Take a photo of a barcode or cover

adventurous

challenging

informative

reflective

medium-paced

informative

reflective

medium-paced

As someone who is California born and bred I could not help but resonate with Didion’s descriptions and misgivings of her native state. Even now 20 years after it’s publication, her examination and deconstruction of Californian’s fantasies about themselves rings still true to this day. While her prose still kept me engaged I did feel that the book had peaks and valleys. Instead of one narrative through line it seemed to meander a bit as she examined various aspects of California from the intensely personal to the more historic. Nevertheless, a really fantastic and essential read for the native Californian who is wondering how and why we got here.

A thought-provoking exploration on the history of California as well as the history of generations of Didion’s ancestors before her. As much as I love Didion’s writing and admire her work, I can truthfully say that I wouldn’t have enjoyed this as much if I wasn’t a California resident. Being a California resident, it was a treat to read about the local places and events mentioned in this book. Regardless, it’s no question that Didion is one of the greatest journalists of all time and it really shines through in this collection.

informative

slow-paced

informative

reflective

slow-paced

challenging

informative

reflective

medium-paced

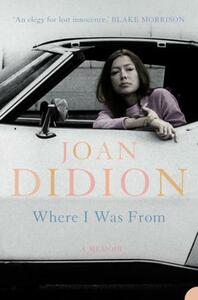

Where I Was From defies genre and structural expectations. Its central theme is Joan Didion’s discomfort with the mythology of California, supposedly the Golden State with a Golden Age, site of the great Gold Rush of the 1840s and 50s and host to great ranches and fields of golden grain. Beneath all this glitter, Didion suggests—beneath boasts of pioneer courage and self-sufficiency and love of the land—there lies a much more complex story.

Or rather, many stories. Each chapter is part historical reporting, part memoir, part political commentary, part literary analysis. Didion references historical events, news reports, speeches, letters, personal memories, novels—even her own first novel from forty years prior—in what seems at first to be a disorientingly disordered fashion. By the book’s midpoint so many subjects have woven in and out of the text that one wonders whether Didion has a cohesive point to make. Only then does she begin to loop back, picking up dropped threads and tying together her many thoughts with delicate connections.

The result is not a cohesive narrative about California. In fact, it’s the opposite: the book demonstrates that there can be no cohesive narrative. Every character in the motley cast has his or her own version of a “true” California, whether it’s found in a romanticized past or an alluring future. There can be no “true” history, only what Didion describes as a shifting hologram of diverse perceptions layered onto the land itself.

In entering and exploring this hologram, Didion takes us beyond the state’s golden mythological self-image. Per her experience and reporting, Californians claim to be fiercely self-sufficient, yet their existence has always relied heavily on federal money (waterworks funding, agricultural subsidies, Department of Defense contracts). Californians pine for some long-faded “authentic” version of the land that has been spoilt by newcomers, failing to note that essentially everyone is a newcomer and everyone has played a role in pushing the region to change beyond recognition from one generation to the next. Californians are hypocritical, even delusional, taken in by narratives that gild over society’s past and present profiteering. (Didion’s “Californians” are apparently only European-Americans; virtually no mention is made of Native Americans or of immigrants of Chinese or Hispanic origin, let alone their experiences and identities within the state.)

In my reading of it, Didion’s dizzying account of California’s evolution reveals universal elements of human nature throughout history. We as a species are wandering, yearning, confused; we are also tough and ruthless. We are interested in survival above all else, and when that is secured then profit above all else. Despite our claims to value community bonds, when faced with difficult times we’re quickly willing to sacrifice each other to save ourselves. This is illustrated by pioneers who abandoned fellow travelers when their wagons failed, or ate them when snowed in at Donner Pass. If that seems too distant, it’s also on display when we institutionalize the mentally ill like prisoners rather than provide treatment, or when we turn petty criminals into lifelong prisoners in the world’s largest private (profitable) prison system.

Didion draws few explicit conclusions in Where I Was From, but her concluding note is one of loss: ultimately we lose everything in life. Landscapes are flooded and razed and developed, traditions evolve out of existence, loved ones pass away. None of this is news to us, of course, nor is it particularly tied to California. But in entering the hologram that is her state’s history, Didion loses her own illusions about her heritage. Over the course of the book’s meandering weave, we witness this loss as if in real time. And by the last page it seems certain that this loss-of-illusions is unavoidable for all of us—another inevitable life loss to add to the list.

Or rather, many stories. Each chapter is part historical reporting, part memoir, part political commentary, part literary analysis. Didion references historical events, news reports, speeches, letters, personal memories, novels—even her own first novel from forty years prior—in what seems at first to be a disorientingly disordered fashion. By the book’s midpoint so many subjects have woven in and out of the text that one wonders whether Didion has a cohesive point to make. Only then does she begin to loop back, picking up dropped threads and tying together her many thoughts with delicate connections.

The result is not a cohesive narrative about California. In fact, it’s the opposite: the book demonstrates that there can be no cohesive narrative. Every character in the motley cast has his or her own version of a “true” California, whether it’s found in a romanticized past or an alluring future. There can be no “true” history, only what Didion describes as a shifting hologram of diverse perceptions layered onto the land itself.

In entering and exploring this hologram, Didion takes us beyond the state’s golden mythological self-image. Per her experience and reporting, Californians claim to be fiercely self-sufficient, yet their existence has always relied heavily on federal money (waterworks funding, agricultural subsidies, Department of Defense contracts). Californians pine for some long-faded “authentic” version of the land that has been spoilt by newcomers, failing to note that essentially everyone is a newcomer and everyone has played a role in pushing the region to change beyond recognition from one generation to the next. Californians are hypocritical, even delusional, taken in by narratives that gild over society’s past and present profiteering. (Didion’s “Californians” are apparently only European-Americans; virtually no mention is made of Native Americans or of immigrants of Chinese or Hispanic origin, let alone their experiences and identities within the state.)

In my reading of it, Didion’s dizzying account of California’s evolution reveals universal elements of human nature throughout history. We as a species are wandering, yearning, confused; we are also tough and ruthless. We are interested in survival above all else, and when that is secured then profit above all else. Despite our claims to value community bonds, when faced with difficult times we’re quickly willing to sacrifice each other to save ourselves. This is illustrated by pioneers who abandoned fellow travelers when their wagons failed, or ate them when snowed in at Donner Pass. If that seems too distant, it’s also on display when we institutionalize the mentally ill like prisoners rather than provide treatment, or when we turn petty criminals into lifelong prisoners in the world’s largest private (profitable) prison system.

Didion draws few explicit conclusions in Where I Was From, but her concluding note is one of loss: ultimately we lose everything in life. Landscapes are flooded and razed and developed, traditions evolve out of existence, loved ones pass away. None of this is news to us, of course, nor is it particularly tied to California. But in entering the hologram that is her state’s history, Didion loses her own illusions about her heritage. Over the course of the book’s meandering weave, we witness this loss as if in real time. And by the last page it seems certain that this loss-of-illusions is unavoidable for all of us—another inevitable life loss to add to the list.

Es mi primera vez leyendo a Didion y la verdad no logré conectar más que en un par de crónicas con algunas quotes e imágenes literarias potentes. De ahí en fuera, hay mucha información política e histórica sobre California y EU que me aburrió bastante y no me aportó mucho literariamente hablando. Espero poder leer algo de la autora en un futuro que me ayude a engancharme. :(

challenging

informative

inspiring

mysterious

reflective

slow-paced

sorry joan didnt like this one too dense for my mood rn