You need to sign in or sign up before continuing.

Take a photo of a barcode or cover

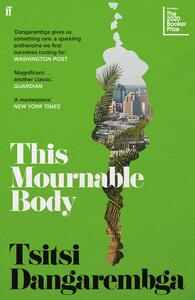

Tsitsi Dangarembga’s novel This Mournable Body reveals the heartbreaking journey blind ambition takes a middle-aged woman on as she strives to make something of herself in a nation attempting to recover from colonialism and falling victim to capitalism. This Mournable Body continues the story of Tambudzai (Tambu) in her mid-thirties as she navigates the newly independent Zimbabwe. As she finally makes strides towards a successful future, a painful event causes Tambu’s mental health to spiral and her struggle to make herself into a successful member of society even more prominent. This book was shortlisted for the 2020 Booker Prize and Dangarembga was awarded the 2021 PEN Pinter Prize for her collection of writings which contain “outstanding literary merit.”

One of most notable things about Dangarembga’s novel is her choice of protagonist. Tambudzai is the epitome of the anti-heroine as she struggles to make a name for herself in the newly independent Zimbabwe. While it is difficult to support a protagonist who repeatedly makes cringe-worthy decisions, she embodies the complexity of a woman attempting to become prosperous in an oppressive society. While Danarembga’s message resonates long after finishing the book, her decision to portray Tambu’s story in what seems to be a second person point of view (an attempt to immerse the reader) often took on an omnipresent feeling of all-knowingness that made the concept of “you” feel somewhat convoluted. Along with this, the train-of-thought style of writing Dangarembga portrays Tambu through makes it feel like the story is dragging on a bit, and when this is combined with the overall somberness of the first two parts of the book, the story can become difficult to digest and stay engaged in. This becomes especially prominent in the more convoluted portions of the book where the author expects the reader to interpret events that just took place or delays an explanation of events until later. This type of writing style resulted in multiple rereads of the same paragraph early in the book, but as I grew accustomed to Dangarembga’s literary preferences, it became easier to keep up with Tambu’s thought process and the author’s exclusion of information.

While there were significant points where Dangarembga’s literary choices made the book difficult to read, these were countered by some incredible uses of Tambu as an antiheroine. One of the genius aspects of having such a complex character who seems to only think in the grey areas of life is it forces the reader to put themselves in their shoes (something I believe could have been done without the omnipresent second person POV the author uses). A reader must genuinely think “Would I have done any better?” “Could I have done any better?” Dangarembga’s novel succeeds in forcing the reader out of their comfort zone in terms of the conflict the protagonist is confronted with. I think my praise for the novel centers around Tambu and the way Dangarembga conveys Tambu’s relationship/growth with/through secondary characters in the novel (some noteworthy ones are Nyasha, Christina, and Mai [Tambu’s Mother]). While the abrupt ending (don’t worry, no spoilers) was something heavily disputed, it is something I appreciated about the novel. The issues introduced and repeated throughout the novel (and series) were not resolved by the end of the story and are still ongoing issues in Zimbabwean society, so why should the novel feel conclusive? It would not stay true to the painful reflection of life as a woman in Zimbabwe that Dangarembga is offering. This ending stayed true to the character and the journey we just followed her on.

While my personal preferences of the author’s literary choices made it a slower read for me and may have lessened its “rating” in the long run, this cannot overshadow the economical and social significance in the story Dangarembga is sharing. The damaging patriarchal situations conveyed by Tambu as an “outsider” (in most situations) is relatable to a wide range of readers, and the damage of turning an entire culture into an opportunity for ecotourism and capitalistic gain is still prominent in modern society. Along with the blatant nods to gender roles, the role of racism and capitalism, Dangarembga makes small mentions of mental health care (a [should-be] basic human right that is denied to many around the world), cultural tensions, and social obligations. The cocktail of social issues that makes up This Mournable Body makes it an important read for a wide range of audiences, but may resonate more with females, people of color, and fans of historical fiction (although I think the information being shared is relevant and could allow for more exposure/cultural understanding for all races). Overall, Dangarembga shows the development of a woman trying to survive in a society build to oppress her and, no matter the reader, Tambu’s story and the ubiquitous themes presented within it will leave something to resonate with.

One of most notable things about Dangarembga’s novel is her choice of protagonist. Tambudzai is the epitome of the anti-heroine as she struggles to make a name for herself in the newly independent Zimbabwe. While it is difficult to support a protagonist who repeatedly makes cringe-worthy decisions, she embodies the complexity of a woman attempting to become prosperous in an oppressive society. While Danarembga’s message resonates long after finishing the book, her decision to portray Tambu’s story in what seems to be a second person point of view (an attempt to immerse the reader) often took on an omnipresent feeling of all-knowingness that made the concept of “you” feel somewhat convoluted. Along with this, the train-of-thought style of writing Dangarembga portrays Tambu through makes it feel like the story is dragging on a bit, and when this is combined with the overall somberness of the first two parts of the book, the story can become difficult to digest and stay engaged in. This becomes especially prominent in the more convoluted portions of the book where the author expects the reader to interpret events that just took place or delays an explanation of events until later. This type of writing style resulted in multiple rereads of the same paragraph early in the book, but as I grew accustomed to Dangarembga’s literary preferences, it became easier to keep up with Tambu’s thought process and the author’s exclusion of information.

While there were significant points where Dangarembga’s literary choices made the book difficult to read, these were countered by some incredible uses of Tambu as an antiheroine. One of the genius aspects of having such a complex character who seems to only think in the grey areas of life is it forces the reader to put themselves in their shoes (something I believe could have been done without the omnipresent second person POV the author uses). A reader must genuinely think “Would I have done any better?” “Could I have done any better?” Dangarembga’s novel succeeds in forcing the reader out of their comfort zone in terms of the conflict the protagonist is confronted with. I think my praise for the novel centers around Tambu and the way Dangarembga conveys Tambu’s relationship/growth with/through secondary characters in the novel (some noteworthy ones are Nyasha, Christina, and Mai [Tambu’s Mother]). While the abrupt ending (don’t worry, no spoilers) was something heavily disputed, it is something I appreciated about the novel. The issues introduced and repeated throughout the novel (and series) were not resolved by the end of the story and are still ongoing issues in Zimbabwean society, so why should the novel feel conclusive? It would not stay true to the painful reflection of life as a woman in Zimbabwe that Dangarembga is offering. This ending stayed true to the character and the journey we just followed her on.

While my personal preferences of the author’s literary choices made it a slower read for me and may have lessened its “rating” in the long run, this cannot overshadow the economical and social significance in the story Dangarembga is sharing. The damaging patriarchal situations conveyed by Tambu as an “outsider” (in most situations) is relatable to a wide range of readers, and the damage of turning an entire culture into an opportunity for ecotourism and capitalistic gain is still prominent in modern society. Along with the blatant nods to gender roles, the role of racism and capitalism, Dangarembga makes small mentions of mental health care (a [should-be] basic human right that is denied to many around the world), cultural tensions, and social obligations. The cocktail of social issues that makes up This Mournable Body makes it an important read for a wide range of audiences, but may resonate more with females, people of color, and fans of historical fiction (although I think the information being shared is relevant and could allow for more exposure/cultural understanding for all races). Overall, Dangarembga shows the development of a woman trying to survive in a society build to oppress her and, no matter the reader, Tambu’s story and the ubiquitous themes presented within it will leave something to resonate with.

I went in to this one before I saw that it was part of a trilogy, which may explain some of the disconnect I had with it / main character. Kinda loved that it was written in second person—has a different effect!

A book about the difficulties of persisting when the odds are stacked against you. This Mournable Body follows the life of Tambudzai in Harare, Zimbabwe, and deals intensely with themes of failure as she struggles throughout with living up to the expectations she and her family once set for herself. It definitely helped me gain an insight into the strain of every-day life in postcolonial Zimbabwe, which is not always safe or welcoming for a young woman. At times I found the events difficult to follow, the majority being implied and often heavily metaphorical. It is also worth uttering a caution that this book is not very hopeful (maybe it has to be this way). Nevertheless, a compelling read.

Also includes some interesting discourse around the intrusion of Western values and the sometimes exoticising gaze. And for the English lit nerds: Dangarembga writes in second person, present tense, which definitely pulls you right in.

Also includes some interesting discourse around the intrusion of Western values and the sometimes exoticising gaze. And for the English lit nerds: Dangarembga writes in second person, present tense, which definitely pulls you right in.

It’s hard to imagine the Tambu of Nervous Conditions inside the Tambu of this book, despite many aspects of her life path also seeming painfully inevitable.

Dangarembga is a master at the unreliable perspective from which Tambu views the world: we see the strong Nyasha reduced to a whining wife and the opportunistic Tracey placed on a pedestal through Tambu’s eyes. We see also a breakdown of the narration when Tambu breaks down herself.

Everything in this book is a skillfully rendered punch in the gut, told by someone at once rather unlikeable and wholly sympathetic. Despite how tough it was to read, I’m glad I made my way through this trilogy.

Dangarembga is a master at the unreliable perspective from which Tambu views the world: we see the strong Nyasha reduced to a whining wife and the opportunistic Tracey placed on a pedestal through Tambu’s eyes. We see also a breakdown of the narration when Tambu breaks down herself.

Everything in this book is a skillfully rendered punch in the gut, told by someone at once rather unlikeable and wholly sympathetic. Despite how tough it was to read, I’m glad I made my way through this trilogy.

Tambudzai begins the novel in a youth hostel in Harare, anxiously contemplating how she will find a new job having quit her role as a copywriter after her white colleagues kept receiving recognition for her work. What purports to be an examination of psychological decline picks itself back up time and time again as Tambudzai relentlessly pursues a notion of respectability and progress that she feels are at times in grasp, but mostly desperately out of reach.

Written in second person, the novel is cloistered by its incessant 'you' which interestingly, adds a layer of distance between Tambudzai and her own identity. Her sense of self is a constant reiteration, something that she must remind herself of frequently but with little confidence. Having had the benefit of a good education, Tambudzai's feeling that she has fallen short of projected expectations haunts her as she takes halting steps towards stability - financially and of peace of mind.

I did not realise that I had picked up a book belonging to a series so I must preface my thoughts by acknowledging that I would likely have taken more from this novel and enjoyed its nuances more if I had been familiar with the preceding texts. However, I really did not enjoy the second-person narrative which felt jarring and took time to adjust to. While it made perfect sense for the narrative to be disjointed, slightly unfamiliar, even confusing at points due to Tambudzai's mental state, I felt like I was constantly chasing the end of the thread which I had dropped somewhere earlier. There were moments that were truly moving and emotionally rendered - where Tambudzai would reckon with her own disillusionment about her future and the disjunction between the person she imagined she might be growing from her former self, and the person she had actually become.

Like Tambudzai herself, the young country of Zimbabwe is finding its feet and this uneasy state of newness is palpable in Dangarembga's descriptions which are suitably rich and evocative: a city brimming with its recent history, racial tensions stirring and bids for prosperity in this brave, new world a dime a dozen. Tambudzai's job at the eco-tourism office vies for office space with several other businesses seeking to establish themselves. At the heart of this novel is the idea of betrayal: the ways in which an emerging nation can betray its ideals, and the way we can betray our own convictions and beyond that, betray ourselves.

I did not mesh well with the writing style of this novel and I did have to push myself to finish it but I felt it was delivering a very meaningful commentary that I might otherwise have enjoyed in a different form although I recognise the arguments for the the one it took shape in.

Written in second person, the novel is cloistered by its incessant 'you' which interestingly, adds a layer of distance between Tambudzai and her own identity. Her sense of self is a constant reiteration, something that she must remind herself of frequently but with little confidence. Having had the benefit of a good education, Tambudzai's feeling that she has fallen short of projected expectations haunts her as she takes halting steps towards stability - financially and of peace of mind.

I did not realise that I had picked up a book belonging to a series so I must preface my thoughts by acknowledging that I would likely have taken more from this novel and enjoyed its nuances more if I had been familiar with the preceding texts. However, I really did not enjoy the second-person narrative which felt jarring and took time to adjust to. While it made perfect sense for the narrative to be disjointed, slightly unfamiliar, even confusing at points due to Tambudzai's mental state, I felt like I was constantly chasing the end of the thread which I had dropped somewhere earlier. There were moments that were truly moving and emotionally rendered - where Tambudzai would reckon with her own disillusionment about her future and the disjunction between the person she imagined she might be growing from her former self, and the person she had actually become.

Like Tambudzai herself, the young country of Zimbabwe is finding its feet and this uneasy state of newness is palpable in Dangarembga's descriptions which are suitably rich and evocative: a city brimming with its recent history, racial tensions stirring and bids for prosperity in this brave, new world a dime a dozen. Tambudzai's job at the eco-tourism office vies for office space with several other businesses seeking to establish themselves. At the heart of this novel is the idea of betrayal: the ways in which an emerging nation can betray its ideals, and the way we can betray our own convictions and beyond that, betray ourselves.

I did not mesh well with the writing style of this novel and I did have to push myself to finish it but I felt it was delivering a very meaningful commentary that I might otherwise have enjoyed in a different form although I recognise the arguments for the the one it took shape in.

challenging

dark

tense

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Complicated

Loveable characters:

No

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

I did not actually realise that This Mournable Body is part of a series until I looked up Dangarembga on Wikipedia. This bold slice-of-life novel stands well on its own too, though, so I doubt my reading experience was hindered by not having read the two previous books in the series - though I'm sure having done so would have deepened my understanding of our main character, Tambudzai.

This Mournable Body is a clear-eyed look at the often hollow promise of upwards mobility and success, an exploration of mental health, women in the workplace, and the meaning of family at the crossroads of success and work-life-balance. Tambudzai is a strong main character, which is a great feat of Dangarembga's writing as the entire novel is written in second person - in a way, Tambu is you, yet she is still Tambu in her own right. The lines between Tambu and the reader are blurred, sure, but they're still not nonexistent, and while the second person narration brings you closer to being her voice, it is still distinct enough to forefront Tambu's story. At first, I really struggled with the narrating style, but after a while it became a natural part of the book and did not bother me that much.

While I really adored Tambu as a character, I ultimately think This Mournable Body could have done with some editing down. Dangarembga approaches her themes and topics with grace, but I feel like this would have been a much more impactful reading experience if it did not contain as much as it did, which would have given space for the plot points and themes to grow more naturally. There is also a lack of a feeling of continuity in the plot that made this book feel rather disjointed to me, which is interesting because Dangarembga definitely does not just drop things and leave them as they lay, but in the end the structure of the novel is so that things feel abandoned in a way.

Overall, This Mournable Body is a strong 3-star read for me, and one that might benenit from a reread in the future. I enjoyed a lot of things in this novel, but other aspects left me wanting more, so I think 3 stars is the perfect representation of how I feel about this one.

This Mournable Body is a clear-eyed look at the often hollow promise of upwards mobility and success, an exploration of mental health, women in the workplace, and the meaning of family at the crossroads of success and work-life-balance. Tambudzai is a strong main character, which is a great feat of Dangarembga's writing as the entire novel is written in second person - in a way, Tambu is you, yet she is still Tambu in her own right. The lines between Tambu and the reader are blurred, sure, but they're still not nonexistent, and while the second person narration brings you closer to being her voice, it is still distinct enough to forefront Tambu's story. At first, I really struggled with the narrating style, but after a while it became a natural part of the book and did not bother me that much.

While I really adored Tambu as a character, I ultimately think This Mournable Body could have done with some editing down. Dangarembga approaches her themes and topics with grace, but I feel like this would have been a much more impactful reading experience if it did not contain as much as it did, which would have given space for the plot points and themes to grow more naturally. There is also a lack of a feeling of continuity in the plot that made this book feel rather disjointed to me, which is interesting because Dangarembga definitely does not just drop things and leave them as they lay, but in the end the structure of the novel is so that things feel abandoned in a way.

Overall, This Mournable Body is a strong 3-star read for me, and one that might benenit from a reread in the future. I enjoyed a lot of things in this novel, but other aspects left me wanting more, so I think 3 stars is the perfect representation of how I feel about this one.

"Now you understand. You arrived on the back of a hyena. The treacherous creature dropped you from above onto a desert floor. There is nothing here except, at the floor's limits, infinite walls.

You are an ill-made person. You are being unmade."

Thirty years after the publication of Nervous Conditions Tsitsi Dangarembga brings her trilogy to a fulminant end. At the beginning of This Mournable Body, Tambudzai has left her job as a copywriter. She lives from her meagre savings and stays at a women's hostel - where the board complains she is too old. Tambudzai knows she has to refocus and get her life together; her anxiety about being forced to go back to the homestead as present as ever.

Dangarembga shows once again that she knows how to paint intricate portrays of women's psyches. This is not a particularly easy read. Tambudzai is may be at her lowest yet and it is hard to always empathise with her, especially because she herself is often judgmental and harsh to the women around her. But at the same time, this makes her a fascinating character. Her actions and thoughts are the results of her struggles, traumas, and her still reigning ambition. The violence is often written opaquely, making you re-read parts to gather the horror and thus making it even more effective and mirroring the underlying patriarchal and (post)colonial violence. Dangarembga is also very good at writing very tension, I felt the anxiety almost creep into my body. Having the entire narrative in 2nd-person supports this direct attack on the reader.

This Mournable Body looks at post-independence Zimbabwe and dissects the lives of Zimbabwean women - from former fighters for independence to women who studied abroad. In the end, Tambudzai has to make difficult decisions and find ways to cope if not even heal. How much more is she willing to give up?

You are an ill-made person. You are being unmade."

Thirty years after the publication of Nervous Conditions Tsitsi Dangarembga brings her trilogy to a fulminant end. At the beginning of This Mournable Body, Tambudzai has left her job as a copywriter. She lives from her meagre savings and stays at a women's hostel - where the board complains she is too old. Tambudzai knows she has to refocus and get her life together; her anxiety about being forced to go back to the homestead as present as ever.

Dangarembga shows once again that she knows how to paint intricate portrays of women's psyches. This is not a particularly easy read. Tambudzai is may be at her lowest yet and it is hard to always empathise with her, especially because she herself is often judgmental and harsh to the women around her. But at the same time, this makes her a fascinating character. Her actions and thoughts are the results of her struggles, traumas, and her still reigning ambition. The violence is often written opaquely, making you re-read parts to gather the horror and thus making it even more effective and mirroring the underlying patriarchal and (post)colonial violence. Dangarembga is also very good at writing very tension, I felt the anxiety almost creep into my body. Having the entire narrative in 2nd-person supports this direct attack on the reader.

This Mournable Body looks at post-independence Zimbabwe and dissects the lives of Zimbabwean women - from former fighters for independence to women who studied abroad. In the end, Tambudzai has to make difficult decisions and find ways to cope if not even heal. How much more is she willing to give up?

forgot to add this when i read it!

i thought the portrayal of ptsd was interesting, very moving; and once again the writing style was delightful. liked it

"you watch the expertise of her fingers enviously as she strips off lengths of black rubber, repairing the hosepipe from her bounty. deftly, she lays the hose spout at the highest point of a seedling bed while she swings a hoe. she waters the sweet peas around the widow's cottage. she sweeps the students' slab. she replants a patch of grass under the guava tree. she is a woman who is good at what she does. and this is intriguing. the new woman does not sweat, nor do you see her out of breath. she is too calm at every task as though her core has fled to a distant place disconnected from her body. her look, hidden under her bland expression, travels far beyond the widow's cottage. she stares down the shaft of her gaze as though when the time comes she will weave herself into it to slide away to a place where vision coincides with a deep wanting. you have seen this manner before, this being where the body is and not being there, in your sister netsai, who went to war, who lost a leg, and who said to you when they said there was peace, 'yes, i went and i am here but i never came back. most of the time i'm still out there wandering through the grass and sand, looking for my leg."

"it is now too late to begin the conversation you should have had weeks ago, when chrisitine came, concerning your family and their need and your inability to do anything about those needs because of your city poverty. christine has that layer under her skin that cuts off her outside from her inside and allows no communication between the person she once believed she could be and the person she has in fact become. the one does not acknowledge the other's existence. the women from war are like that, a new kind of being that no one knew before, not exactly male but no longer female. it is rumoured the blood stopped flowing to their wombs the first time they killed a person. people whisper that the unspeakable acts were even more iniquitous when performed by women, so that the ancestors tied up the nation's prosperity in repugnance at the awfulness of it, just as they had done to the women's wombs. it occurs to you that you are more like christine than you are like mai manyanga: christine with her fruitless war that brought nothing but false hope and a fresh, more complete variety of discouragement. you with your worthless education intensifying your beggary, making it all the more ludicrous."

"'my child, tambu' says mainini. 'war just shrinks in peacetime, isn't it? that's what i saw. i just went into that little space that is still there. so how can kiri and i be useless?'"

i thought the portrayal of ptsd was interesting, very moving; and once again the writing style was delightful. liked it

"you watch the expertise of her fingers enviously as she strips off lengths of black rubber, repairing the hosepipe from her bounty. deftly, she lays the hose spout at the highest point of a seedling bed while she swings a hoe. she waters the sweet peas around the widow's cottage. she sweeps the students' slab. she replants a patch of grass under the guava tree. she is a woman who is good at what she does. and this is intriguing. the new woman does not sweat, nor do you see her out of breath. she is too calm at every task as though her core has fled to a distant place disconnected from her body. her look, hidden under her bland expression, travels far beyond the widow's cottage. she stares down the shaft of her gaze as though when the time comes she will weave herself into it to slide away to a place where vision coincides with a deep wanting. you have seen this manner before, this being where the body is and not being there, in your sister netsai, who went to war, who lost a leg, and who said to you when they said there was peace, 'yes, i went and i am here but i never came back. most of the time i'm still out there wandering through the grass and sand, looking for my leg."

"it is now too late to begin the conversation you should have had weeks ago, when chrisitine came, concerning your family and their need and your inability to do anything about those needs because of your city poverty. christine has that layer under her skin that cuts off her outside from her inside and allows no communication between the person she once believed she could be and the person she has in fact become. the one does not acknowledge the other's existence. the women from war are like that, a new kind of being that no one knew before, not exactly male but no longer female. it is rumoured the blood stopped flowing to their wombs the first time they killed a person. people whisper that the unspeakable acts were even more iniquitous when performed by women, so that the ancestors tied up the nation's prosperity in repugnance at the awfulness of it, just as they had done to the women's wombs. it occurs to you that you are more like christine than you are like mai manyanga: christine with her fruitless war that brought nothing but false hope and a fresh, more complete variety of discouragement. you with your worthless education intensifying your beggary, making it all the more ludicrous."

"'my child, tambu' says mainini. 'war just shrinks in peacetime, isn't it? that's what i saw. i just went into that little space that is still there. so how can kiri and i be useless?'"