Take a photo of a barcode or cover

Timely and for a younger audience than I've seen the subject presented to before. The text was very simple but conveyed a lot of emotion.

Definitely written for a pre-YA crowd. The topic is important/relevant. but the delivery could’ve been so much better.

dark

emotional

hopeful

reflective

sad

tense

fast-paced

I wanted to like this much more than I did. The premise is intriguing, timely and sad, but the writing was too choppy and dispassionate to do justice to the material. I would certainly keep it in my classroom library, were I teaching, but it won't make the syllabus this semester.

dark

emotional

sad

fast-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Plot

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Yes

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

This book is a fairly quick read about an important topic. I wasn't terribly anxious to read about this topic, as it is too painful right now, with similar events happening far too often. I don't know if it brings resolution to them or not. In a way, the book makes me feel more helpless than ever. The good things that happen are slightly unrealistic and the bad things all too common. In spite of that, I hope this book helps make things slightly better.

Powerful. Could be a tough read for young kids (under 10 or 11) or sensitive readers. Emphasis on remembering the boys and young men lost to violence based on their race - and on making sure these kind of deaths don’t continue.

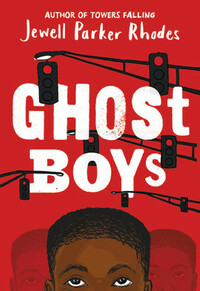

On the rare occasion that twelve year old Jerome is allowed to play outside, a police officer murders him. The jacket copy will say he was “shot by a police officer who mistakes his toy gun for a real threat,” but the novel will not equivocate. You may arrive at the end and understand that the officer is part of a systemic injustice, a consequence of white supremacy, but there will not be any doubt that the police officer murdered a child.

That said, I suppose the copy isn’t misleading for only the sake of non-spoilers. The officer does mistake the toy gun…and the boy’s size, and fails to announce himself. It’s that Jerome doesn’t die immediately, but draws his last painful terrified breaths as the officer stands over him, unmoved and unmoving.

Another uncomfortable aspect is that Jerome doesn’t move on to some happiness or blissful oblivion. He remains as one of thousands of ghost boys. One of these ghost boys is Emmett Till, who appears at Jerome’s side to help him cope. And like Emmett Till’s open casket, all will bear witness to what has and is being done.

Another source of hardship for Jerome is that while his Grandma at least senses him, his parents and younger sister can’t, nor can his only friend Carlos. Sarah can not only sense him, but see and converse with him. Sarah is the white twelve year old daughter of the white police officer who murders Jerome. Yeah, this is a painful realization for everyone. But the novel and Emmett Till will argue that there is a good reason for this. Not only will Sarah provide a different perspective, access to a different contextual facet, but once Sarah can be moved some distance beyond her white fragility and white girl tears, she can use her resources to participate in real, positive change. Jerome’s death exposes other people…and how they participate; she can help with that.

I was having difficulty articulating my thoughts about how Jerome is being asked to relate to Sarah (beyond implementing her as a device), and then I read Kirkus Reviews’ review:

“The novel weaves in how historical and sociopolitical realities come to bear on black families, suggesting what can be done to move the future toward a more just direction—albeit not without somewhat flattening the righteous rage of the African-American community in emphasizing the more palatable universal values of ‘friendship. Kindness. Understanding.’”

The length of the novel cannot accommodate the scope of its righteous rage. But then, it isn’t something the novel need worry about the reader experiencing?? As we move through alternating sections of ALIVE and DEAD, what happened and is happening is never far from our thoughts. The question of “what will happen” is the conflict never far from the novel’s thoughts. As Grandma says, when she learns about the source of the toy gun, “Can’t undo wrong. Can only do our best to make things right.” What heals, what carries us forward? “Friendship. Kindness. Understanding.” The difficulty is how this seems to be the task of both the dead and their surviving family members and community*; especially in light of a court’s decision.

But since this is a novel that all our youth should be reading, the task for carrying us forward can be requested of these young readers as well. And young readers should be reading narratives like Ghost Boys. I think about the librarian Ms. Penny that Sarah interacts with, whose first impulse is “You can research it when you’re older,” in academic settings, in cordoned off Heritage Months. But she “closes her eyes, shakes herself, then sighs. ‘Better to light a candle than curse the darkness.’

‘What’s that mean?’

‘A Chinese proverb. It means I’m going to show you a picture of Emmett Till. I was the same ages as you when I saw it.” (117)

Jewell Parker Rhodes telling of Emmett Till’s death is breathtaking.

Jewell Parker Rhodes is a gift. She writes with wisdom, sensitivity, and serious skill. The novel is spare in prose, heavy in dialog. Ghost Boys moves in and out of harder sequences; a gentle offering, and yet determined to be honest with the horror of reality. She does not look away, and neither will you. She lifts the lid on that casket in that next to last chapter. We see the full humanity and horror.

Jerome’s is a beautiful soul. We’ll only know a small corner of its breadth. JPR won’t allow it to be unremembered or even misremembered. Ghost Boys is a novel that will leave a mark. It will inspire curiosity, a desire to learn more about the boys we’ve lost to similar violence—Jerome Rogers. Tamir Rice. Laquan McDonald. Trayvon Martin. Michael Brown. Jordan Edwards. to name very few. Ghost Boys will inspire a desire to join with those who wish for a world where these lives matter.

“At least until there aren’t any more murders,” answers Emmett. “Until skin color doesn’t matter. Only friendship. Kindess. Understanding.”

“Peace.” That’s my wish, too. (191)

https://contemplatrix.wordpress.com/2019/02/27/jerome/

That said, I suppose the copy isn’t misleading for only the sake of non-spoilers. The officer does mistake the toy gun…and the boy’s size, and fails to announce himself. It’s that Jerome doesn’t die immediately, but draws his last painful terrified breaths as the officer stands over him, unmoved and unmoving.

Another uncomfortable aspect is that Jerome doesn’t move on to some happiness or blissful oblivion. He remains as one of thousands of ghost boys. One of these ghost boys is Emmett Till, who appears at Jerome’s side to help him cope. And like Emmett Till’s open casket, all will bear witness to what has and is being done.

Another source of hardship for Jerome is that while his Grandma at least senses him, his parents and younger sister can’t, nor can his only friend Carlos. Sarah can not only sense him, but see and converse with him. Sarah is the white twelve year old daughter of the white police officer who murders Jerome. Yeah, this is a painful realization for everyone. But the novel and Emmett Till will argue that there is a good reason for this. Not only will Sarah provide a different perspective, access to a different contextual facet, but once Sarah can be moved some distance beyond her white fragility and white girl tears, she can use her resources to participate in real, positive change. Jerome’s death exposes other people…and how they participate; she can help with that.

I was having difficulty articulating my thoughts about how Jerome is being asked to relate to Sarah (beyond implementing her as a device), and then I read Kirkus Reviews’ review:

“The novel weaves in how historical and sociopolitical realities come to bear on black families, suggesting what can be done to move the future toward a more just direction—albeit not without somewhat flattening the righteous rage of the African-American community in emphasizing the more palatable universal values of ‘friendship. Kindness. Understanding.’”

The length of the novel cannot accommodate the scope of its righteous rage. But then, it isn’t something the novel need worry about the reader experiencing?? As we move through alternating sections of ALIVE and DEAD, what happened and is happening is never far from our thoughts. The question of “what will happen” is the conflict never far from the novel’s thoughts. As Grandma says, when she learns about the source of the toy gun, “Can’t undo wrong. Can only do our best to make things right.” What heals, what carries us forward? “Friendship. Kindness. Understanding.” The difficulty is how this seems to be the task of both the dead and their surviving family members and community*; especially in light of a court’s decision.

But since this is a novel that all our youth should be reading, the task for carrying us forward can be requested of these young readers as well. And young readers should be reading narratives like Ghost Boys. I think about the librarian Ms. Penny that Sarah interacts with, whose first impulse is “You can research it when you’re older,” in academic settings, in cordoned off Heritage Months. But she “closes her eyes, shakes herself, then sighs. ‘Better to light a candle than curse the darkness.’

‘What’s that mean?’

‘A Chinese proverb. It means I’m going to show you a picture of Emmett Till. I was the same ages as you when I saw it.” (117)

Jewell Parker Rhodes telling of Emmett Till’s death is breathtaking.

Jewell Parker Rhodes is a gift. She writes with wisdom, sensitivity, and serious skill. The novel is spare in prose, heavy in dialog. Ghost Boys moves in and out of harder sequences; a gentle offering, and yet determined to be honest with the horror of reality. She does not look away, and neither will you. She lifts the lid on that casket in that next to last chapter. We see the full humanity and horror.

Jerome’s is a beautiful soul. We’ll only know a small corner of its breadth. JPR won’t allow it to be unremembered or even misremembered. Ghost Boys is a novel that will leave a mark. It will inspire curiosity, a desire to learn more about the boys we’ve lost to similar violence—Jerome Rogers. Tamir Rice. Laquan McDonald. Trayvon Martin. Michael Brown. Jordan Edwards. to name very few. Ghost Boys will inspire a desire to join with those who wish for a world where these lives matter.

“At least until there aren’t any more murders,” answers Emmett. “Until skin color doesn’t matter. Only friendship. Kindess. Understanding.”

“Peace.” That’s my wish, too. (191)

https://contemplatrix.wordpress.com/2019/02/27/jerome/

I’d been wanting to read this book for quite some time. I’m glad I finally did. I would love to include this in my curriculum somehow.

As a white reader, I hesitate to even try to put my thoughts into words. Clearly this book has struck a chord with many.

I just felt . . . uncomfortable the whole time. And not uncomfortable in the intended way. After the main character's death at the hands of a white police officer, he basically gets to know the ghosts of other murdered Black boys, witnesses his own trial, and has lots of long conversations with the racist cop's daughter.

This could have been great. The idea of depicting the Jerome's death as a cultural pattern of racial violence by introducing him to a cohort of actual ghosts could have worked really well. Some of the scenes were almost moving for me--Jerome grieving his own death alongside hundreds of other boys who have lived the same story was profound.

Unfortunately, with the exception of early scenes where Jerome is actually alive and talking to his sister or his new friend at school, none of the kids actually sound like people. Their whole identities have become "mature, sympathetic prop, gently teaching white people to be less terrible," and that feels, uh, wildly out of place in a book that opens with a child being shot in the back. Can Jerome's adored little sister see him? His friend, wracked with guilt? Nope, of course not. Because at the end of the day, his role in the story is not to heal himself, avenge his own death, connect with his grieving family. His role is to soothe the distraught white girl, worried that maybe her cop father is a Bad Person because he put a bullet in a kid her same exact size.

Look, it truly wasn't her fault her dad did something terrible, and I don't think that Jerome's ability to recognize the awfulness of her situation (I mean, imagine knowing your dad would kill a child!) is somehow wrong. But every time he says something "mean" or "bullying" and then feels rotten about it, he's actually trying to convey a hard truth about inequality that he shouldn't have to apologize for. Why is it this dead boy's job to fix the heart of a little white girl? Why does he have to be so patient with her as she says really insensitive things over and over because she has good intentions or something? Why does this involve her taking on the role of being a "voice" for dead Black boys instead of her confronting racism in her own white communities, a much more appropriate place for her new passion? But no, it's Jerome's job to talk to and fix white people (kindly, gently, softly, understanding that being a cop is really hard and maybe sometimes you just accidentally shoot children) and it's Sarah's job to advocate for the Black community. It all felt very backwards. We hear a lot about Emmett Till and the truth of his murder, a murder instigated by a white woman who pretended to feel very upset by him. We are supposed to like Sarah (and sure, I believe she wouldn't falsely accuse a young Black boy of anything) but the whole book I just kept thinking oh, here are those white woman tears that end up as the center or so many conversations on race. This is like, a primer for that. Jerome simply has no room for his rage or pain or impatience because every time he lets a feeling out, it makes Sarah cry.

All too quickly, Jerome loses his anger. He becomes the perfect saintly martyr, a murdered child who won't even speak a word against the adult man who killed him. We're supposed to believe that his sister is "moving on" and "having fun again" less than a year later. There's little discussion of trauma except for his parents, barely mentioned, who are both shells of themselves, and this is mostly framed as a sad inability on their part to celebrate his life instead of grieving his death.

Most egregiously, the book concludes with Jerome being very concerned about Sarah hating her dad, giving her a pep talk about how she should forgive him for making "one mistake." And then Sarah and her dad hug and cry and her dad says he'll help her make a website to fight racism. Yay, good for you! The whole thing where you lied in court from start to finish, then got off scot-free, almost made me think you didn't actually feel remorse! But that's what white people so often get to do in stories: screw up whenever actually stakes are present, in ways that multiply existing destruction, then at the last second, have a Change of Heart where they're going to do something friendly and progressive going forward that will cost them nothing and not threaten anything they gained by exploiting centuries of racism the whole rest of the book.

I respect that the author seems to value nonviolence, education, and the power of collective awareness to steer a culture away from its past mistakes. But it really feels like as much as this book is tells white people not to stereotype Black boys (and it does say that), it's also admonishing Black readers not to be too hard on the poor white people who are suffering in their own ways, you know, from the crushing guilt of killing children. Maybe there's a place for that kind of incredible empathy; I do believe anyone can change if they choose. But this book simply didn't have room for the amount of nuance necessary to make that stance feel as gritty and well-earned as it needs to feel.

I just felt . . . uncomfortable the whole time. And not uncomfortable in the intended way. After the main character's death at the hands of a white police officer, he basically gets to know the ghosts of other murdered Black boys, witnesses his own trial, and has lots of long conversations with the racist cop's daughter.

This could have been great. The idea of depicting the Jerome's death as a cultural pattern of racial violence by introducing him to a cohort of actual ghosts could have worked really well. Some of the scenes were almost moving for me--Jerome grieving his own death alongside hundreds of other boys who have lived the same story was profound.

Unfortunately, with the exception of early scenes where Jerome is actually alive and talking to his sister or his new friend at school, none of the kids actually sound like people. Their whole identities have become "mature, sympathetic prop, gently teaching white people to be less terrible," and that feels, uh, wildly out of place in a book that opens with a child being shot in the back. Can Jerome's adored little sister see him? His friend, wracked with guilt? Nope, of course not. Because at the end of the day, his role in the story is not to heal himself, avenge his own death, connect with his grieving family. His role is to soothe the distraught white girl, worried that maybe her cop father is a Bad Person because he put a bullet in a kid her same exact size.

Look, it truly wasn't her fault her dad did something terrible, and I don't think that Jerome's ability to recognize the awfulness of her situation (I mean, imagine knowing your dad would kill a child!) is somehow wrong. But every time he says something "mean" or "bullying" and then feels rotten about it, he's actually trying to convey a hard truth about inequality that he shouldn't have to apologize for. Why is it this dead boy's job to fix the heart of a little white girl? Why does he have to be so patient with her as she says really insensitive things over and over because she has good intentions or something? Why does this involve her taking on the role of being a "voice" for dead Black boys instead of her confronting racism in her own white communities, a much more appropriate place for her new passion? But no, it's Jerome's job to talk to and fix white people (kindly, gently, softly, understanding that being a cop is really hard and maybe sometimes you just accidentally shoot children) and it's Sarah's job to advocate for the Black community. It all felt very backwards. We hear a lot about Emmett Till and the truth of his murder, a murder instigated by a white woman who pretended to feel very upset by him. We are supposed to like Sarah (and sure, I believe she wouldn't falsely accuse a young Black boy of anything) but the whole book I just kept thinking oh, here are those white woman tears that end up as the center or so many conversations on race. This is like, a primer for that. Jerome simply has no room for his rage or pain or impatience because every time he lets a feeling out, it makes Sarah cry.

All too quickly, Jerome loses his anger. He becomes the perfect saintly martyr, a murdered child who won't even speak a word against the adult man who killed him. We're supposed to believe that his sister is "moving on" and "having fun again" less than a year later. There's little discussion of trauma except for his parents, barely mentioned, who are both shells of themselves, and this is mostly framed as a sad inability on their part to celebrate his life instead of grieving his death.

Most egregiously, the book concludes with Jerome being very concerned about Sarah hating her dad, giving her a pep talk about how she should forgive him for making "one mistake." And then Sarah and her dad hug and cry and her dad says he'll help her make a website to fight racism. Yay, good for you! The whole thing where you lied in court from start to finish, then got off scot-free, almost made me think you didn't actually feel remorse! But that's what white people so often get to do in stories: screw up whenever actually stakes are present, in ways that multiply existing destruction, then at the last second, have a Change of Heart where they're going to do something friendly and progressive going forward that will cost them nothing and not threaten anything they gained by exploiting centuries of racism the whole rest of the book.

I respect that the author seems to value nonviolence, education, and the power of collective awareness to steer a culture away from its past mistakes. But it really feels like as much as this book is tells white people not to stereotype Black boys (and it does say that), it's also admonishing Black readers not to be too hard on the poor white people who are suffering in their own ways, you know, from the crushing guilt of killing children. Maybe there's a place for that kind of incredible empathy; I do believe anyone can change if they choose. But this book simply didn't have room for the amount of nuance necessary to make that stance feel as gritty and well-earned as it needs to feel.