You need to sign in or sign up before continuing.

Take a photo of a barcode or cover

492 reviews for:

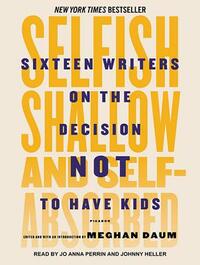

Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed: Sixteen Writers on the Decision Not to Have Kids

Meghan Daum

492 reviews for:

Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed: Sixteen Writers on the Decision Not to Have Kids

Meghan Daum

I enjoyed listening to many voices speak about what is meaningful and important to them. I appreciated the essays that reminded me that whatever decision we come to must consider how parents impact children's lives, not just how children impact theirs.

"Life is such a complex, treacherous matter, so quickly lived and difficult to experience fully precisely because it is so crowded with diversity and choice" (244).

"Life is such a complex, treacherous matter, so quickly lived and difficult to experience fully precisely because it is so crowded with diversity and choice" (244).

Not to be consumed in one sitting, and probably not to be consumed as part of a book club. I imagine its potential to send the most mild-mannered of women storming off in their Euro-comfort sensible shoes. Though several writers in Selfish pose that is exactly the problem -- if more people were willing to at least consider the alternative, then maybe childfree people wouldn't be looked upon so poorly.

Note that I own my fair share of Euro-comfort shoes so no judging there.

Note that I own my fair share of Euro-comfort shoes so no judging there.

While this was fascinating and I agreed with several of the opinions expressed in these essays, I wish there were more younger voices--almost (if not all) these authors were past child-bearing age, and their choices to not have children were half planned, half "whoops, it's too late now, but I guess it's for the best."

I read this to get perspective from people who don't want kids, since I don't have that many people in my life who have explicitly stated that they don't want kids. I really enjoyed the variety of perspectives in the collection. One thing that was kind of off-putting was that there seemed to be a thread of bitterness/anger running through all of the writers' essays, but this could have been something I noticed because they are writing about views that are quite opposite to mine on the issue of parenthood. Also, several writers did mention having to keep explaining their choice to friends and family and random strangers, which would make anyone sound bitter after a while.

Mixed feelings about this book. I picked it for Read Harder (essay anthology), but I happened to be reading it when I got some bad financial news and suddenly I was questioning my intention to have kids. There are some good points in this collection, but I think the editor ordered in such a way that it ends with a couple highly unlikeable essays and one that is oddly hopeful.

challenging

funny

reflective

sad

medium-paced

3.5 stars. I’ll file this one away with books like [b:Crime and Punishment|7144|Crime and Punishment|Fyodor Dostoyevsky|https://d.gr-assets.com/books/1382846449s/7144.jpg|3393917], [b:Gone with the Wind|18405|Gone with the Wind|Margaret Mitchell|https://d.gr-assets.com/books/1328025229s/18405.jpg|3358283], [b:American Savage|16101100|American Savage Insights, Slights, and Fights on Faith, Sex, Love, and Politics|Dan Savage|https://d.gr-assets.com/books/1353100051s/16101100.jpg|21911401], and plays like “Rent” that help expand my thinking and build my empathy muscles without actually changing the core of what feels right and true for my own life. (Meaning yes, I’m still interested in having children, thanks for asking.) My favorite essay was the closing one by the fabulous and droll Tim Kreider. If I can borrow from his previous work, [b:We Learn Nothing|13259887|We Learn Nothing|Tim Kreider|https://d.gr-assets.com/books/1344396590s/13259887.jpg|18461390], he says:

What bothered me about Shriver’s essay was the way she wants to be “allowed” to feel sad about the educated white population declining in dominance in America, as if institutionalized privilege hasn’t always allowed white people, men in particular, to have outsized power and influence relative to their numbers—and as if this won’t continue to be true long after they/we have stopped being the demographic majority. I get what she’s saying about feeling like a lot of the people who end up having children are not necessarily the folks best equipped to do so, financially or otherwise. And sure, change can be instinctively unsettling; a knee-jerk reaction sort of makes sense if you feel your cultural hegemony is threatened. But I expected Shriver to be more insightful and nuanced than that. Of all the reasons to be bothered by not having children, failing to propagate the population of European Americans just does not resonate with me in the 21st century. It’s a bad proxy for whatever’s really bothering her. Or maybe I’m just really naive and she is being that racist, openly.

So on the whole, a worthy and thought-provoking read. As the editor herself noted in the introduction, this compilation suffers a bit for its lack of diversity; there was quite a bit of repetition across essays and some voices were certainly missing. It was also surprisingly humorless until the end. Nonetheless, a good addition to the conversation that we’re not really having.

“One reason we rush so quickly to the vulgar satisfactions of judgment, and love to revel in our righteous outrage, is that it spares us from the impotent pain of empathy, and the harder, messier work of understanding.”That’s a pretty good summary of what this book is trying to combat. Both the men and the women who wrote essays for this anthology highlighted the cultural implications of childlessness, with most—including the men—noting that women are particularly hard-hit by accusations of selfishness and brokenness, as if they must be borderline pathological not to want children. There was plenty of childhood sadness to go around in this volume, but that’s probably true if you pull together any group of sixteen adults, parents or not. As Danielle Henderson said,

“A lot of people who had terrible childhoods have kids to prove that they can do a better job, or to fix some cosmic rift by being the parents they needed to their own children. I sometimes wonder why I fall into the category of people who responded to their own crappy childhoods by never wanting to have kids. It’s possible that I’m not very brave; you have to have a lot of hope and faith that you’ve somehow learned everything your family was supposed to teach you but didn’t. You have to tell yourself you’ll be able to avoid the pitfalls you grew up with. But, even then, you create new pitfalls. I negotiate the terms of my life every day and work hard to maintain an emotional status quo that I had to create from scratch. That’s hard to do with a child in tow.” (p. 156-57)I come down pretty hard siding with Henderson that “selfish” is not a word that applies to that kind of choice. Conversely, imposing your own unresolved issues on a child who didn’t ask for them is hardly the image of selflessness. She goes on:

“I admire women who look at the rigors of parenting and decide they’re just not cut out for it, or just don’t want to try, and I wish that we had more conversations about childlessness that didn’t force us to approach them from such a defensive place. I’m also sensitive to the fact that there are plenty of women in the world who want children and are unable to have them naturally, or women who have miscarried, often more than once, on their journey to parenthood. It seems hostile and uncaring to have a conversation about motherhood that is rooted in selfishness when so many women are unable to walk down that road.” (p. 158-59)For as many times as I found myself nodding along in agreement, as with Henderson, there was a lot here that gave me real pause. A couple of these essays were upsetting (I’m looking at you, Lionel Shriver!) but worth reading anyway because they’re honest. Speaking your own ugly truth is hardly the worst thing an author can do. Actually, that’s probably why we need authors.

What bothered me about Shriver’s essay was the way she wants to be “allowed” to feel sad about the educated white population declining in dominance in America, as if institutionalized privilege hasn’t always allowed white people, men in particular, to have outsized power and influence relative to their numbers—and as if this won’t continue to be true long after they/we have stopped being the demographic majority. I get what she’s saying about feeling like a lot of the people who end up having children are not necessarily the folks best equipped to do so, financially or otherwise. And sure, change can be instinctively unsettling; a knee-jerk reaction sort of makes sense if you feel your cultural hegemony is threatened. But I expected Shriver to be more insightful and nuanced than that. Of all the reasons to be bothered by not having children, failing to propagate the population of European Americans just does not resonate with me in the 21st century. It’s a bad proxy for whatever’s really bothering her. Or maybe I’m just really naive and she is being that racist, openly.

So on the whole, a worthy and thought-provoking read. As the editor herself noted in the introduction, this compilation suffers a bit for its lack of diversity; there was quite a bit of repetition across essays and some voices were certainly missing. It was also surprisingly humorless until the end. Nonetheless, a good addition to the conversation that we’re not really having.

I received this book from Netgalley in exchange for an honest review.

I don't want children.

At my age, however, this statement is usually met with the response of, "Oh, but you're so young. You'll change your mind."

This is not only condescending, but inaccurate (which honestly bothers me more). Not every woman is built to be a mother. Children can be great, sure. But I've never been one to "ooh" and "ahh" over baby pictures, find myself unable to resist pinching baby cheeks, or feel the desire to babysit just to spend an afternoon enjoying a child's company.

In many ways, I wish that was me. We're told that it's natural to desire family life, to want to hold a baby in your arms and experience the torrential downpour of hormonal affection. Like one essayist in this collection explicitly states, I want to want to be a mother.

But beyond the fact that the magic of children has always eluded me, there have always been a thousand reasons why I've thought I shouldn't have them. Most of those reasons are skillfully articulated in this collection (it is, after all, a compilation of essays by professional writers).

The essay that reached me the most was the one by Jeanne Safer. She criticizes the notion of "having it all"; it is simply not possible to have it all. We all give up certain possibilities in exchange for a different set of experiences and there is no life without regret. As an extreme realist, this was refreshingly honest to me. To have children means giving up a life without them, or, giving up the freedom that a childfree existence allows.

More and more people (in the Western world, at least) are choosing not to have children, and I think this work gives a good sample of the reasons why one reaches that decision. I found each and every essay fascinating and identified with at least one idea in each of them. Parenthood is never attacked. Thus, this is a book that would not only appeal to those (like myself) who know they never want children, but also to those who cannot understand why being childfree would be a choice someone would want to make.

I don't want children.

At my age, however, this statement is usually met with the response of, "Oh, but you're so young. You'll change your mind."

This is not only condescending, but inaccurate (which honestly bothers me more). Not every woman is built to be a mother. Children can be great, sure. But I've never been one to "ooh" and "ahh" over baby pictures, find myself unable to resist pinching baby cheeks, or feel the desire to babysit just to spend an afternoon enjoying a child's company.

In many ways, I wish that was me. We're told that it's natural to desire family life, to want to hold a baby in your arms and experience the torrential downpour of hormonal affection. Like one essayist in this collection explicitly states, I want to want to be a mother.

But beyond the fact that the magic of children has always eluded me, there have always been a thousand reasons why I've thought I shouldn't have them. Most of those reasons are skillfully articulated in this collection (it is, after all, a compilation of essays by professional writers).

The essay that reached me the most was the one by Jeanne Safer. She criticizes the notion of "having it all"; it is simply not possible to have it all. We all give up certain possibilities in exchange for a different set of experiences and there is no life without regret. As an extreme realist, this was refreshingly honest to me. To have children means giving up a life without them, or, giving up the freedom that a childfree existence allows.

More and more people (in the Western world, at least) are choosing not to have children, and I think this work gives a good sample of the reasons why one reaches that decision. I found each and every essay fascinating and identified with at least one idea in each of them. Parenthood is never attacked. Thus, this is a book that would not only appeal to those (like myself) who know they never want children, but also to those who cannot understand why being childfree would be a choice someone would want to make.

hopeful

informative

reflective

medium-paced