Take a photo of a barcode or cover

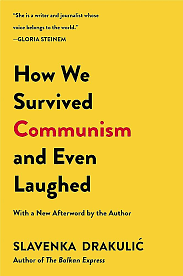

This is a collection of essays drawing lessons from the lives of women who lived through communism. While the individual essays provide a unique perspective and are thought-provoking, they do not compliment each other to form a coherent collection.

“Democracy is not like an unexpected gift that comes without effort. It must be fought for. And that is what makes it so difficult.”

I started reading this book almost on a whim. I first heard about it through Goodreads and seeing an update about it, but I just put it on my to-read list and went my merry way. A few days ago, I saw it on my e-reader and decided to just read through a bit of the first few chapters. I’m not sure how much my consciousness was attuned to current events at that point, as it just started getting crazy, but this has certainly been an appropriate read this week.

Slavenka Drakulić is an underrated journalist and writer who in this book gives the reader an extremely intimate and personal view of post-Communist Yugoslavia in the early 1990s. At that stage, communism was gone, but the specter still lay over the people… and of course civil war was on the horizon. Drakulić doesn’t get too caught up in politics or wars, though, because her purview here is much more interesting: the daily life of people, particularly women.

“The reality is that communism persists in the way people behave, in the looks on their faces, in the way they think. Despite the free elections and the celebration of new democratic governments taking over in Prague, Budapest, and Bucharest, the truth is that the people still go home to small, crowded apartments, drive unreliable cars, worry about their sickly children, do boring jobs — if they are not unemployed — and eat poor quality food. Life has the same wearying immobility; it is something to be endured, not enjoyed.”

The chapters deal with different topics, whether it is an old doll, doing the laundry, or engaging with ignorant (no matter how well-meaning) westerners. The anecdote about the American scholar asking about what the Yugoslavian feminists were thinking or doing about a particular thing was pretty humorous; I think they’ve got bigger things on their plates than critical theory. One thing that pervades the book is the poverty and scarcity that is like a scar of communism—no matter where you look, the attitudes and living situations and all else are shaped by this scarcity.

“There may be neither milk nor water, but there is sure to be a bottle of Coke around. Nobody seems to mind the paradox that even though fruit grows throughout Poland, there is no fruit juice yet Coke is everywhere. But here Coke, like everything coming from America, is more of a symbol than a beverage.”

This book was definitely an eye-opener for me. I’ve never lived in a post-Communist country, and certainly didn’t spare particular attention on the lives of women in these areas. The author visits and tells the story of different women that she encounters, and though they are all ‘ordinary’, their stories are nevertheless fascinating and reach out to a shared sense of humanity. Though the events we see through the author’s eyes, from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the Velvet Revolution and the first free elections in Yugoslavia, are still in living memory for many, it is harder and harder to justify the significance of memorizing and recalling these events, especially for my generation (who was born afterwards). Right now the world is in crisis mode, and nobody feels it more strongly than people in post-Communist countries.

I don’t want to discuss the book too much because it’s a captivating read, with Drakulić’s style being quite readable but also elegant. There were a few moments towards the end where she tends to wax on a bit more abstractly, but that may just have been my inability to focus on things at the moment. Overall, this book was an important one to read, and I will be adding Drakulić’s other works to my list. But you really should just go ahead and read this yourself, since it’s a fairly ‘quick’ read (but it’s well worth letting the words settle in your mind and go through it a bit slowly, because it definitely hits hard). In a modern world where we see suburban upper-class teens and young adults idolize communism and see nothing wrong with the actions of the former Soviet Union/modern Russia, Drakulić’s work is more important than ever so that we do not forget the true effects of communism.

A few of my favorite quotes:

“This is it, I thought, the erasing of memory begins right here, right on this spot near the Potsdamer Platz, right when Goering is reduced to a very famous person , and the Wall to tiny bits of painted concrete selling for 5 Deutschmarks, when the whole history of this nation is reduced to souvenirs and fame.”

“I sprinkled Eastern Europe with tampons on my travels…”

“It took me time to see that any kind of ideology could reduce us to poverty and emotional suffering.”

“It was only in the late seventies that toilet rolls became a normal thing, together with regular washing of hands, brushing of teeth, and bathing - but not using a deodorant. In other words, our hygienic habits slowly but surely changed for the better, and one didn’t die immediately upon entering a crowded streetcar - only a little later.”

“For myself, I concluded, it’s easier to give than not to give. It’s easier to believe them. Then I don’t have to fight my conscience, prove to myself that I don’t need to give, which seems to be as hard as to make sure you gave money to the ‘right’ person - because there are no ‘right’ people.”

“The ‘iron curtains’ will stay with us for a long time: in our memories, in our lives that we cannot renounce, no matter how difficult they were and how hard we try.”

“Talking to them always makes me feel like the worst kind of dissident, a right-wing freak (or a Republican, at best), even if I consider myself an honest social democrat. For every mild criticism of life in the system I have been living under for the last forty years they look at me suspiciously, as if I were a CIA agent (while my folks, communists back home, never had any doubts about it — perhaps this is the key difference between Eastern and Western comrades?) But one can hardly blame them. It is not the knowledge about communism that they lack — I am quite sure they know all about it — it’s the experience of living under such conditions.”

“‘You’d be surprised, my dear, to know that people have to live and survive during wars, too. Besides, how do you think we survived communism?’”

якось — дуже недавно — ми сиділи за вином із двома друзями, жінкою мого віку й на півтора десятка років старшим чоловіком, говорили про дорослішання (його — пізньорадянське, наше — пострадянське, не сильно інше) й зачепили тему прокладок. тобто браку прокладок — і того відчуття, коли надворі пізні дев'яності, уже не вкрай кризові, але все одно, а ти стаєш підлітком, і до фізіологічних змін додається чимале погіршення якості життя у вигляді ганчірочок, які перекручуються, збиваються в грудки й вимагають якнайконспіративнішого ручного прання. на наші вже смішні, проте цілковито трагічні, коли тобі дванадцять, історії друг відреагував здивовано: «стоп, але ж у пізніх дев'яностих прокладки вже скрізь були».

він зрозумів, що впоров дурницю, щойно ми подякували йому за менсплейнінг (і київсплейнінг) наших безпосередніх досвідів. зате це стало приводом налити ще вина й поговорити про відмінності між життям у провінції й у столиці.

славенка дракуліч пише про комунізм на балканах — але з тим самим успіхом вона могла би писати про перше пострадянське десятиліття на волині (чи, підозрюю, в будь-якому не центрі). воно все там: від тітчиних баночок із лаком для нігтів, сто разів розведеним ацетоном, і залишків помади, які треба виколупувати з тюбика пальцем, до миття посуду в холодній воді і з пральним порошком (чи полоскання постелі в крижаній — не тому, що так за технологією, а тому, що пощастило й була можливість поставити балію біля криниці, щоб не таскати відра, — воді з синькою і крохмалем); від книжкових сторінок замість туалетного паперу (чи не тому, що я ще змалку звикла до історій без початку й кінця, мене не вразив усілякий постмодернізм?) до п'яти людей, що живуть у кімнаті три на три метри, й загалом одинадцяти на трикімнатну хату; від німецького катологу «товари поштою» — найкрасивішої речі вдома й нескінченного джерела натхнення в іграх — до прання поліетиленових пакетиків; від централізованого вимикання світла на дві години щовечора до шкільного гуртожитка, де ключ від підвальних душів вашій кімнаті видають раз на тиждень, а решту часу можете користуватися загальними умивальниками й ногомийниками, встановленими в одному великому приміщенні. одне слово, про гідність, умов для збереження якої у вас особливо не знаходиться.

тут, на гудрідсі, є коментарі від молодих чоловіків, які звинувачують славенку дракуліч у сексизмі, дріб'язковості й відбиванні в них бажання одружуватися: мовляв, косметики їм не робили, от же ж трагедія, альо, не було часу на косметику за відбудовою держави. що доволі кумедно, бо сама дракуліч цей аргумент згадує і трохи з нього підсміюється — ну, знаєте, тим сміхом, що й загалом із комунізму. а ще вона прямим текстом пише, що прокладки (як, зрештою, і косметика, як і туалетний папір, як і пральна машина) — це взагалі-то метафора; хоча, треба визнати, не тільки метафора, бо дискомфорт від браку цього всього цілковито намацальний. і я аж не знаю, тішитися з того, що є більш-менш мої однолітки, які have no idea what she's talking about, чи все-таки тривожитися, що є більш-менш мої однолітки, яким навіть прямим текстом складно пояснити про зв'язок побуту з гідністю і про те, чому жіночі досвіди тут відрізняються від чоловічих, але все одно заслуговують на проговорення.

він зрозумів, що впоров дурницю, щойно ми подякували йому за менсплейнінг (і київсплейнінг) наших безпосередніх досвідів. зате це стало приводом налити ще вина й поговорити про відмінності між життям у провінції й у столиці.

славенка дракуліч пише про комунізм на балканах — але з тим самим успіхом вона могла би писати про перше пострадянське десятиліття на волині (чи, підозрюю, в будь-якому не центрі). воно все там: від тітчиних баночок із лаком для нігтів, сто разів розведеним ацетоном, і залишків помади, які треба виколупувати з тюбика пальцем, до миття посуду в холодній воді і з пральним порошком (чи полоскання постелі в крижаній — не тому, що так за технологією, а тому, що пощастило й була можливість поставити балію біля криниці, щоб не таскати відра, — воді з синькою і крохмалем); від книжкових сторінок замість туалетного паперу (чи не тому, що я ще змалку звикла до історій без початку й кінця, мене не вразив усілякий постмодернізм?) до п'яти людей, що живуть у кімнаті три на три метри, й загалом одинадцяти на трикімнатну хату; від німецького катологу «товари поштою» — найкрасивішої речі вдома й нескінченного джерела натхнення в іграх — до прання поліетиленових пакетиків; від централізованого вимикання світла на дві години щовечора до шкільного гуртожитка, де ключ від підвальних душів вашій кімнаті видають раз на тиждень, а решту часу можете користуватися загальними умивальниками й ногомийниками, встановленими в одному великому приміщенні. одне слово, про гідність, умов для збереження якої у вас особливо не знаходиться.

тут, на гудрідсі, є коментарі від молодих чоловіків, які звинувачують славенку дракуліч у сексизмі, дріб'язковості й відбиванні в них бажання одружуватися: мовляв, косметики їм не робили, от же ж трагедія, альо, не було часу на косметику за відбудовою держави. що доволі кумедно, бо сама дракуліч цей аргумент згадує і трохи з нього підсміюється — ну, знаєте, тим сміхом, що й загалом із комунізму. а ще вона прямим текстом пише, що прокладки (як, зрештою, і косметика, як і туалетний папір, як і пральна машина) — це взагалі-то метафора; хоча, треба визнати, не тільки метафора, бо дискомфорт від браку цього всього цілковито намацальний. і я аж не знаю, тішитися з того, що є більш-менш мої однолітки, які have no idea what she's talking about, чи все-таки тривожитися, що є більш-менш мої однолітки, яким навіть прямим текстом складно пояснити про зв'язок побуту з гідністю і про те, чому жіночі досвіди тут відрізняються від чоловічих, але все одно заслуговують на проговорення.

شاید کتاب های بسیاری در رابطه با کمونیسم وجود داشته باشد. درباره ی ایدئولوژی ها و چیزهای بزرگ آن. اما فکر می کنم کمتر کسی به جزئیات آن توجه کرده باشد. به تاثیرات کوچک و بزرگی که بر زندگی مردم می گذارد. از نحوه ی زندگی و فکر کردنشان تا غذا، لوازم بهداشتی، پوشاک، یا...

و این کتاب دقیقا همان جزئیات کوچک و ریزی بود که گفته نشده بودند. که من دلم می خواست بدانمشان. و فکر می کنم که همه مان می توانیم با پوست و گوشتمان درکش کنیم. لمسش کنیم.

غم و غصه خیلی درش موج می زد و من رو چندین بار به گریه انداخت. شاید نه خود نثر کتاب بلکه چیزی فراتر از اون. چیزی که شاید خود ما هم تجربه اش کرده ایم. آن ارتباطی که با زندگی ما می تواند به خوبی بر قرار کند.

و لازم می دونم به ترجمه خیلی خوب و روانش هم اشاره کنم که به نحوی بود که فکر نمی کردی کتاب ترجمه شده است!

پ.ن: مرا به خواندن بقیه ی مجموعه "تجربه و هنر زندگی" ترغیب کرد.

پ.ن دو: توی دانشگاه برای دوستانم فصل هایی را بلند خوانده ام که این اتفاق و آن احساسی که از شنیدن جمعی اش، از کنار هم نشستن و بلند کتاب خواندن، در من ایجاد شد، این کتاب را در ذهنم ماندگار تر کرد. :)

و این کتاب دقیقا همان جزئیات کوچک و ریزی بود که گفته نشده بودند. که من دلم می خواست بدانمشان. و فکر می کنم که همه مان می توانیم با پوست و گوشتمان درکش کنیم. لمسش کنیم.

غم و غصه خیلی درش موج می زد و من رو چندین بار به گریه انداخت. شاید نه خود نثر کتاب بلکه چیزی فراتر از اون. چیزی که شاید خود ما هم تجربه اش کرده ایم. آن ارتباطی که با زندگی ما می تواند به خوبی بر قرار کند.

و لازم می دونم به ترجمه خیلی خوب و روانش هم اشاره کنم که به نحوی بود که فکر نمی کردی کتاب ترجمه شده است!

پ.ن: مرا به خواندن بقیه ی مجموعه "تجربه و هنر زندگی" ترغیب کرد.

پ.ن دو: توی دانشگاه برای دوستانم فصل هایی را بلند خوانده ام که این اتفاق و آن احساسی که از شنیدن جمعی اش، از کنار هم نشستن و بلند کتاب خواندن، در من ایجاد شد، این کتاب را در ذهنم ماندگار تر کرد. :)

A rambly look at the mundane details of life under communism. It was interesting to hear about daily hardships that were the accepted facts of life, but I grew a little weary with the author's forays into philosophizing about politics and communism in general. I know what communism is about; I just wanted to hear the other side of the coin, the hidden details that we Westerners wouldn't have thought about. On a more positive note, it did make me want to read more about the history of communism in Eastern Europe, since my education was very light on the social studies and I knew very little about the events of which the author spoke.

Another book for a class, this is the second time I've read this one. I honestly love reading this book because of the amount of different perspectives that are brought into it. You get something new out of it each time and its such a personalized take on the things that she went through

An absolutely cherished book that really started me down the path of academia. Teaching it to my students feels genuinely thrilling.

I can't even begin to express my deep gratitude for the words and stories told in this book. Women in communist Europe share their seemingly ordinary lives under this oppressive regime. Drakulic beautifully weaves these stories into a singular narrative: women can, and will, have a voice.

Curious about the impact of this time on modern femininity and hope to find more translated texts.

Having traveled widely in communist countries and spoken to many women, Drakulic has assembled a sort of collage of sketches of how they got by, from eating to clothes washing or finding toys. Her eye is critical, having lived herself under a regime that took many freedoms, sometimes to the point of humiliation. I read it with great interest, quickly, on the road, and can recommend it to anyone curious of such things, with the caution - immerse in the stories, but keep in mind how political they really are.

<< “This is our food” says Evelina “we are used to swallowing politics with out meals. For breakfast you eat elections, a parliament discussion comes for lunch, and at dinner you laugh at the evening news or get mad at the lies that the Communist Party is trying to sell, in spite of everything”. Perhaps these people can live almost without food - either because it’s too expensive or because there is nothing to buy, or both - without books and information, but not without politics. >>

<< In this silent war, the losers are our cities. Entranceways into buildings not only serve for entry but double as toilets, as well as places to express your deep inner feelings.These feelings (if you can manage to ignore the smell) are hatred and destruction. >>

<< “This is our food” says Evelina “we are used to swallowing politics with out meals. For breakfast you eat elections, a parliament discussion comes for lunch, and at dinner you laugh at the evening news or get mad at the lies that the Communist Party is trying to sell, in spite of everything”. Perhaps these people can live almost without food - either because it’s too expensive or because there is nothing to buy, or both - without books and information, but not without politics. >>

<< In this silent war, the losers are our cities. Entranceways into buildings not only serve for entry but double as toilets, as well as places to express your deep inner feelings.These feelings (if you can manage to ignore the smell) are hatred and destruction. >>