Take a photo of a barcode or cover

informative

reflective

fast-paced

What is it that a woman requires? According to Virginia Woolf, it’s a room of her own and five hundred a year. While the room might seem like a physical space, it is also metaphorically a space in which she can voice her opinions. The essay follows a linear structure, beginning with meals at two different Oxbridge colleges, which essentially shape the narrator’s thought process. The differing experiences gleaned from these two meals highlight outbursts of class and gender disparity. Amenities were never afforded to women, as they could only focus on the essentials in a women’s college due to economic disparity.

Her body wanders along with the reader’s mind as she moves through places like the British Museum. She discusses literature, pointing out how, in earlier times, men freely wrote about women—even though no formal education was required for them to comment on women’s lives—while women’s own writings were sparse. Woolf’s radical approach has propelled A Room of One’s Own to become one of the founding texts of feminist criticism. However, it lacks the key aspects that later waves of feminism, especially the third wave, have struggled to bring to the forefront: intersectionality and embracing collectivity.

Her words—“But, nevertheless, she had certain advantages which women of far greater gift lacked even half a century ago. Men were no longer to her ‘the opposing faction’; she need not waste her time railing against them; she need not climb onto the roof and ruin her peace of mind longing for travel, experience and a knowledge of the world and character that were denied her”—exemplify how she celebrates the moment when women no longer feel that men are “the opposing faction.” Yet, as a woman—especially, a woman of colour—in the 21st century, where news articles are still filled with threats of domestic violence, femicide, transphobia, and acid attacks over the simplest matters, Woolf’s dissuasion of rallying against men feels both privileged and complicit in a world still plagued by the effects of patriarchy.

When she grows angry at a professor for wrongly disparaging a woman’s voice in the British Museum, that anger remains central to her critique of women’s limitations. Yet, contrastingly, her urge to condescendingly discipline women for their approach to feminism feels white-washed. Claiming feminism’s fight is over—when only a fraction of women worldwide have achieved basic equality—is a mischaracterisation of what feminism truly stands for.

Despite my differences with Woolf’s feminist theory—often fueled by differences in race and era—she undeniably created rooms and spaces for women. Her essays and novels opened doors for many. In A Room of One’s Own, Woolf doesn’t just talk about women and literature—she questions the entire way we think about women in history and scholarship. Instead of relying on cold, logical arguments, she uses imagination and storytelling to fill in the silences history has left about women. She believes that true art should burn away the personal and reflect something more intense and universal—a kind of emotional clarity she calls "incandescence." Her essay becomes a kind of performance, not just arguing for women’s voices in literature, but showing what that voice can look like when it’s free, creative, and fiercely intelligent.

Her body wanders along with the reader’s mind as she moves through places like the British Museum. She discusses literature, pointing out how, in earlier times, men freely wrote about women—even though no formal education was required for them to comment on women’s lives—while women’s own writings were sparse. Woolf’s radical approach has propelled A Room of One’s Own to become one of the founding texts of feminist criticism. However, it lacks the key aspects that later waves of feminism, especially the third wave, have struggled to bring to the forefront: intersectionality and embracing collectivity.

Her words—“But, nevertheless, she had certain advantages which women of far greater gift lacked even half a century ago. Men were no longer to her ‘the opposing faction’; she need not waste her time railing against them; she need not climb onto the roof and ruin her peace of mind longing for travel, experience and a knowledge of the world and character that were denied her”—exemplify how she celebrates the moment when women no longer feel that men are “the opposing faction.” Yet, as a woman—especially, a woman of colour—in the 21st century, where news articles are still filled with threats of domestic violence, femicide, transphobia, and acid attacks over the simplest matters, Woolf’s dissuasion of rallying against men feels both privileged and complicit in a world still plagued by the effects of patriarchy.

When she grows angry at a professor for wrongly disparaging a woman’s voice in the British Museum, that anger remains central to her critique of women’s limitations. Yet, contrastingly, her urge to condescendingly discipline women for their approach to feminism feels white-washed. Claiming feminism’s fight is over—when only a fraction of women worldwide have achieved basic equality—is a mischaracterisation of what feminism truly stands for.

Despite my differences with Woolf’s feminist theory—often fueled by differences in race and era—she undeniably created rooms and spaces for women. Her essays and novels opened doors for many. In A Room of One’s Own, Woolf doesn’t just talk about women and literature—she questions the entire way we think about women in history and scholarship. Instead of relying on cold, logical arguments, she uses imagination and storytelling to fill in the silences history has left about women. She believes that true art should burn away the personal and reflect something more intense and universal—a kind of emotional clarity she calls "incandescence." Her essay becomes a kind of performance, not just arguing for women’s voices in literature, but showing what that voice can look like when it’s free, creative, and fiercely intelligent.

I had previously read excerpts from this novel for a class in university, which had me interested in reading the full text, but I found myself enjoying it much more than I even expected. The class had taken more of an interest in the more theoretical parts of the text, so that we could dissect her arguments, but I wasn’t expecting so much humor and narrative elements.

While I think separating the two makes it easier to digest what she is trying to get across, you are missing so much of her personality and perspective engaging with the text in this way. It’s like what Virginia was saying about the histories of female authors past being all but nonexistent. Some of their works survive them, but nothing of their circumstance, the building blocks for their work, so getting to know Virginia through this is very enjoyable.

The love that she has for writing, and writers, is palpable. She is a student of the craft in every sense, and even when she is analyzing something that she recognizes as not being as good as it could be, she is finding so many positives to highlight, and ways to justify and explain their work, in the absence of their own stories. This whole idea gets talked about in depth in an essay I read by Alice Walker, from her book ‘In Search of Our Mothers Gardens’. A pseudo speculative and somewhat somber work wondering what kind of artists our mothers would be, though the way they lived was also an art in itself. I may need to reread the book, because I think it’s possible given the time frame that this book was referenced there.

On the topic of having a room of one’s own, Virginia is clearly right and we can see this with the explosion of fantastic female writers in the 20th and 21st centuries. Not only having the tools and the time to write is not always enough. Men have long been afforded the option to live in a way that is conducive to nothing but enriching their minds. They don’t need to hope that a rich aunt feels an namesake bond, allowing them to pursue (in secret) a career in writing. They don’t need to steal a glance at the books that their brother or father have brought home from the library at the mens only college. To have a room of ones own is not only a luxury, but a basic right that was not being afforded to women in the time that Virginia is writing this, and in some places still is not.

On many topics in this book in relation to relationships, sexuality, gender (though she doesn’t have the modern language we would use today) Virginia is truly ahead of her time. Virginia Woolf, you would have truly loved multiple hour long video essays on youtube.

While I think separating the two makes it easier to digest what she is trying to get across, you are missing so much of her personality and perspective engaging with the text in this way. It’s like what Virginia was saying about the histories of female authors past being all but nonexistent. Some of their works survive them, but nothing of their circumstance, the building blocks for their work, so getting to know Virginia through this is very enjoyable.

The love that she has for writing, and writers, is palpable. She is a student of the craft in every sense, and even when she is analyzing something that she recognizes as not being as good as it could be, she is finding so many positives to highlight, and ways to justify and explain their work, in the absence of their own stories. This whole idea gets talked about in depth in an essay I read by Alice Walker, from her book ‘In Search of Our Mothers Gardens’. A pseudo speculative and somewhat somber work wondering what kind of artists our mothers would be, though the way they lived was also an art in itself. I may need to reread the book, because I think it’s possible given the time frame that this book was referenced there.

On the topic of having a room of one’s own, Virginia is clearly right and we can see this with the explosion of fantastic female writers in the 20th and 21st centuries. Not only having the tools and the time to write is not always enough. Men have long been afforded the option to live in a way that is conducive to nothing but enriching their minds. They don’t need to hope that a rich aunt feels an namesake bond, allowing them to pursue (in secret) a career in writing. They don’t need to steal a glance at the books that their brother or father have brought home from the library at the mens only college. To have a room of ones own is not only a luxury, but a basic right that was not being afforded to women in the time that Virginia is writing this, and in some places still is not.

On many topics in this book in relation to relationships, sexuality, gender (though she doesn’t have the modern language we would use today) Virginia is truly ahead of her time. Virginia Woolf, you would have truly loved multiple hour long video essays on youtube.

.

من هنوز از ویرجینا وولف کتاب دیگه ای نخوندم، اما داستان خودش رو بارها شنیدم.

انتظار این واقع بینی رو ازش نداشتم.

واقع بینی ای که حتی وقتی مخالف شیوه نگاه کردنش بودم نمیشه انکار کرد داشت به واقعیت نگاه میکرد. چیزی که بوده، هست و خواهد بود.

و این نگاه به واقعیت شایسته تحسینه از هر کس و در هر زمان.

لینک طاقچه

من هنوز از ویرجینا وولف کتاب دیگه ای نخوندم، اما داستان خودش رو بارها شنیدم.

انتظار این واقع بینی رو ازش نداشتم.

واقع بینی ای که حتی وقتی مخالف شیوه نگاه کردنش بودم نمیشه انکار کرد داشت به واقعیت نگاه میکرد. چیزی که بوده، هست و خواهد بود.

و این نگاه به واقعیت شایسته تحسینه از هر کس و در هر زمان.

لینک طاقچه

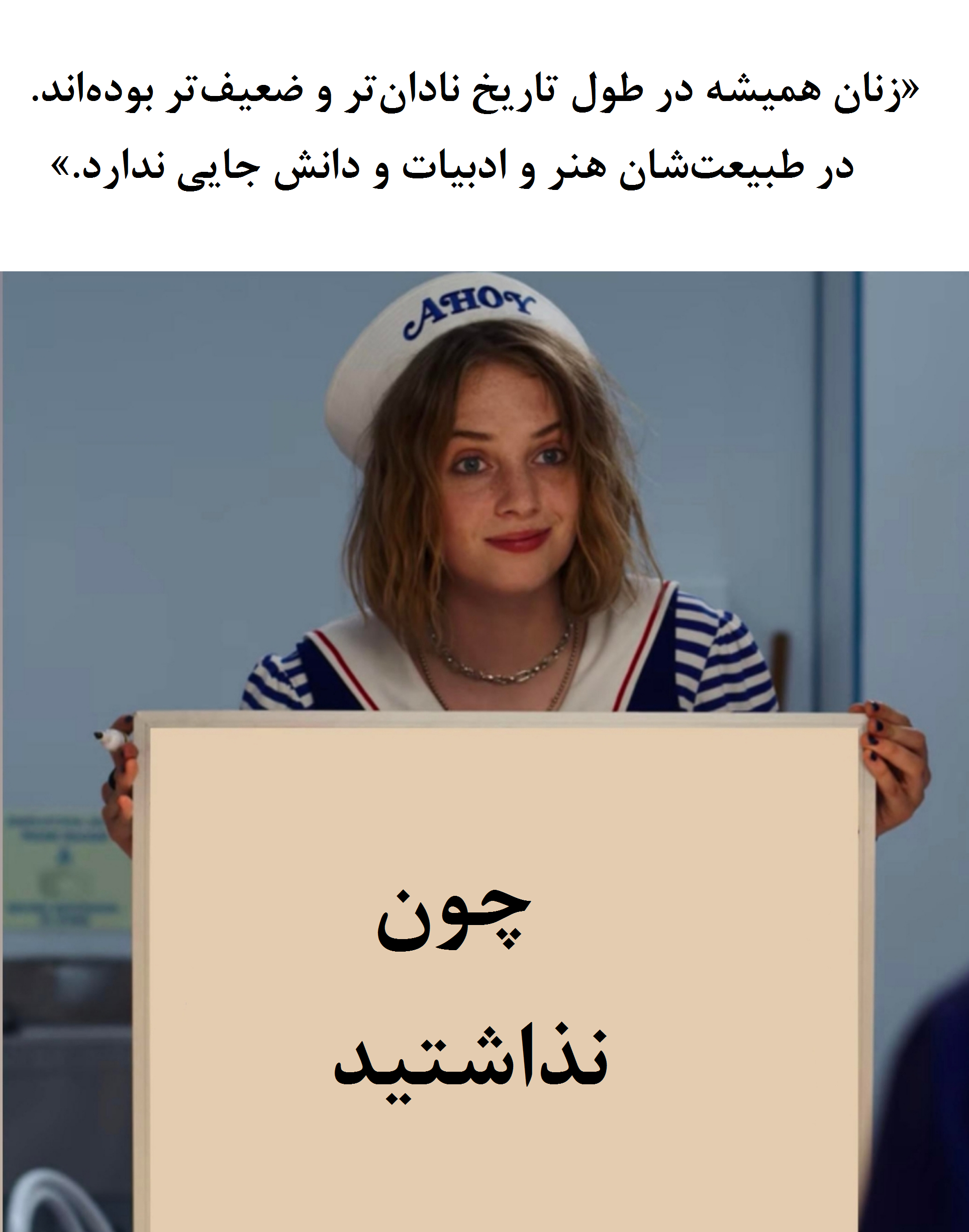

آشکار است که ارزشهای زنان اغلب با ارزشهایی که به دست جنسیت دیگر وضع شده، متفاوت است؛ طبیعتا چنین است. با این حال این ارزشهای مردانه است که غالب میشود؛ مثال پیشپاافتادهاش این است که فوتبال و ورزش مهم هستند و مُدپرستی و خرید لباس، بیارزش. و این ارزشها ناگزیر از زندگی به داستان منتقل میشوند. منتقدان میپندارند فلان کتاب مهم است، چون دربارهی جنگ است و بهمان کتاب بیاهمیت است، زیرا به احساسات زنان در اتاق نشیمن میپردازد.

نخستین باری که با «اتاقی از آن خود» آشنا شدم، متوجه نبودم کتاب قراره چی باشه. چند صفحه خوندم و نمیفهمیدم فیکشنه یا نانفیکشنه، راوی قراره کی باشه و آخرش میخواد داستان بگه یا مقاله بنویسه. کتاب رو رها کردم و چند روز پیش دوباره به سمتش برگشتم. سعی کردم دقت بیشتری روش داشته باشم. نثر رو بلعیدم و تازه فهمیدم خلاقیت متن همینجاست. صادقانه بگم هنوز هم خیلی چیزاش هستن که نمیفهمم و توی تحلیل چپترها هم نفهمیدم ولی دیگه فقط به عنوان ویژگی کتاب پذیرفتمشون. راوی هویت خودش رو نامعلوم باقی میذاره؛ گرچه مشخصه که گاهی نمیتونه از زبان کسی جز خود وولف باشه. اون به خواننده میگه که میتونید من رو مری بیتون، مری سیتون یا مری کارلایل بنامید و اهمیت نداره، و در ادامه همین نامها را جزء شخصیتهای کتاب میکنه. با مری سیتون گفتگو میکنه و نثر مری کارلایل رو تحلیل میکنه. راوی وولفه و مری بیتون و مری سیتون و مری کارلایل و هر زن دیگر، راویای جهانی. این ابهام به گونهای نقطه قوتشه.

به نظر میرسه وولف آزادی زنان رو از مردان انتظار نداره. در بخشی درباره حق تحصیل زنان مینویسه، و زحمت بسیاری که برای جمع کردن سی هزار پوند جمع شده که کفاف امکانات رفاهی تحصیل زنان رو هم نمیداده. وولف از مادران فقیر و مادران اونها اظهار خشم میکنه، زنانی که هیچ پولی نداشتند که برای تحصیل دخترانشون کنار بذارن.

«سخت برآشفتیم و فقر شرمآور جنسیت خود را تحقیر کردیم»

از مردان انتظاری نداره؛ مردانی که «پولشان را، مثل پدرها و پدربزرگهایشان، برای ایجاد کرسیهای استادی و تحقیق و جایزه و بورس جهت استفاده افراد جنسیت خود باقی میگذاشتند» و با این حال میدونه انتظار داشتن از مادران نسلهای پیشین احمقانهست «زیرا در وهله نخست، کسب درآمد برای آنها غیرممکن بود، و در وهله دوم، اگر هم ممکن بود، قانون آنها را از حق تملک پولی که به دست میآوردند محروم کرده بود».

وولف داستان غمانگیزی از این مینویسه که چی میشد اگه شکسپیر خواهری داشت که مثل اون به ادبیات علاقه داشت؟ اون نمیتونست آثار بزرگان ادبیات رو بخونه، تحصیل مناسبی داشته باشه و خانوادهش ازش میخواستن بهجای اینکه سرش توی کتاب باشه به مهارتهای زنانه و غذا و وصله برسه. شاید به زور و زود ازدواج کرده، شاید وقتی جلوی تماشاخانه ایستاد مسخرهش کردن، «چه کسی میتواند خشم و استیصال قلب شاعری را که در جسم زنی اسیر شده اندازه بگیرد؟» و سرانجام جون خودش رو گرفته. وولف این رو داستان زندگی احتمالیِ هر زن با ذوق ادبی در اون دوران میدونه، گرچه که فکر نمیکنه از اول پیشزمینهی ظهور و پرورش چنین ذوقی برای زنان اصلاً موجود نبوده که زنی بخواد ابراز علاقه به ادبیات بکنه. «زندگی آزاد در لندن قرن شانزدهم برای زنی شاعر و نمایشنامهنویس به معنای چنان فشار عصبی و معضلی بود که احتمال داشت او را از پا دربیاورد.» از این رو زنان به هویت موازی پناه میبردن و برای خودشون اسم مستعار مردانه انتخاب میکردن. «گمنامی در رگهای زنان جاری است».

«کلوئه الیویا را دوست داشت.»

وولف در بخشی از کتاب به هویت شخصیتهای زن در کتابها میپردازه. «به نظرم عجیب بود که تمام زنان بزرگ داستان تا زمان جین آستن نه تنها از دید جنسیت دیگر، بلکه فقط در رابطه با آن جنسیت مطرح شدهاند». وولف اشاره میکنه که شخصیتهای زن در کتابهای پیشین در رابطه با مرد هویت خودشون رو پیدا میکردن، اونا مادر و دختر و معشوقه و فاحشه و خدمتکار بودن. بنابراین براش مهمه که در کتابی که میخوند به این جمله برخورد: «کلوئه الیویا را دوست داشت». دو زن که در ارتباط با همدیگه مطرح میشن و هویتی از خودشون دارن و به مردها گره زده نشدن. به زبان ساده توی آزمون بکدل موفق شدن.

تناقضی که توی صحبتهاش حس کردم درباره ارزشهای زنانه و مردانه بود. وولف اشاره میکنه که ارزشهای مردانه غالبند - توی گزینگفتهای که ابتدای ریویوم گذاشتم مشخص بود - و نگاهی منتقدانه به کمارزش شمردن تجربیات زنان داره. چیزی که هنوز هم وجود داره؛ دخترهایی که صورتی رو تحقیر میکنن چون رنگی زنانهست و اونها نمیخوان «مثل بقیه دخترها» باشن. چون مثل بقیه دخترها و دخترانه بودن تحقیرآمیزه و چه بیشتر دختری خوشحال میشه اگه بهش بگن متفاوته و رفتارهای پسرانه داره.

وولف اشاره میکنه که «این کتابها از فضائل مردانه تجلیل میکنند، ارزشهای مردانه را تایید و دنیای مردان را توصیف میکنند» و تاریخ رو تاریخ مردان میدونه و جویای دونستن حقایقی از جزئیات زندگی عمومی زنهاست که به گفتهی اون تا قرن هجدهم خبری ازشون نبوده. «در سالهای پایانی قرن هجدهم تغییری رخ داد که اگر قصد داشتم تاریخ را از نو بنویسم، آن را بیشتر توصیف میکردم و به آن بهای بیشتری میدادم تا به جنگهای صلیبی یا جنگهای رُز. زن طبقه متوسط نوشتن را آغاز کرد.» پس میشه گفت وولف نگاهی انتقادی به این جهانِ مردمحورِ کتابها - ادبیات، تاریخ، علم و... - داره: در حالی که گویا خودش هم از این دیدگاهِ حقیر پنداشتن تجربیات زنانه در امان نمونده و دقیقاً تجربیات مردانه رو دارای ارزش نوشتن میدونه. اشاره میکنه که مرد به علت تجربیات بیشترش که محدود به خانه و محل زندگی نیستند، زندگی رو بهتر چشیده و از این رو میتونه بهتر بنویسه. مردان فرصتی برای دیدن جهان و حضور در جامعه دارند در حالی که «خانه» قلمروی زنانه و محدود و به گفتهی شاعری «خانهی بندگی». اگرچه وولف به طرز زیبایی توصیف میکنه که چگونه هر اتاق متفاوته و نیروی خلاقه زنان در هزاران سال در دیوارهای خانه نفوذ کرده، و از زنان میخواد این تجربیات رو با نثری غیرمردانه بنویسند و چه حیف میدونه که زنان بخوان خودشون رو مانند مردان بکنند.

در بخشی از کتاب راوی میبینه که بسیار کتابها درباره زنان به قلم مردان هستند ولی کتابی درباره مردان به قلم زنان وجود نداره. وولف طنزآمیز فکر میکنه که گویا موضوع جنسیت - زن - هرکی بوده رو جلب کرده که دربارهش بنویسه، حتی «مردانی که هیچ صلاحیتی ندارند جز اینکه زن نیستند.» این چیزیه که جان استوارت میل هم توی رسالهش بهش اشاره میکنه، اینکه چطور دانشهایی برای زنان ممنوعند که حتی ابلهترین مرد اجازه فعالیت در اون رو داره. مرد میتونه به راحتی وارد کتابخانه بشه و درباره ذات زنان رساله بنویسه و بدون اینکه ماهی کوچک افکارش رو به علت نشستن روی چمنها بپرونند، بیندیشه؛ بههرحال اون مرد صلاحیت داره چون زن نیست و همین کافیه. هوم؟

وولف خشمگینه، چه نشون بده و چه نه. چه زمانی که بهخاطر محرومیت از ورود به کتابخانه «با عصبانیت از پلهها پایین میآمدم» و چه هنگامی که بهطور خنثی نظریات تحقیرآمیز اندیشمندان در رابطه با زنان رو بررسی میکنه، خشمگینه. میتونم ببینم که هنگام فشار دادن قلم بر کاغذ، جایی از کاغذ رو سوراخ کرده. اما زیاد این رو نشون نمیده. زیر تصاویر رنگارنگ توصیفها و افکار پراکندهش پنهان میکنه و در عوض با امید حرف میزنه. با امید، خشم و التماس از زنان میخواد که فعالیت کنند، بنویسند چون دیگه چقدر میخوان گمنام و نادان باقی بمونن؟ وولف امید داره که پول و اتاقی از آن خود برای اونکه زنان بتونن بنویسن کافی باشه - حالا میدونیم که نیست. خودش هم میدونست که نیست، همونطور که در بخشی از کتاب گفت که دلسردیها واقعاً مهمه و نوابغ به حرفهایی که دربارهشون زده میشه اهمیت میدن. وولف میگه که این دلسردی برای زنان چقدر از دلسردی مردان متفاوت بوده: «دنیا به او همچون مردان نمیگفت اگر میخواهی بنویس، برای من فرقی نمیکند بلکه با قهقهه میپرسید میخواهی بنویسی؟ نوشتهی تو به چه دردی میخورد؟» اما باز هم امید داره.

امید به اینکه سالی پانصد پوند و اتاقی از آن خود کافی باشه.

i’m sorry if this makes me a bad feminist but this was hard to get thru #bored

Lock up your libraries if you like; but there is no gate, no lock, no bolt that you can set upon the freedom of my mind.

–––

وولف در این مقاله، دربارهی اهمیت حضور زنان در ادبیات و در حرفه صحبت میکنه. از این حرف میزنه که چطور زنان در طول تاریخ نادیده گرفته شدن، حذف و کمرنگ شدن و فضایی برای ابراز وجود نداشتهن. تنها نقدی که بهش دارم اینه که روی زن سفیدپوست و معضلات زن سفیدپوست قرن نوزدهمی بحث میکنه و به مسائل زنانی از نژادها و اتنیکهای متفاوت نمیپردازه.

–––

وولف در این مقاله، دربارهی اهمیت حضور زنان در ادبیات و در حرفه صحبت میکنه. از این حرف میزنه که چطور زنان در طول تاریخ نادیده گرفته شدن، حذف و کمرنگ شدن و فضایی برای ابراز وجود نداشتهن. تنها نقدی که بهش دارم اینه که روی زن سفیدپوست و معضلات زن سفیدپوست قرن نوزدهمی بحث میکنه و به مسائل زنانی از نژادها و اتنیکهای متفاوت نمیپردازه.

challenging

funny

informative

slow-paced

hopeful

inspiring

reflective

fast-paced