Take a photo of a barcode or cover

challenging

emotional

funny

reflective

tense

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Diverse cast of characters:

No

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

The text is at times laborious and pedantic but manages to accomplish everything one hopes “Infinite Jest” is going to be.

We are not always aware of it, but we try to build our lives in such a way that we avoid the mistakes our parents made (or what we perceive to be their 'mistakes'). This appears to be a futile intention: even if we manage to walk a different path, this results ultimately in a series of other errors. The human condition, you know.

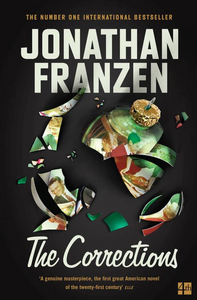

To me this looks like the red line in this novel 'The Corrections' by Jonathan Franzen, though he also plays with other contexts in which the word “correction” is relevant (a correction on the stock exchange for example).

Franzen focuses on an average family in the Midwest of the United States, the Lamberts. The five members of this member are so obsessed by "correcting" their lives, that they make a hell of their existence. It's not a pretty picture, these five miserable, unsuccessful people, but nevertheless it is the strongest part of this book. Especially the relation between the elderly parents Alfred and Enid is appallingly sketched (the couple reminded me of Archie and Edith in the US television series "all in the family", from the 70s, but that was comedy and satire, this is pure tragedy). Also the link Franzen makes with developments in American capitalism (predatory acquisitions that help people and businesses go to ruin, but make others - the handy ones - super rich) is interesting.

But there ends my praise, I fear. The five family members Franzen are desperately turning in circles, they do not get out of their obsessive correction-line, although the very cliché epilogue suggests some openings. This makes the story falter, and I even noticed some signs of boredom while reading the second part of the novel. And then there's this obsession of (mainly) American authors to demonstrate their writing skills, which results for example in overly scientific passages that really hinder the flow of the story. Franzen has something up his sleeve, that's clear, but with 'the Corrections' he has not yet convinced me.

To me this looks like the red line in this novel 'The Corrections' by Jonathan Franzen, though he also plays with other contexts in which the word “correction” is relevant (a correction on the stock exchange for example).

Franzen focuses on an average family in the Midwest of the United States, the Lamberts. The five members of this member are so obsessed by "correcting" their lives, that they make a hell of their existence. It's not a pretty picture, these five miserable, unsuccessful people, but nevertheless it is the strongest part of this book. Especially the relation between the elderly parents Alfred and Enid is appallingly sketched (the couple reminded me of Archie and Edith in the US television series "all in the family", from the 70s, but that was comedy and satire, this is pure tragedy). Also the link Franzen makes with developments in American capitalism (predatory acquisitions that help people and businesses go to ruin, but make others - the handy ones - super rich) is interesting.

But there ends my praise, I fear. The five family members Franzen are desperately turning in circles, they do not get out of their obsessive correction-line, although the very cliché epilogue suggests some openings. This makes the story falter, and I even noticed some signs of boredom while reading the second part of the novel. And then there's this obsession of (mainly) American authors to demonstrate their writing skills, which results for example in overly scientific passages that really hinder the flow of the story. Franzen has something up his sleeve, that's clear, but with 'the Corrections' he has not yet convinced me.

First things first. If you are the sort of reader who insists on finding some likeable quality in your protagonists, don't read this book. You will be bitterly disappointed by the entire cast of characters.

Second things second, why be that kind of reader? Sure, I want my friends-in-real-life to be likeable and worthy of respect. My friends-in-fiction can be complete jerks, as long as they're complex and well-written jerks.

And man, does Franzen write some excellent jerks. The entire Lambert clan is full of them, and they all have such specific and distinct voices. None of them are perfect, yet none of them are entirely villainous either. They are consistently and richly themselves in all ways: in their words, actions, self-justifications, and general obliviousness.

Franzen and [a:Lionel Shriver|45922|Lionel Shriver|http://photo.goodreads.com/authors/1270519768p2/45922.jpg] are two of my favorite writers because they have this talent in common -- to show me a character rather than simply tell me about them. And in the middle of all that show-not-tell-ingness, Franzen intersperses word-gems like these:

C'mon now, wasn't that worth reading?

One more thing... I have a theory about [b:The Corrections|3805|The Corrections|Jonathan Franzen|http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/5102ZF98GDL._SL75_.jpg|941200] versus [b:Freedom|7905092|Freedom|Jonathan Franzen|http://photo.goodreads.com/books/1316729686s/7905092.jpg|9585796]: Jonathan Franzen has a limited bag of tricks. I love these tricks, but after reading one book, you become familiar with the tricks and they lose their appeal. So of those two books, you'll prefer whichever one you read first. For those of you who read both, please let me know whether my theory is valid, or full of crap.

Second things second, why be that kind of reader? Sure, I want my friends-in-real-life to be likeable and worthy of respect. My friends-in-fiction can be complete jerks, as long as they're complex and well-written jerks.

And man, does Franzen write some excellent jerks. The entire Lambert clan is full of them, and they all have such specific and distinct voices. None of them are perfect, yet none of them are entirely villainous either. They are consistently and richly themselves in all ways: in their words, actions, self-justifications, and general obliviousness.

Franzen and [a:Lionel Shriver|45922|Lionel Shriver|http://photo.goodreads.com/authors/1270519768p2/45922.jpg] are two of my favorite writers because they have this talent in common -- to show me a character rather than simply tell me about them. And in the middle of all that show-not-tell-ingness, Franzen intersperses word-gems like these:

And when the event, the big change in your life, is simply an insight -- isn't that a strange thing? That absolutely nothing changes except that you see things differently and you're less fearful and less anxious and generally stronger as a result: isn't it amazing that a completely invisible thing in your head can feel realer than anything you've experienced before? You see things more clearly and you know that you're seeing them more clearly. And it comes to you that this is what it means to love life, this is all anybody who talks seriously about God is ever talking about. Moments like this.

C'mon now, wasn't that worth reading?

One more thing... I have a theory about [b:The Corrections|3805|The Corrections|Jonathan Franzen|http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/5102ZF98GDL._SL75_.jpg|941200] versus [b:Freedom|7905092|Freedom|Jonathan Franzen|http://photo.goodreads.com/books/1316729686s/7905092.jpg|9585796]: Jonathan Franzen has a limited bag of tricks. I love these tricks, but after reading one book, you become familiar with the tricks and they lose their appeal. So of those two books, you'll prefer whichever one you read first. For those of you who read both, please let me know whether my theory is valid, or full of crap.

This book is a crime against humanity.

No one should have to go through 700 pages of life's griefs described so accurately as to be no longer narrative, no longer fiction, no longer interesting, just the dreaded misunderstandings of daily life that accumulate to a lifelong of unhappiness, lost relationships, guilt, disappointed expectations, resentments petty and otherwise.

I get the author's brilliance of bringing the reader at the end to sympathize with all the characters who are at the start and who continue to be judgmental, narrow-minded, selfish, and highly unlikable. At the end you see that the son feels misjudgged, the daughter feels confined, the other son feels rejected, the father feels misunderstood, and the mother is terrified of loneliness.

How that justifies the fact that none of them ever really find peace, none of the issues find resolution, how the only development is that they are forced to face a reality that one of them hasn't been facing. Hooray. Big development. After 700 pages.

The only issue treated in this book that is common but not intrinsic to the human condition is dementia. And to exploit the horror of it to flesh out the faults of the characters, to repeatedly harp on the humiliation and the erosion of the afflicted, the unwavering denial and cruelty of the spouse, and the children's preoccupation with their own frustrations - whatever the justification - why write about it so realistically that it has none of the occasional reprieves that even life gives us?

No one should have to go through 700 pages of life's griefs described so accurately as to be no longer narrative, no longer fiction, no longer interesting, just the dreaded misunderstandings of daily life that accumulate to a lifelong of unhappiness, lost relationships, guilt, disappointed expectations, resentments petty and otherwise.

I get the author's brilliance of bringing the reader at the end to sympathize with all the characters who are at the start and who continue to be judgmental, narrow-minded, selfish, and highly unlikable. At the end you see that the son feels misjudgged, the daughter feels confined, the other son feels rejected, the father feels misunderstood, and the mother is terrified of loneliness.

How that justifies the fact that none of them ever really find peace, none of the issues find resolution, how the only development is that they are forced to face a reality that one of them hasn't been facing. Hooray. Big development. After 700 pages.

The only issue treated in this book that is common but not intrinsic to the human condition is dementia. And to exploit the horror of it to flesh out the faults of the characters, to repeatedly harp on the humiliation and the erosion of the afflicted, the unwavering denial and cruelty of the spouse, and the children's preoccupation with their own frustrations - whatever the justification - why write about it so realistically that it has none of the occasional reprieves that even life gives us?

Franzen does a great job of making you care and root for deeply flawed characters.

Franzen is just an amazing writer, and I know that because he took me from laughter to tears several times, sometimes in a single page.

In the end, I wasn't really 100% sure how to feel about the characters in The Corrections, they all have a few redeeming qualities and a hundred horrible ones, but in the end, they're all just people. Imperfect people trying to get through life, and Franzen captures this beautifully.

In the end, I wasn't really 100% sure how to feel about the characters in The Corrections, they all have a few redeeming qualities and a hundred horrible ones, but in the end, they're all just people. Imperfect people trying to get through life, and Franzen captures this beautifully.

Depressing, depressed characters who think everyone in their family is plotting against them, when really everyone is just too into themselves. I don't know why people love this book; I just thought i was ok.

One of those yawning time capsule books that belongs only in the year in which it was written. Cool words here and there!