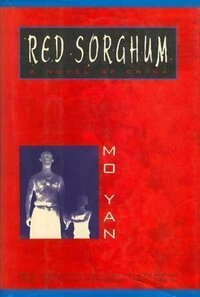

Take a photo of a barcode or cover

adventurous

dark

reflective

sad

tense

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

No

Loveable characters:

No

Diverse cast of characters:

No

Flaws of characters a main focus:

No

adventurous

emotional

reflective

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Plot

Strong character development:

No

Loveable characters:

No

Diverse cast of characters:

No

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

I'd like to put down poor translating as the reason I didn't like this book, but I don't actually think that is the case. The overuse of sorghum and colours as symbolism was heavy-handed, the violence was both tedious and excessive and the parts of the story that were interesting - the inter-generational personal relationships - were told in such a disjointed fashion that it was hard to keep track of.

challenging

dark

emotional

inspiring

reflective

sad

tense

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

A mix

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

If you liked this, I recommend…

- 🏜️ Blood Meridian (more artistic)

- 🕸️ One Hundred Years of Solitude (more surrealistic)

- 🌘 Season of Migration to the North (little violent & more contemplative)

- 🌴 Harp of Burma (gentler & less artistic)

- 🗡️ Waiting for the Barbarians (more intimate & bleak)

- 💀 The Thirteenth House by Zameenzad (even bleaker)

This book has moments that are truly horrifying and sickening, but the force of its fiery and courageous main characters and the poetry of the prose make them a little easier to endure. The narrative’s frequent time-jumping was rather jarring at first, but eventually I grew accustomed to it. And that, I think, is the novel’s greatest quality: it creates its own world entirely.

The phrase “red sorghum” probably occurs hundreds of times, and the analogies are often deeply Chinese or even specific to the setting and narrative. By interweaving the past and future with frequent reference to events of each within the other, it creates a kind of fairytale- or folklore-esque rhythm. This impression is enhanced by the wild and often dark superstitions of the villagers, and the surrealistic army of dogs. The writing style and plot could be vaguely compared to One Hundred Years of Solitude or Blood Meridian, but Yan has his own distinctive voice that is clearer and more personal. (At least once, he even speaks to the reader directly, charging them to make a psychological and moral guess.) Two of the book’s main characters, the narrator’s Grandma and Grandpa, are called heroic at first; over time, they become as such for the reader despite their gross flaws, thanks not only to their actions but also to the narrative’s presentation of them like Greek gods who continually return to the stage (Greek for me; surely like Chinese heroes for those versed in that literature).

There is not one clear message to the book, which is very complex. People’s behavior is strange. Despite the loathsome threat of the Japanese invasion, the various Chinese regiments and bands are constantly at each other’s throats. Maybe that’s how it really was. The horrible acts of the Japanese soldiers would seem to thoroughly stamp the book as an anti-war novel, but it doesn’t seem to condemn violence as such, and most of the male characters are brutal. Nor does it praise it.

In a sense, it feels like not only the Japanese, who appear as inhuman beasts and psychopathic sadists, but almost everyone in the book is blamed—the Chinese characters, mostly not for their violence, but for their follies. At the end, the narrator bemoans the loss of the culture and life of the past, surely likening the red of the sorghum to China before the Second Sino-Japanese War, before the civil war between the Nationalists and Communists, and maybe just…before. The loss of a more natural way of life and the imposition of modernized hybrid sorghum seems key at the end. However, the majority of the book does not describe the loss of a culture the way that Things Fall Apart does—mostly, it describes the waves of battles and love affairs that defined the narrator’s grandparents’ lives, contrasted with their traditional village life whose occasional violence looks like tea and roses compared to the Japanese forces’ violence. This older violence has a quality of “when men were men” and the grandfather’s acts of murder on behalf of the grandmother certainly have a heroic light about them.

Perhaps these complexities are a result of the complexities of the real situation. It’s not simply that China’s civil war and following government changed its character, but also that the Japanese invasion demolished and violated so much. Things Fall Apart may be a good comparison after all: there is much to judge and criticize about the culture prior to the impositions of outsiders and government changes, especially on behalf of women and children; but it was something genuine and personal, something embedding people in nature and steeped in colorful tradition. It was not for outsiders to destroy.

For my part, the main result of reading this novel was to become even more anti-war than I was, though I am not confident this is an anti-war novel (maybe an anti-invasion novel). For the narrator, the Japanese seem to be the prime evil, and truly some of their real-life WWII acts I’ve read about are sickening. But I also have worked as a Japanese translator and lived in Japan, and know that a people cannot be condensed to their wartime behavior, especially not their soldiers’ wartime behavior. How then to reconcile the morally unacceptable behavior of the Japanese soldiers in Red Sorghum with the character of the Japanese people as a whole today? For me, the answer is that war always turns some people into animals. No matter their nation, no matter their race, this is the inevitable result of setting out with the intent to kill as many human beings of a certain color (be it uniform or skin) as possible. To always assign the root cause to the aggressor being “bad” misses the point that as long as war is a viable concept for humanity there will always be aggressors, and often the victims of the past become the perpetrators of the future. I don’t know if there is a single root to all war, despite its many differing motivations, or how war can be ended on Earth; but certainly Red Sorghum made me feel more strongly than ever that it is madness.

Graphic: Gun violence, Sexual violence, Violence

bleakest book i’ve ever read. every character is an ass but also kinda not an ass. i loved them as much as i hated them.

Nice cultural experience into China that spans three generations. It jumps back and forth between the times and may drive the reader crazy.

mo yan is a strange and wonderful writer, and red sorghum is no exception. set in the second sino-japanese war, it follows the narrator's father, grandfather and grandmother and the plight of the villagers around them suffering under japanese occupation. the writing feels woozy and delirious - describing, for example, the fields of red sorghum in flowery detail as well as the decaying corpses of villagers sprawled upon them. its structure is similar in that it doesn't really have a beginning or an end, moving back and forth through time elastically in a disorientating fashion. that, coupled with the hideous and constant violence and death, made this a very potent book but one i increasingly wanted to escape from. if it had ended a 100 pages before it did i would have added on an extra star.

Surprisingly war-based (well, I say surprisingly even though I entered the book knowing nothing other than it'd been on my shelf for 2 years), the writing was good despite the narrow focus. Typically I prefer shorter novels about war and battles since, in my estimation, they tend to get repetitive. But this novel interwove the story of our narrator's grandparents' meeting and 'romance' and coming together. The battle with the dogs was probably the most interesting part of the book (really, it could be quite gory in parts), but my favorite were the early scenes when the narrator's grandmother had been betrothed to a supposed leper.

Weird: there's a "to understand this, you have to understand this other story" structure here - even the generational element - that in the works of T. R. Pearson, I love. This, however...not for me.