Take a photo of a barcode or cover

informative

medium-paced

A 2017 poll from the University of Pennsylvania's Annenberg Public Policy Center essentially found that many (or most) Americans know next to nothing about the US Constitution. Two shocking examples should suffice to get the point across:

1. 37 percent of those surveyed could not name ANY rights protected under the First Amendment.

2. Only 26 percent of those surveyed could name all three branches of government, while 33 percent could not name a single branch!!

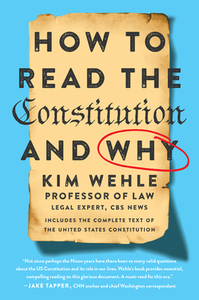

It is against this backdrop of utter ignorance that How to Read the Constitution And Why by Kim Wehle is so important. Wehle, a law professor and constitutional scholar, seeks to remedy a deep irony in American politics: that the Constitution is useless if not enforced, but that it can’t be enforced if the people it grants power to (“We the People”) do not know anything about what it says.

We can’t hold our elected representatives accountable to a document we don’t understand, and if it gets violated, or ultimately replaced, we really have no one to blame but ourselves for tolerating the transgressions. Democracy simply can’t work if it remains the case that 33 percent of the voting population can’t name a branch of government.

The first step to repairing democracy, then, is probably educational, and, of course, it is the responsibility of every citizen to understand, at a minimum, the basic contents of their country’s founding document. Of course, that requires that one actually reads the Constitution itself, and you should, because it’s only only 7,591 words including the 27 amendments (that’s only about 16 pages, so there’s really no excuse). But to truly understand constitutional issues requires something more than a quick reading of the text.

Why? Because again, the document is only about 16 pages long, written 230 years ago, when the US population was 3.9 million (versus 327 million today), in an agrarian economy without advanced technology and 100 years before the discovery of the germ theory of disease. That is to say, things were very different back then, and on top of that, the text is loaded with ambiguous language and missing details. To really understand constitutional issues requires both a familiarity with the Constitution and with the history of important Supreme Court decisions, general US history, and the underlying political political philosophy and legal theory.

But that is probably a tall order for most, which is why How to Read the Constitution and Why provides an ideal shortcut to constitutional fluency without needing to become a legal scholar, historian, or political philosopher.

The organization of the book is easy to follow: the first section covers the structure of government, including the concepts of the separation of powers and checks and balances and the functions of all three branches of government (which will apparently come as news to 33 percent of the country). The second section covers individual rights protected under the constitutional Amendments, and the third section covers elections, the legislative process, and why we should care if the Constitution gets violated and democracy suffers.

Wehle covers the constitutional text, the relevant Supreme Court cases, and the underlying philosophical and legal complexities in an objective and informative manner. The book also includes the full text of the Constitution itself, so as a stand-alone guide, this book is perfect both for those who can’t name a single branch of government as well as for those wanting to dive deeper into the complexities of the law.

Two important themes found throughout the book are worth repeating: 1) any constitutional violations set precedent for future violations, and 2) the “strict reading” of the Constitution is a myth.

First, regarding violations, people tend to be quite short-sighted. You may not mind if the leader you like violates the Constitution according to politics you agree with, but the problem is, once power is granted, it's hard to put back in the bag. So the next time a leader comes to power that you don’t like, he or she will use the established mechanisms to implement policies that run counter to your beliefs. This spells disaster in the long run for everyone.

Protecting the Constitution is therefore not exclusive to one political party or ideology, and should be a concern of everyone. And while it is often not immediately clear if a particular action or piece of legislation in fact violates the Constitution, certain principles should be perpetually upheld. Remember that the Constitution was created in opposition to the monarchical rule of King George III, so any increase in the power of the president, especially in the creation of new laws, should draw an immediate red flag.

Second, to show how the strict reading of the Constitution is a myth, let’s take the non-controversial example of the Second Amendment, which reads:

“A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

One thing we can say is that no one really knows what the fuck this means. This is the entirety of the Second Amendment, with no further elaboration in the Constitution as to the precise meaning of the term “arms” or with any further elaboration on intent, justification, or limitation.

There are consequently at least two primary interpretations to this amendment:

1. That there are two rights being granted, 1) the right for states to form a well regulated Militia, and 2) the right of the people to keep and bear arms. In other words, the right to keep and bear arms is not out of necessity connected to the establishment of a Militia.

2. That the right being granted is the right to form a Militia, and that the right to keep and bear arms applies only within the context of the Militia. (The Second Amendment, if written like the First Amendment, could have just stated that Congress shall pass no laws infringing on the right of the people to keep and bear arms, without mentioning the Militia, if that was the true intention.)

Nonetheless, judges must choose one of these competing interpretations, but either way, it’s an interpretation that is most certainly not spelled out in the Constitution. Further, a true “originalist” interpretation of the term “arms” would not include any firearm that was not in existence on or before 1787 (basically anything other than muskets).

And so every judge must select a general interpretation including decisions on the precise meanings of terms and phrases, and therefore the distinction between “originalist” and “activist” judges is largely a false dichotomy. More important is having a clear rationale for a ruling than to pretend to know the original intentions of the framers, especially when some of the intentions are worth overturning (the condoning of slavery, as one example).

This is all to say that constitutional law is complicated, a balancing act between original intentions and modifications to reflect new realities, but it doesn’t help to hide behind an originalist position that is usually just justification to pursue a conservative ideology without having to spell out the rationale.

----

If you take away anything from the book, as Wehle stated, it should be that the Constitution is worthless if not enforced. And it’s certainly worth enforcing, because if it’s replaced, we can all be reasonably sure that it will be replaced with something far inferior.

1. 37 percent of those surveyed could not name ANY rights protected under the First Amendment.

2. Only 26 percent of those surveyed could name all three branches of government, while 33 percent could not name a single branch!!

It is against this backdrop of utter ignorance that How to Read the Constitution And Why by Kim Wehle is so important. Wehle, a law professor and constitutional scholar, seeks to remedy a deep irony in American politics: that the Constitution is useless if not enforced, but that it can’t be enforced if the people it grants power to (“We the People”) do not know anything about what it says.

We can’t hold our elected representatives accountable to a document we don’t understand, and if it gets violated, or ultimately replaced, we really have no one to blame but ourselves for tolerating the transgressions. Democracy simply can’t work if it remains the case that 33 percent of the voting population can’t name a branch of government.

The first step to repairing democracy, then, is probably educational, and, of course, it is the responsibility of every citizen to understand, at a minimum, the basic contents of their country’s founding document. Of course, that requires that one actually reads the Constitution itself, and you should, because it’s only only 7,591 words including the 27 amendments (that’s only about 16 pages, so there’s really no excuse). But to truly understand constitutional issues requires something more than a quick reading of the text.

Why? Because again, the document is only about 16 pages long, written 230 years ago, when the US population was 3.9 million (versus 327 million today), in an agrarian economy without advanced technology and 100 years before the discovery of the germ theory of disease. That is to say, things were very different back then, and on top of that, the text is loaded with ambiguous language and missing details. To really understand constitutional issues requires both a familiarity with the Constitution and with the history of important Supreme Court decisions, general US history, and the underlying political political philosophy and legal theory.

But that is probably a tall order for most, which is why How to Read the Constitution and Why provides an ideal shortcut to constitutional fluency without needing to become a legal scholar, historian, or political philosopher.

The organization of the book is easy to follow: the first section covers the structure of government, including the concepts of the separation of powers and checks and balances and the functions of all three branches of government (which will apparently come as news to 33 percent of the country). The second section covers individual rights protected under the constitutional Amendments, and the third section covers elections, the legislative process, and why we should care if the Constitution gets violated and democracy suffers.

Wehle covers the constitutional text, the relevant Supreme Court cases, and the underlying philosophical and legal complexities in an objective and informative manner. The book also includes the full text of the Constitution itself, so as a stand-alone guide, this book is perfect both for those who can’t name a single branch of government as well as for those wanting to dive deeper into the complexities of the law.

Two important themes found throughout the book are worth repeating: 1) any constitutional violations set precedent for future violations, and 2) the “strict reading” of the Constitution is a myth.

First, regarding violations, people tend to be quite short-sighted. You may not mind if the leader you like violates the Constitution according to politics you agree with, but the problem is, once power is granted, it's hard to put back in the bag. So the next time a leader comes to power that you don’t like, he or she will use the established mechanisms to implement policies that run counter to your beliefs. This spells disaster in the long run for everyone.

Protecting the Constitution is therefore not exclusive to one political party or ideology, and should be a concern of everyone. And while it is often not immediately clear if a particular action or piece of legislation in fact violates the Constitution, certain principles should be perpetually upheld. Remember that the Constitution was created in opposition to the monarchical rule of King George III, so any increase in the power of the president, especially in the creation of new laws, should draw an immediate red flag.

Second, to show how the strict reading of the Constitution is a myth, let’s take the non-controversial example of the Second Amendment, which reads:

“A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

One thing we can say is that no one really knows what the fuck this means. This is the entirety of the Second Amendment, with no further elaboration in the Constitution as to the precise meaning of the term “arms” or with any further elaboration on intent, justification, or limitation.

There are consequently at least two primary interpretations to this amendment:

1. That there are two rights being granted, 1) the right for states to form a well regulated Militia, and 2) the right of the people to keep and bear arms. In other words, the right to keep and bear arms is not out of necessity connected to the establishment of a Militia.

2. That the right being granted is the right to form a Militia, and that the right to keep and bear arms applies only within the context of the Militia. (The Second Amendment, if written like the First Amendment, could have just stated that Congress shall pass no laws infringing on the right of the people to keep and bear arms, without mentioning the Militia, if that was the true intention.)

Nonetheless, judges must choose one of these competing interpretations, but either way, it’s an interpretation that is most certainly not spelled out in the Constitution. Further, a true “originalist” interpretation of the term “arms” would not include any firearm that was not in existence on or before 1787 (basically anything other than muskets).

And so every judge must select a general interpretation including decisions on the precise meanings of terms and phrases, and therefore the distinction between “originalist” and “activist” judges is largely a false dichotomy. More important is having a clear rationale for a ruling than to pretend to know the original intentions of the framers, especially when some of the intentions are worth overturning (the condoning of slavery, as one example).

This is all to say that constitutional law is complicated, a balancing act between original intentions and modifications to reflect new realities, but it doesn’t help to hide behind an originalist position that is usually just justification to pursue a conservative ideology without having to spell out the rationale.

----

If you take away anything from the book, as Wehle stated, it should be that the Constitution is worthless if not enforced. And it’s certainly worth enforcing, because if it’s replaced, we can all be reasonably sure that it will be replaced with something far inferior.

Honestly a pretty good resource if you are not up to speed on how the constitution actually works and what is said within it. Talks about inconsistancies in language and how there cannot really be a 'true' read of this document as a lot of it must be interpreted.

informative

medium-paced

This is a great guide to what a) the Constitution actually says and b) how the text has been interpreted over the last few centuries. It dispels common myths, traces legislative, judicial, and executive trends, and outlines the current and future threats to the Constitution's continued viability. She makes an incredibly compelling case for safeguarding the Constitution in an era when Americans take its protections for granted, while concurrently embracing anti-Constitutional and anti-democratic rhetoric with open arms.

What is interesting here is that for a people who are deliriously proud of being the world's oldest democracy, many, if not most, American institutions are fundamentally undemocratic. While we've been content to count on political etiquette and social norms to guard against the worst abuses that can come about from these institutions, Wehle charts how complacent the American public has become, and how little Constitutional protections actually matter if they are not enforced by Americans of any and all political leanings. This is a must-read for concerned citizens--guess what, it's not just you and you're not crazy; our political institutions actually have become wildly partisan, unproductive, and dangerous to democracy over the last generation.

I listened to the audiobook, which is read by the author, but I think readers should go for the print on this one. The outlining of case law is probably better understood in text.

What is interesting here is that for a people who are deliriously proud of being the world's oldest democracy, many, if not most, American institutions are fundamentally undemocratic. While we've been content to count on political etiquette and social norms to guard against the worst abuses that can come about from these institutions, Wehle charts how complacent the American public has become, and how little Constitutional protections actually matter if they are not enforced by Americans of any and all political leanings. This is a must-read for concerned citizens--guess what, it's not just you and you're not crazy; our political institutions actually have become wildly partisan, unproductive, and dangerous to democracy over the last generation.

I listened to the audiobook, which is read by the author, but I think readers should go for the print on this one. The outlining of case law is probably better understood in text.

informative

slow-paced

informative

medium-paced

informative

inspiring

reflective

tense

medium-paced

very good.

not really likd audience...I help people learn the subject for the bar and this id more for an intelligence lay audience ( not one called the team's ConLae subject matter expert...I know this material).

but great for the right audience! well-written, clear but not condescending, covers enough but not overwhelming.

It's notable that the past 5y have been BUSY in some of these areas, so there are changes. And I do think her opinions show...but I also don't think she suggests she's completely neutral on some topics either

i hope I get to work w her one day bc she's a talented teacher of a tricky subject

not really likd audience...I help people learn the subject for the bar and this id more for an intelligence lay audience ( not one called the team's ConLae subject matter expert...I know this material).

but great for the right audience! well-written, clear but not condescending, covers enough but not overwhelming.

It's notable that the past 5y have been BUSY in some of these areas, so there are changes. And I do think her opinions show...but I also don't think she suggests she's completely neutral on some topics either

i hope I get to work w her one day bc she's a talented teacher of a tricky subject

There was a lot of detail I didn't absorb while listening to this book in my in car, but it was very timely in explaining why Americans should be concerned about government upholding the Constitution, whether it's your "side" in power or not: tools that enter a President's toolbox get passed down to every subsequent President. If your guy changes the rules, so can the guy after him.

I really enjoyed this book. It was like the Constitution for Dummies in the best way possible. The information was clear and easy to understand with her use of relevant examples. I wish the section “Why Care” was longer but that’s just a personal preference. Overall, a really great read and an important topic! Everyone should be reading books like this.

informative

slow-paced