Take a photo of a barcode or cover

759 reviews for:

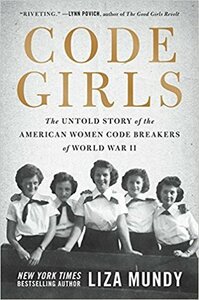

Code Girls: The Untold Story of the American Women Code Breakers Who Helped Win World War II

Liza Mundy

759 reviews for:

Code Girls: The Untold Story of the American Women Code Breakers Who Helped Win World War II

Liza Mundy

adventurous

informative

inspiring

medium-paced

These women are badasses!

informative

My second WW2 book in a short while - am I entering my boomer phase?

adventurous

informative

inspiring

slow-paced

This book was interesting and very easy to listen to. The stories of the individual women were so cool to hear…in particular the main story of Dot Braden and Crow Weston was so sweet! These women remained friends for the rest of their lives after the war! Honestly, parts of this made me emotional because of just how brave and badass these ladies were. I think, also, because many of the women who became Army and Navy code breakers were former teachers (the only career choice for educated women…and they were still underpaid), so I could totally understand why they would jump at this chance. Recommend!!

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️✨(4.5 stars)

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️✨(4.5 stars)

Most people like me know the story of Alan Turing, and of the women who ran the machinery (literal and figurative) of codebreaking that he helped build at Bletchley Park during the second world war. There was, of course, a similar operation on the American side of the Atlantic, also largely staffed by women, for similar reasons: All the men were needed on the front, and anyway, the work was meticulous and tedious, drudgework for which women were supposedly better suited than men, amirite folks?

In fact there were two major operations, one run by the Army and one run by the Navy, and they created thousands of opportunities for women who in peacetime were told that girls weren’t any good at math and shouldn’t waste their time on higher education, yet whose skills in mathematics and foreign languages were suddenly invaluable to their country in wartime. These women did vital work, meticulous and tedious work that also required a healthy share of genius and insight. And of course the work was top secret, and remained so for long after the streamers were swept away behind the last V-J day parade—and therefore never had to be acknowledged by the male establishment that controlled wartime and (more importantly) postwar, narratives about what kinds of contributions women could and should make to American society.

Liza Mundy has done a great deal of research for Code Girls, which is an engaging and often moving account of the work and lives of women in these services. Though the book ranges from the dawn of American cryptographic work through the end of WWII, relying on declassified records and oral histories taken within the NSA and its predecessor agencies, Mundy returns frequently to the lives of a handful of women whom she was personally able to interview, women who were well into their 90s by the time Mundy spoke to them. When the exigencies of war increased the urgency of codebreaking, and the Army operation saw the need to begin hiring women for the work en masse, they turned to elite women’s colleges for their first wave of recruits. (As a Seven Sisters graduate myself, I admit to feeling a frisson of pride every time my alma mater is mentioned in the book. Bryn Mawr women were all over these operations.) The early rounds of Navy recruitment focused on women’s colleges outside the northeast, like Goucher and Sweet Briar. Later, both services recruited heavily from teachers’ colleges; Mundy talks at some length about how the miserable and underpaid work of teaching was one of the few professional careers available to women, and how thrilled so many of them were to have the opportunity to do something else with their sharp, eager minds.

Later, as the Army and Navy opened their ranks to women (to a certain degree), the civilian women who already worked for these operations were able to join the WACs and WAVES, respectively, and further recruitment occurred in the other direction, with leadership identifying talented women in the ranks of those services and bringing them into codebreaking. Mundy therefore gives some pretty interesting contextual digressions into the history of the WACs and WAVES, their relationship to their respective parent forces, and the lives of the women who served in them.

By the end of the war there were thousands of women—both military and civilians—cracking and translating the communications of the German military, the Japanese military, Japanese diplomatic services, and many other coded transmissions. Mundy is as interested in the lives of these women as she is in their work, and paints a lively and well-rounded picture of them, their skills, dreams, fears, and experiences. And unlike Denise Kiernan’s rather sanitized [b:The Girls of Atomic City|15801668|The Girls of Atomic City The Untold Story of the Women Who Helped Win World War II|Denise Kiernan|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1352912866l/15801668._SX50_.jpg|21525054], about the women who worked in the uranium-refining operation in Oak Ridge, Mundy acknowledges that some of the codebreakers had sex—even, occasionally, with one another. These were thousands of healthy young women, after all, not patriotic automata, and every recognition of that makes the book feel more like history and less like cheerful propaganda, though Mundy (like Kiernan) is fairly uncritical of the American war effort in general.

As to the work of codebreaking, Mundy delves into some technical detail, which I have mixed feelings about. On the one hand, I would have liked more—detailed demonstrations with examples of exactly how certain codes were broken, akin to the technical depth of Margalit Fox’s marvelous book about the decipherment of Linear B, [b:The Riddle of the Labyrinth|16240783|The Riddle of the Labyrinth The Quest to Crack an Ancient Code|Margalit Fox|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1387149271l/16240783._SY75_.jpg|24585584]. On the other hand, I read Code Girls in audio form, and so any such technical detail would have literally gone in one ear and out the other—I would have needed to see it written out to fully grasp it. Indeed, because I listened to the book, I can’t fairly critique Mundy’s technical explanations—I might have found them more satisfying if I had read them with my eyes.

The one rather glaring gap in the book is the contributions of Black workers to the codebreaking efforts. Mundy acknowledges the segregation and discrimination that existed despite Roosevelt’s orders that Black people be hired into federal service. But this is mentioned rather in passing, with a brief description of one Black codebreaking unit—also nearly all women—that worked on commercial codes. It’s possible that Mundy simply didn’t have source materials to dig deeply into any of those women’s lives (as Kiernan was able to do in Atomic City, exposing the great inequity Black workers experienced in housing, pay, and work opportunities), but nevertheless the omission stands out.

In fact there were two major operations, one run by the Army and one run by the Navy, and they created thousands of opportunities for women who in peacetime were told that girls weren’t any good at math and shouldn’t waste their time on higher education, yet whose skills in mathematics and foreign languages were suddenly invaluable to their country in wartime. These women did vital work, meticulous and tedious work that also required a healthy share of genius and insight. And of course the work was top secret, and remained so for long after the streamers were swept away behind the last V-J day parade—and therefore never had to be acknowledged by the male establishment that controlled wartime and (more importantly) postwar, narratives about what kinds of contributions women could and should make to American society.

Liza Mundy has done a great deal of research for Code Girls, which is an engaging and often moving account of the work and lives of women in these services. Though the book ranges from the dawn of American cryptographic work through the end of WWII, relying on declassified records and oral histories taken within the NSA and its predecessor agencies, Mundy returns frequently to the lives of a handful of women whom she was personally able to interview, women who were well into their 90s by the time Mundy spoke to them. When the exigencies of war increased the urgency of codebreaking, and the Army operation saw the need to begin hiring women for the work en masse, they turned to elite women’s colleges for their first wave of recruits. (As a Seven Sisters graduate myself, I admit to feeling a frisson of pride every time my alma mater is mentioned in the book. Bryn Mawr women were all over these operations.) The early rounds of Navy recruitment focused on women’s colleges outside the northeast, like Goucher and Sweet Briar. Later, both services recruited heavily from teachers’ colleges; Mundy talks at some length about how the miserable and underpaid work of teaching was one of the few professional careers available to women, and how thrilled so many of them were to have the opportunity to do something else with their sharp, eager minds.

Later, as the Army and Navy opened their ranks to women (to a certain degree), the civilian women who already worked for these operations were able to join the WACs and WAVES, respectively, and further recruitment occurred in the other direction, with leadership identifying talented women in the ranks of those services and bringing them into codebreaking. Mundy therefore gives some pretty interesting contextual digressions into the history of the WACs and WAVES, their relationship to their respective parent forces, and the lives of the women who served in them.

By the end of the war there were thousands of women—both military and civilians—cracking and translating the communications of the German military, the Japanese military, Japanese diplomatic services, and many other coded transmissions. Mundy is as interested in the lives of these women as she is in their work, and paints a lively and well-rounded picture of them, their skills, dreams, fears, and experiences. And unlike Denise Kiernan’s rather sanitized [b:The Girls of Atomic City|15801668|The Girls of Atomic City The Untold Story of the Women Who Helped Win World War II|Denise Kiernan|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1352912866l/15801668._SX50_.jpg|21525054], about the women who worked in the uranium-refining operation in Oak Ridge, Mundy acknowledges that some of the codebreakers had sex—even, occasionally, with one another. These were thousands of healthy young women, after all, not patriotic automata, and every recognition of that makes the book feel more like history and less like cheerful propaganda, though Mundy (like Kiernan) is fairly uncritical of the American war effort in general.

As to the work of codebreaking, Mundy delves into some technical detail, which I have mixed feelings about. On the one hand, I would have liked more—detailed demonstrations with examples of exactly how certain codes were broken, akin to the technical depth of Margalit Fox’s marvelous book about the decipherment of Linear B, [b:The Riddle of the Labyrinth|16240783|The Riddle of the Labyrinth The Quest to Crack an Ancient Code|Margalit Fox|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1387149271l/16240783._SY75_.jpg|24585584]. On the other hand, I read Code Girls in audio form, and so any such technical detail would have literally gone in one ear and out the other—I would have needed to see it written out to fully grasp it. Indeed, because I listened to the book, I can’t fairly critique Mundy’s technical explanations—I might have found them more satisfying if I had read them with my eyes.

The one rather glaring gap in the book is the contributions of Black workers to the codebreaking efforts. Mundy acknowledges the segregation and discrimination that existed despite Roosevelt’s orders that Black people be hired into federal service. But this is mentioned rather in passing, with a brief description of one Black codebreaking unit—also nearly all women—that worked on commercial codes. It’s possible that Mundy simply didn’t have source materials to dig deeply into any of those women’s lives (as Kiernan was able to do in Atomic City, exposing the great inequity Black workers experienced in housing, pay, and work opportunities), but nevertheless the omission stands out.

This was so good! I loved it. I wish there was more information on the lesbians but that wasn't really important to the narrative. I just like that.

emotional

informative

inspiring

medium-paced

Interesting history well told with intimate details. Makes me wish I knew what my grandmother was doing at that time.

Moderate: Sexism, War

At first, I thought the narrator for the audio book had a delivery that was Too Excited. I switched to print, but history books do tend to be a bit dry, and then I saw the advantage of a narrator that adds a little excitement.

Print would be better, perhaps, for the parts where she gives the sequences, if you want to see if you can discern the pattern.

Print would be better, perhaps, for the parts where she gives the sequences, if you want to see if you can discern the pattern.

adventurous

inspiring

reflective

slow-paced