure what I've just read, and how i feel about it. And this is no different. I did find the Hitler diversion a bit of a trial at times, and I'm not 100% sure about the point of it. But for the rest of the time, I found his writing style riveting, in how he can make the mundane so fascinating, and how he can be so honest with how he feels about his life and those around him.

There's a fair amount of detail about what he was hoping to acheive with these volumes, a sense that he had to be free to write these things, and had to be inconsiderate to others to do so. He acknowledges that he has hurt those closest to him, and it will be painful for his children to read in later years. At one stage he describes the enterprise as 'two sons who bury their dead father and a frustrated father of small children who strips himself naked for the reader' but it's much more than that. Sometimes frustrating, always engrossing, I've never read anything quite like this.

To begin with, the first part of the book concerns the reaction of his family, in particular that of his uncle, to the previous volumes. It then moves into a 400 page discussion of Hitler, in particular his time in Vienna, before he looks at the writing of Mein Kampf (with title of min kamp, this wasn't a surprising diversion) before ending with a touching and emotional description of his wife experiencing a severe depressive episode. In between there are lots of trips to the kindergarten with the children, lots of coffee drank and cigarettes smoked on the balcony.

After I've finished a volume, I'm never sure what I've just read, and how i feel about it. And this is no different. I did find the Hitler diversion a bit of a trial at times, and I'm not 100% sure about the point of it. But for the rest of the time, I found his writing style riveting, in how he can make the mundane so fascinating, and how he can be so honest with how he feels about his life and those around him.

There's a fair amount of detail about what he was hoping to acheive with these volumes, a sense that he had to be free to write these things, and had to be inconsiderate to others to do so. He acknowledges that he has hurt those closest to him, and it will be painful for his children to read in later years. At one stage he describes the enterprise as 'two sons who bury their dead father and a frustrated father of small children who strips himself naked for the reader' but it's much more than that. Sometimes frustrating, always engrossing, I've never read anything quite like this.

Knausgaard finishes the series with a book that focuses on reality and fiction, on the public realm, our private lives, the I and the We. It's fascinating. I got the feeling of “goodbye” throughout the entire book. He begins talking about the consequences of his writing -now that the first books of the series are getting published- specially about those involving his family. The anger of his uncle and his own fear towards the reactions of them who he'd written about. He then begins a deep and obsessive analysis to one of Paul Celan's poems where every word is scrutinized. Then 400 pages on Hitler. Then his relationship with Linda. And more about his life. Normal life, daily tasks, being a parent, drinking coffee and smoking a cigarette on the balcony. He still suffers, but is a pain that's understood, and as a reader you get it. This didn’t happen in the first books.

The banality of ordinary life can be painful seen with cloudy eyes and the wrong mind set. But it is beautiful once you accept it. I treasure every page, sure I do. The closing pages are heart breaking, but it is life all the while. His incredible prose never ceases to amaze. Lots of literature and children talk. Religion, meaning, our perceptions, Ulysses, Hamlet, the Bible. This book is a beautiful and a challenging closure.

The banality of ordinary life can be painful seen with cloudy eyes and the wrong mind set. But it is beautiful once you accept it. I treasure every page, sure I do. The closing pages are heart breaking, but it is life all the while. His incredible prose never ceases to amaze. Lots of literature and children talk. Religion, meaning, our perceptions, Ulysses, Hamlet, the Bible. This book is a beautiful and a challenging closure.

challenging

dark

emotional

reflective

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Complicated

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Diverse cast of characters:

No

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

challenging

emotional

funny

informative

inspiring

reflective

fast-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Complicated

Loveable characters:

Yes

Diverse cast of characters:

No

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

I loved it. Even the Hitler section, it all hung together for me. In fact at some point that became some of the most absorbing reading, once I got past the Paul Celan poem analysis and a few hundred pages into the Hitler bio, it really gripped me and I just flew along. Really the last five hundred pages or so, I practically tore through.

The Celan poem stuff was slow going. If this had been the first book, I would've given up there. It felt like, a hundred pages of close reading this poem? And then we have four hundred pages of Hitler? Before we get back to the good stuff? But it wasn't the first book; I trusted his project; so I read the Celan stuff, and the Hitler stuff, which was a relief after Celan, and then of course the last three hundred pages, which to me were about why he needed to go so deep into the Hitler/Celan stuff.

I think the project is to be present, to see things as they are and by publicly describing them that way, to show readers the importance of being present in our own life. Not by his example, his being the sacrifice, or the lesson-in-learning. But the long section on Hitler, the you, the we, the it, the I of Celan’s poem, these are also about Linda, about seeing her, being with her, and never prioritizing the importance of any work over the importance of a person. The ending is the aftermath—but it contains its own ending, a "this is why it has to end."

The Celan poem stuff was slow going. If this had been the first book, I would've given up there. It felt like, a hundred pages of close reading this poem? And then we have four hundred pages of Hitler? Before we get back to the good stuff? But it wasn't the first book; I trusted his project; so I read the Celan stuff, and the Hitler stuff, which was a relief after Celan, and then of course the last three hundred pages, which to me were about why he needed to go so deep into the Hitler/Celan stuff.

I think the project is to be present, to see things as they are and by publicly describing them that way, to show readers the importance of being present in our own life. Not by his example, his being the sacrifice, or the lesson-in-learning. But the long section on Hitler, the you, the we, the it, the I of Celan’s poem, these are also about Linda, about seeing her, being with her, and never prioritizing the importance of any work over the importance of a person. The ending is the aftermath—but it contains its own ending, a "this is why it has to end."

My question is why we conceal the things we do.

That's the project.

And what I related to then only instinctively or emotionally, the social world, whose power I felt whenever my cheeks burned with shame or I was consumed by self-reproach because of something I had done that made me feel so inadequate, so awkward, so indistinct, so totally stupid and foolish, but also unprincipled and dishonest and fraudulent, I now see more clearly, not least after having written these books, which in their every sentence have tried to transcend the social world by conveying the innermost thoughts and innermost feelings of my most private self, my own internal life, but also by describing the private sphere of my family as it exists behind the façade all families set up against the social world, doing so in a public form, a novel.

Meditating on the coming death of Magne, terminally ill, at a get-together with that family in the fjords at Dale in lyrical weather:

... Magne, whom I had known all my life, was terminally ill. He had always been a strong and vigorous man, a focal point in any gathering, a man of immense charisma, impossible to ignore. Sitting there now he was hardly recognizable. Physically he wasn’t much changed, but his presence had gone. He was hardly there, and it pained me the whole time, even when he was out of sight, I couldn’t grasp it, that such a total transformation could be possible, I’d always equated his presence with him, the person he was, to me they were the same. Now he was a shadow of himself. He chatted a bit, ate a little, occasionally gazing out over the fjord, surrounded by his children and grandchildren, on what was perhaps the most beautiful day of that whole summer. | Everything he saw would soon be gone to him, and would never come back. | Not just his family, whose fates and destinies he would never know, but also the fjord and the fells, the grass and the humming insects. And the sun. He would never see the sun again. | These thoughts tainted everything I saw that day. The beauty of the world became enhanced, and yet it seemed crueler too, for one day it would be gone to me too, and continue to exist for those who remained, as it had done since the beginning of time. How many people had sat where we were sitting and looked at the same view? Generation after generation stretching back in time, all here once, all gone now. | When evening came and it was time to go home, Vanja wanted to go with Heidi and Linda, so I drove with John, who slept, an hour and a half beneath the towering fells, through the valleys where the shadows of approaching night grew long, past the racing rivers and gushing waterfalls, and all the time I sang out loud, drunk on the sun and death. | What else could I do? I was so happy.

I was surprised sometimes by the text having a bit of obvious style—in the past books, as I recall, he almost never let himself have any literary style, he just wrote (it seemed) what he was thinking, first-draft, erring on the side of the banal. I do wonder how much editing still goes into that apparently unpolished style. But occasionally in this book, more than in the others, I noticed "nice bits":

...while the loss of the self in reading is to the alien I, which, by virtue of being so obviously apart from the reader’s own singular I, does not seriously threaten its integrity, the loss of the self in writing is in a different way complete, as when snow vanishes into snow (my emphasis)

or

But there was nothing to be afraid of, was there? The plane was no more than a tiny dot now while daybreak seemed to have come closer to the town, and the darkness in the air between the buildings below me was filled with a kind of light so hazy that it was as if someone had stirred the gloom, causing the light hiding at the bottom to mingle and rise to the surface.

As opposed to his usual style (which I also like):

The worms and snails that slither as best they can

I love his outbursts:

Oh, how then, for crying out loud, can we make the lives we live an expression of life, rather than the expression of an ideology?

Why do I organize my life like this? What do I want with this neutrality? Obviously it is to eliminate as much resistance as possible, to make the days slip past as easily and unobtrusively as possible. But why? Isn’t that synonymous with wanting to live as little as possible? With telling life to leave me in peace so that I can… Yes, well, work? Read? Oh, but come on, what do I read about, if not life? Write? Same thing. I read and write about life. The only thing I don’t want life for is to live it.

His insights about the social world:

“The law regulates violence among like kind”

The whole of this enormous world, teeming with detail, was divided into intricate, finely meshed systems that kept everything apart, at first by its very division into sectors, which meant that rubber tap washers, for instance, were to be found in a different place than nylon guitar strings, and a novel by Danielle Steel in a different place than a novel by Daniel Sjölin, which was a kind of rough, initial sorting, then by infusing the various goods or services with value, thereby grading them in ways no school could ever teach, and which therefore had to be learned ad hoc, outside any school or institution, and which furthermore were forever in a state of flux. This was the difference between a pair of McGordon jeans from Dressmann and a pair of Acne jeans, or a pair of Tommy Hilfiger jeans and a pair of Cheap Monday jeans, Ben Sherman or Levi’s, Lee or J. Lindeberg, Tiger or Boss, Sand or Peak Performance, Pour or Fcuk. … I knew perfectly well what kind of sofa sent out what kind of signals, and the same was true of electric kettles and toasters, running shoes and schoolbags. Even tents were something I would be able to appraise, at least to a certain extent, in terms of what kind of signals they sent out. This knowledge was not written down anywhere, and it was hardly accepted as knowledge at all, it was more an assurance regarding the way things stood, and it fluctuated according to the social strata in such a way that someone from the upper classes would be able to frown on my sofa preferences and the sofa knowledge I was thereby demonstrating, just as I in turn would be able to frown on the taste in sofas of people belonging to a lower status group than myself, not in any way denigrating them as human beings, because I wouldn’t dream of doing such a thing, but their sofas. I might not say so out loud, for fear of seeming judgmental, but I would think, God, what an awful sofa. Such knowledge, which applied to nearly all brands and their practical and social significance, was immense, and, I occasionally thought to myself, not that different from the knowledge so-called primitive peoples once possessed, where they not only knew the name of every plant, tree, and bush in their surroundings but also what kind of properties they had and what use could be made of them…. This knowledge wasn’t something they considered, nor was it ever made a show of in any way, since basically they were unaware of its existence as such, so closely was it bound up with their own being. Such is the case too with the immense knowledge we ourselves possess, of the difference between strong and mild mustard, for instance…. Like the people who went before us, we don’t give a thought to the knowledge required for us to get through the day, we don’t see it, it’s a part of us, it’s who we are. Our world is this: Blaupunkt over bluebell, Rammstein over rowan, Fiat over foxglove.

His introspection into everything:

That live prawns were pale and sleet-colored, bordering on the transparent, much like dirty windows, hardly seemed credible when you saw them cooked, the color being such a strong and splendid characteristic you could hardly imagine that nature should squander it on something dead. The lobster, on the other hand, in it’s somber, steely armor not unlike certain suits of armor in the Italian Renaissance, black and articulated, certainly finer living than when the boiling water so swiftly extinguished its life and the red-orange color seeped into the shell. To be sure it was a delicate thing to behold. More elegant, but compared to the beauty of the black and all its associations with power and strength, the refinement of red was nothing. How different in the case of the prawns. Alive they looked almost like office workers of the ocean, in death like a company of ballet dancers. | Below us a bus stopped with a sigh at a red light.

I think the above passage is so great because it follows some lengthy introspection about death, the social world, comedy and tragedy, Dostoevsky’s The Idiot; and then he regrounds us in his moment, up on the balcony with Geir, in the hot evening sun, are we meant to believe that’s what they have been talking about? Given that so much of his ideas, he says, are from Geir? And the same speculation, the same critical analysis, applied to the aesthetics of the prawns on the table as the grand concepts of life and death, as if he’s unable to stop wondering and questioning and thinking, reflecting.

Best of all though, I just like the moments of everyday life—the lyrical, the banal, the plain description of everything.

I stayed in the living room and watched her go past with the lantern glowing in her hand in the dim light. Then I carried the ice cream out, and the fruit, the wafers, and the coffee, all on a tray, together with the cups, plates, and spoons. | The darkness in August is the finest darkness of all. It lacks the luminous transparency of June’s, the sheer ripeness of its potentialities, yet is quite unlike the impenetrable depths of autumn’s or winter’s darkness. What was with us before and now is gone, spring and summer, lingers on in August darkness, whereas what is to come, autumn and winter, are a time into which we can only peer, a time of which we are not yet a part. | ... | ... Life is there for the living. Through autumn and winter, spring and summer, fuller with every turn. Wasn’t that what was happening? Never had the darkness of August felt more replete than now.| Replete with what? | The beauty of time passing.

There were parts in the Hitler section I remembered from The Great War and Modern Memory—so many people so excited for World War I breaking out. All the young men worried they would miss it. But other new aspects: for example, how fashionable young man at the time in their mid-twenties would grow impressive beards and acquire paunches and wear glasses even if their vision was perfect, wanting to be middle-aged. And as far as Hitler's participation in the war, his first engagement in the fighting as a part of the List Regiment, immediately after basic training—his regiment numbered 3,600 men when they got to Ypres on October 23, so excited on the train ride down at the thought of fighting. And then, after those first four days of action, only 611 were left.

Lyrical philosophizing around page 624. Eventually, echoing the beginning of the first book: "As indeed is the heart, for like death the heart is always the same. The heart is not modern either. It is neither reasonable nor unreasonable, neither rational nor irrational. The heart beats, and then it does not. That’s it."

Great example of the technique I love in which emotional distress is revealed late, almost indirectly, not directly in the moment (which is often how it happens really):

"See you later then," I said. | "Yes, see you," she said, and turned to two other patients standing there as I set off. At home I took my bike out of the cellar, it was a DBS I’d chosen from a selection of probably better bikes, only because the name reminded me of my childhood, the spring light, the smell of the sea between the spruce trees. I cycled to Flüggers Färg on Köbenhavnervagen and bought some paint, brushes, and foam rollers. When I got home I put the first coat on Vanja’s room while crying so much I could barely see the wall.

challenging

emotional

informative

inspiring

mysterious

reflective

medium-paced

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

There is nothing I could write that could possibly do justice to this book, this series of books. I have never read anything like it and I can’t imagine I will again.

This sixth and final volume is 1150 pages long of which roughly 400 are about the early life of Adolf Hitler.

The last section in an excruciatingly intimate telling of his wife’s hospitalization as she is unable to cope with the highs and lows of her disorder.

If you’re looking for sunshine and giggles you might want to try some other book. I’m in the camp that believes this may be one of the greatest works of literature ever committed to print.

This sixth and final volume is 1150 pages long of which roughly 400 are about the early life of Adolf Hitler.

The last section in an excruciatingly intimate telling of his wife’s hospitalization as she is unable to cope with the highs and lows of her disorder.

If you’re looking for sunshine and giggles you might want to try some other book. I’m in the camp that believes this may be one of the greatest works of literature ever committed to print.

Didn't like this installment of My Struggle and couldn't finish. Considering it done.