Take a photo of a barcode or cover

fast-paced

En god bog med meget fine personskildringer. Ida Jessen læser selv op i den lydbogsudgave jeg er heldig at have fået fat på, det er en nydelse.

This book was definitely not for me. I found it too slow and nothing really happens in the book. I really like the overall idea or a woman who loses her husband and is on a journey of self discovery. But the prose is so dull. I think the issue may be in the translation.

Läs min recension på bloggen: http://www.fiktiviteter.se/2018/03/09/en-ny-tid-av-ida-jessen/

emotional

reflective

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

I feel like a person standing in a landscape so empty and open that it matters not a bit in which direction I choose to go. There would be no difference: north, south, east or west, it would be the same wherever I went.

Thyregod, Denmark at the beginning of the 20th Century. Through diary entries, Ida Jessen conveys the life of a schoolteacher, Lilly Høy, starting with recounts of her visits to her husband Vigand Bagge who is in the hospital in another town, over her response to his death and her attempts to build herself a new life, find herself a new place and identity in the rural community she is living in and find attachment to her life again.

Slowly, as Lilly through subtle allusions, flashbacks, encounters and meaningful silences discloses her past, Lilly’s life turns out to have been far less conventional than one would have expected for a woman living at that time in such a remote rural place. Before she came to live in Thyregod where she met her husband, Lilly was a vivid and intelligent student, who moved to the rural village to put her ideals as a teacher into practise. Contemplating on the past and the present now she is alone, she reflects on her relationship with Vigand, her spouse for 22 years, who was a district physician ‘for fourteen impoverished and far-flung parishes’ – a stern, taciturn, stoic man, thirty years her elder and emotionally aloof – painting a portrait of their marriage in which tiny anecdotes and moments illustrate their inability to connect, revealing Lilly’s struggle with finding a way to live together with her husband, from her angling for a tender word or a caress to her walking on eggshells not to speak a word that would lead to more marital scorn.

Can one ask a person to show that they love you? Reason, that most faithful onlooker to the tribulations of others, says no.

But what says unreason?

There is the mourning for the person her husband was, but also the grieving for the lost life, the grieving for the lost self, a confrontation with the sacrifices made, the self-repression. The voice and thoughts of the one she has lived together with for such a long time continue to resonate in her own thoughts and acts, tending to censure and curb her, showing the slowness and necessity of the process of dislodging. Her grief is in several respects equivocal, mirroring the nature of the marriage (who told me it is worse to be lonely with two than alone?).

In my darkest moments I understand only too well what misfortune can leave a person in such a place. Bitterness is a very soft and comfortable armchair from which it is difficult indeed to extract oneself once one has decided to settle in it.

The portrait of Lilly and her current life and past which drop by drop forms in the mind of the reader is finely constructed, the silences, understatement and twofold interruptions in the stream of the diary are eloquent as well as potent.

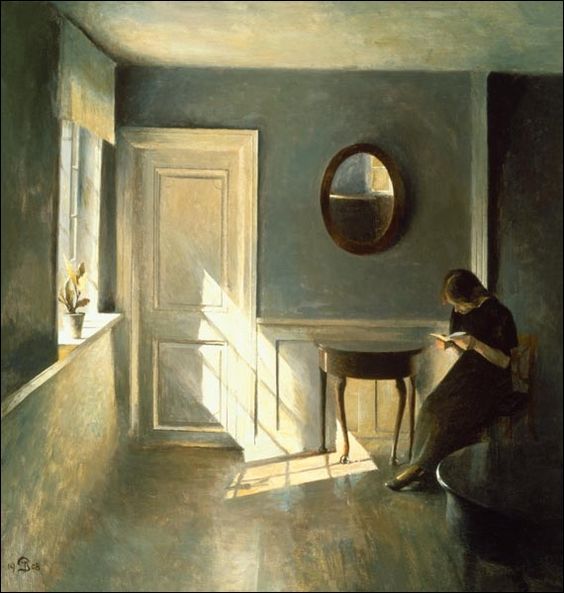

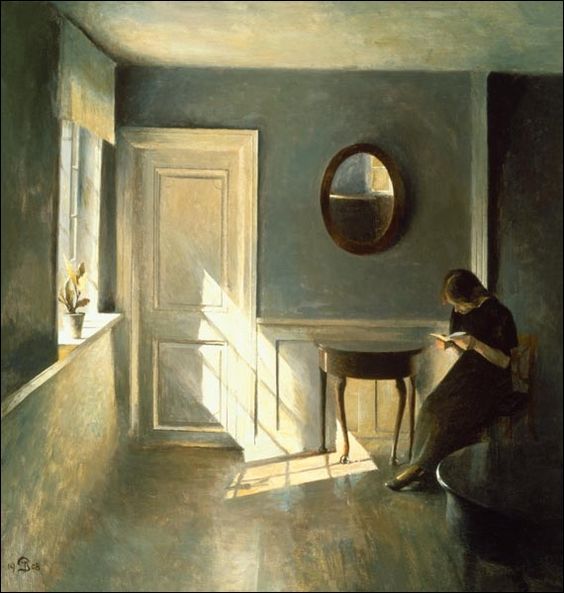

Reading Jessen’s articulate and luminous sentences drew me into the wintry silence of Lilly’s evenings, sitting alone at home, evoking the inwardness of the story magnificently. I smiled at the thought of myself as a woman reading about another woman alone in a silent house at night who also reads in silence, under a lamp – like looking at a painting depicting a person looking at a painting on which someone is looking at a painting.

No love is ever without grief.

Apart from the masterly evocation of the restrained emotions and inner experiences of growth and regained freedom of a woman who gets widowed, the novel through the description of everyday life and Lilly Høy’s personal history throws a light on the geography and history of the rural, poor area and life in a small village community in Denmark early 20th century (the diary spans the period 1904-1932) and the social changes taking place during that time (as aptly illustrated by Laura’s review), developments in which both spouses will play their part. And so the title of the novel ‘A change of time’ (literally from the Danish ‘A new time’) has a dual significance: both for Lilly Høy and for the village community dawns a new life, characterised by change and modernity.

Beautifully slow-paced, poetic and atmospheric, as an intimate meditation on how life goes on after the death of a spouse, A change of time reminded me of [b:Often I Am Happy|40766163|Often I Am Happy|Jens Christian Grøndahl|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1531133409l/40766163._SY75_.jpg|52112490] by Ida Jessen’s compatriot Jens Christian Grøndahl. As much as I loved Grøndahl’s novel, Ida Jessen’s novel touched me even more profoundly by its quiet finesse, elegant prose and subtle depiction of its social context and while reading, I marked numerous sentences that struck me for their insightfulness, honesty and truth. Though quite different, both novels hold a gratifying and heartening ending: Grøndahl’s empowering, Jessen’s of an embracing warmth and tenderness that made me vicariously glow in the dark.

A warmth unfolded and spread – I know now that it was tenderness.

My heart runs ahead of me. And I run after my heart. I cannot be without it.

While typing this review , I discovered that Ida Jessen wrote a pendant to Lilly’s story, this time seen from the perspective of her husband, Vigand ([b:Doktor Bagges anagrammer|33805880|Doktor Bagges anagrammer|Ida Jessen|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1484412103l/33805880._SY75_.jpg|54710013]). I like that premise of creating a diptych embodying an in-depth exploration of his personality by offering him the chance to tell his side of the story and I would love to read that book too if it happens to get translated in English or Dutch. My honest thanks to Net Galley, Edelweiss, Archipelago and Ida Jessen for the review copy of this novel – this excursion to Danish contemporary literature turned out a truly rewarding one.

(Paintings, as the one on the cover of the novel, by Vilhelm Hammershøi)

Thyregod, Denmark at the beginning of the 20th Century. Through diary entries, Ida Jessen conveys the life of a schoolteacher, Lilly Høy, starting with recounts of her visits to her husband Vigand Bagge who is in the hospital in another town, over her response to his death and her attempts to build herself a new life, find herself a new place and identity in the rural community she is living in and find attachment to her life again.

Slowly, as Lilly through subtle allusions, flashbacks, encounters and meaningful silences discloses her past, Lilly’s life turns out to have been far less conventional than one would have expected for a woman living at that time in such a remote rural place. Before she came to live in Thyregod where she met her husband, Lilly was a vivid and intelligent student, who moved to the rural village to put her ideals as a teacher into practise. Contemplating on the past and the present now she is alone, she reflects on her relationship with Vigand, her spouse for 22 years, who was a district physician ‘for fourteen impoverished and far-flung parishes’ – a stern, taciturn, stoic man, thirty years her elder and emotionally aloof – painting a portrait of their marriage in which tiny anecdotes and moments illustrate their inability to connect, revealing Lilly’s struggle with finding a way to live together with her husband, from her angling for a tender word or a caress to her walking on eggshells not to speak a word that would lead to more marital scorn.

Can one ask a person to show that they love you? Reason, that most faithful onlooker to the tribulations of others, says no.

But what says unreason?

There is the mourning for the person her husband was, but also the grieving for the lost life, the grieving for the lost self, a confrontation with the sacrifices made, the self-repression. The voice and thoughts of the one she has lived together with for such a long time continue to resonate in her own thoughts and acts, tending to censure and curb her, showing the slowness and necessity of the process of dislodging. Her grief is in several respects equivocal, mirroring the nature of the marriage (who told me it is worse to be lonely with two than alone?).

In my darkest moments I understand only too well what misfortune can leave a person in such a place. Bitterness is a very soft and comfortable armchair from which it is difficult indeed to extract oneself once one has decided to settle in it.

The portrait of Lilly and her current life and past which drop by drop forms in the mind of the reader is finely constructed, the silences, understatement and twofold interruptions in the stream of the diary are eloquent as well as potent.

Reading Jessen’s articulate and luminous sentences drew me into the wintry silence of Lilly’s evenings, sitting alone at home, evoking the inwardness of the story magnificently. I smiled at the thought of myself as a woman reading about another woman alone in a silent house at night who also reads in silence, under a lamp – like looking at a painting depicting a person looking at a painting on which someone is looking at a painting.

No love is ever without grief.

Apart from the masterly evocation of the restrained emotions and inner experiences of growth and regained freedom of a woman who gets widowed, the novel through the description of everyday life and Lilly Høy’s personal history throws a light on the geography and history of the rural, poor area and life in a small village community in Denmark early 20th century (the diary spans the period 1904-1932) and the social changes taking place during that time (as aptly illustrated by Laura’s review), developments in which both spouses will play their part. And so the title of the novel ‘A change of time’ (literally from the Danish ‘A new time’) has a dual significance: both for Lilly Høy and for the village community dawns a new life, characterised by change and modernity.

Beautifully slow-paced, poetic and atmospheric, as an intimate meditation on how life goes on after the death of a spouse, A change of time reminded me of [b:Often I Am Happy|40766163|Often I Am Happy|Jens Christian Grøndahl|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1531133409l/40766163._SY75_.jpg|52112490] by Ida Jessen’s compatriot Jens Christian Grøndahl. As much as I loved Grøndahl’s novel, Ida Jessen’s novel touched me even more profoundly by its quiet finesse, elegant prose and subtle depiction of its social context and while reading, I marked numerous sentences that struck me for their insightfulness, honesty and truth. Though quite different, both novels hold a gratifying and heartening ending: Grøndahl’s empowering, Jessen’s of an embracing warmth and tenderness that made me vicariously glow in the dark.

A warmth unfolded and spread – I know now that it was tenderness.

My heart runs ahead of me. And I run after my heart. I cannot be without it.

While typing this review , I discovered that Ida Jessen wrote a pendant to Lilly’s story, this time seen from the perspective of her husband, Vigand ([b:Doktor Bagges anagrammer|33805880|Doktor Bagges anagrammer|Ida Jessen|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1484412103l/33805880._SY75_.jpg|54710013]). I like that premise of creating a diptych embodying an in-depth exploration of his personality by offering him the chance to tell his side of the story and I would love to read that book too if it happens to get translated in English or Dutch. My honest thanks to Net Galley, Edelweiss, Archipelago and Ida Jessen for the review copy of this novel – this excursion to Danish contemporary literature turned out a truly rewarding one.

(Paintings, as the one on the cover of the novel, by Vilhelm Hammershøi)

This is a little gem that, apparently, is not widely read yet. Danish author Ida Jessen (°1964) has only written a limited oeuvre, but judging by this book, she is certainly worth keeping an eye on. In itself, this are no more than diary entries by Fru Bagge, Mrs Bagge, maiden name Lilly, from approximately 1927 to 1934. The start seems dramatic: her husband Vigand, a widely respected doctor, dies and Lilly – who had devoted her entire life to him – does not seem to know what to do. But from the very beginning it is clear that there was quite a distance between the two and that Vigand in particular was a cold, distant man, almost gruesomely so. The diary entries are a mixture of flashbacks to their special marriage (she was 20 years younger than him), sometimes bitter musings about what she really wanted in life and did not get, and considerations on building a new life as a widow. In other words: this is highly introspective. Lilly is a very observant, thoughtful woman who accepts her fate, but ultimately – after deep thought – retains enough strength to get back on her feet. Just look at this truly fabulous quote, which should be close to many of us: “Bitterness is a very soft and comfortable armchair from which it is difficult indeed to extract oneself once one has decided to settle in it.” Indirectly, this book gives us an idea of the sober life in the Danish countryside at the beginning of the 20th century (including the introduction of elements of modernity). But it is mainly the struggle of women with social conventions, their attempts to give their lives fulfillment, that are central. Jessen writes soberly and minimalistic, perhaps deliberately so, because that modesty makes this book extra powerful. Only the sudden twist in the final chapter, a kind of deus ex machina, disappointed me slightly. But this book and this writer are definitely a discovery.

"The hour is late. A short while ago I stood outside on the front step. The street lights are extinguished now, and the lamp on the station's gable end. If a person knew no better, they might think there were no streets at all, no houses, no people, no dogs. No fields ploughed, no hen coops, no sheds. One might think it all reclaimed by the heath. Or that we had never been here."

emotional

reflective

fast-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

She described complex feelings and emotion, that I never knew how to describe, so simply, with one or two words, and ye I knew exactly what she meant. Such a light and simple, yet complex story, without unnecessary over explaination.

En helt anekdotisk iakttagelse: Historiska romaner handlar till 70% om de två världskrigen (där det senare är i majoritet). Sedan har vi 10% som rör sig i krigisk antik, 10% i gotisk medeltid och 9% i slott under 17- eller 1800-tal.

Ida Jessen siktade in sig på den sista procenten, och träffade så gott som mitt i prick. Vilket en inte kan tro om en får höra huvuddragen; tidigt 1900-tal, lantligt danskt hedlandskap, där inga särskilda historiska händelser alls ägt eller ska äga rum. Bara en vanlig kvinna - gumma tror jag först, men hon är bara 50 när hon blir änka och berättelsen tar fart. Eller - den tar aldrig fart. Den puttrar på. Språket är enkelt, nästan torftigt, precis som miljön. Och - som sagt - mitt i prick.

Det här är jättefint, och jag tycker mycket om Lilly.

Ida Jessen siktade in sig på den sista procenten, och träffade så gott som mitt i prick. Vilket en inte kan tro om en får höra huvuddragen; tidigt 1900-tal, lantligt danskt hedlandskap, där inga särskilda historiska händelser alls ägt eller ska äga rum. Bara en vanlig kvinna - gumma tror jag först, men hon är bara 50 när hon blir änka och berättelsen tar fart. Eller - den tar aldrig fart. Den puttrar på. Språket är enkelt, nästan torftigt, precis som miljön. Och - som sagt - mitt i prick.

Det här är jättefint, och jag tycker mycket om Lilly.