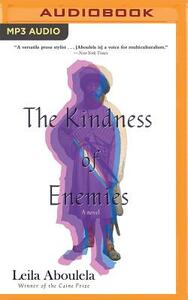

Take a photo of a barcode or cover

at first, I find it hard to think about the connection between Natasha’s story and Imam Shamil’s, other than the fact that she was doing a research about his life and legacies. In the end, I understand the connection, and it was such a beautiful story... The historical story making me doing my own research on Imam Shamil, and the fictional story was so entertaining and heartwarming to read...

Enjoyed this book quite a bit, and learned some history I knew nothing about: 19th century Muslim resistance to Russian occupation of the Caucasus. The story is intertwined with the story of a modern-day Russian-Sudanese academic who studies Shamil while angsting about her complicated identity as Muslim and not Muslim, African and not African. I found her story interesting too, but it got less air time than the other and it felt like some depth was missing. Maybe would have preferred to read these two stories separately.

There are two stories in this book. One is a fictionalized story of an historical event, set in mid-nineteenth century Dagestan, where Islamic rebels led by Imam Shamil, are fighting for independence from Roman Catholic Russia.

The other story, which is loosely connected to the first, is set in 2010 Scotland where Natasha (Hussein) Wilson, a university professor, is researching Imam Shamil. Her friend is Malak, a Muslim, who owns Shamil's prized samovar, passed down in her family.

With continuing strife in this part of the world, the historical chapters seem almost contemporary. The Russians and Georgians are enemies, distrustful of and merciless with each other. However the fictionalized account centers on the characters on both sides and, despite their differences, their relationships with each other.

I found the historical story most compelling, with only tenuous hooks into the contemporary story, parts of which are extraneous. Both stories are multicultural and deal with the tensions, political and personal, among those from different cultures.

The other story, which is loosely connected to the first, is set in 2010 Scotland where Natasha (Hussein) Wilson, a university professor, is researching Imam Shamil. Her friend is Malak, a Muslim, who owns Shamil's prized samovar, passed down in her family.

With continuing strife in this part of the world, the historical chapters seem almost contemporary. The Russians and Georgians are enemies, distrustful of and merciless with each other. However the fictionalized account centers on the characters on both sides and, despite their differences, their relationships with each other.

I found the historical story most compelling, with only tenuous hooks into the contemporary story, parts of which are extraneous. Both stories are multicultural and deal with the tensions, political and personal, among those from different cultures.

When will blood stop flowing on the mountains?

When the sugarcane grows in snow.

When the sugarcane grows in snow.

When news broke last week of attacks in Beirut, Paris, and other cities around the world, as I always do, I turned to fiction to help make sense of the ongoing tragedy. Of course there isn’t any real sense to be found in the violent deaths of innocents; there never is. But suddenly my reading of The Kindness of Enemies took on a new urgency. Now more than ever, understanding Islam feels like an imperative, and more importantly, marking the distinction between its earnest practitioners and its extremists. Reading fiction is a consistent way in for me to cultures and experiences outside my own. It strips away the foreignness I feel as I read journalistic reports and use as a convenient excuse for my ignorance. I may easily dismiss “that group” as other, but I can’t do the same with “that character.” The specificity of fiction, though it may not represent truth in the same way a news article would, points me toward the larger, more fundamental truths of real, complicated, global life.

Leila Aboulela’s novel shines a light on the events of last week, and in so doing reveals a need for nuance in our approach to questions of religion and extremism. Natasha, a professor at a university in Scotland, bonds with a student and his mother over a weekend spent snowed in at their home, but when the student comes under investigation for terrorist activity, she has to reevaluate their every interaction. Was he harboring fantasies of violent jihad? Were there signs that she ignored because she liked him, respected his intellect? How much responsibility should she bear, if the claims of the police prove true?

Natasha's situation is further complicated by her own ambivalence toward her heritage. Her father is Sudanese, her mother Russian, which leaves Natasha in between two cultures, not feeling as if she belongs anywhere. She claims Islam culturally, but is not a practicing Muslim; her almost compulsive tendency to distance herself from her father's religion echoes throughout her narration.

Aboulela includes chapters that flash back to the mid-1800s, telling the story of Imam Shamil, Natasha's prized student's ancestor and the focus of her own academic research. Shamil led a group of resistance fighters against the Russian army in the Caucasian War. These chapters portray compelling, sympathetic characters on both sides of the conflict—both Shamil and his family, and the families of his enemies—eloquently underscoring the point that, in war, identifying sides as “good” or “bad” is not always a simple proposition, much as we might try to make it so.

I still have a lot more questions than answers about what happened last week. But now that I've read Aboulela's book, I've at least learned some of the right questions to ask.

With regards to Grove Atlantic and NetGalley for the advance copy. On sale 5 January 2016.

More book recommendations by me at www.readingwithhippos.com

Leila Aboulela’s novel shines a light on the events of last week, and in so doing reveals a need for nuance in our approach to questions of religion and extremism. Natasha, a professor at a university in Scotland, bonds with a student and his mother over a weekend spent snowed in at their home, but when the student comes under investigation for terrorist activity, she has to reevaluate their every interaction. Was he harboring fantasies of violent jihad? Were there signs that she ignored because she liked him, respected his intellect? How much responsibility should she bear, if the claims of the police prove true?

Natasha's situation is further complicated by her own ambivalence toward her heritage. Her father is Sudanese, her mother Russian, which leaves Natasha in between two cultures, not feeling as if she belongs anywhere. She claims Islam culturally, but is not a practicing Muslim; her almost compulsive tendency to distance herself from her father's religion echoes throughout her narration.

Aboulela includes chapters that flash back to the mid-1800s, telling the story of Imam Shamil, Natasha's prized student's ancestor and the focus of her own academic research. Shamil led a group of resistance fighters against the Russian army in the Caucasian War. These chapters portray compelling, sympathetic characters on both sides of the conflict—both Shamil and his family, and the families of his enemies—eloquently underscoring the point that, in war, identifying sides as “good” or “bad” is not always a simple proposition, much as we might try to make it so.

I still have a lot more questions than answers about what happened last week. But now that I've read Aboulela's book, I've at least learned some of the right questions to ask.

With regards to Grove Atlantic and NetGalley for the advance copy. On sale 5 January 2016.

More book recommendations by me at www.readingwithhippos.com

I can't say I really liked Natasha, but I don't think she's supposed to be a likeable character necessarily. Once I got over wanting to like her personally, I really enjoyed both the 1800s chapters and the modern chapters.

this was interesting not for me but interesting. the one thing i didnt get is the connection between the two timelines. the connection was not strong enough so when we were going back and forth it was jaring.

challenging

emotional

informative

reflective

sad

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

A mix

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Yes

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Complicated

I love that the book does not pass judgment on any of the characters and does not push 21st-century morals on historical figures.

Confusing, but entertaining

Only toward the end of the book did I begin to see the parallels which I assume the author was drawing. Which is to say that they were not terribly vibrant to begin with. The story of Natasha leaves a lot to be desired up til the end. The story of Imam Shamil and his sons is much more valuable in terms of storytelling, while the story of Anna is incidental and not terribly germane to the novel, in my opinion. Probably more of a 2.5 stars book, but I’m interested in the region and the life of Shamil now, so any book that piques interest is valuable.

Only toward the end of the book did I begin to see the parallels which I assume the author was drawing. Which is to say that they were not terribly vibrant to begin with. The story of Natasha leaves a lot to be desired up til the end. The story of Imam Shamil and his sons is much more valuable in terms of storytelling, while the story of Anna is incidental and not terribly germane to the novel, in my opinion. Probably more of a 2.5 stars book, but I’m interested in the region and the life of Shamil now, so any book that piques interest is valuable.

Compelling and interesting story. I knew nothing of the background/setting, so I can’t speak to its accuracy but I enjoyed the blend of storytelling and history. The major characters were frustratingly selfish and irritatingly arrogant.