Take a photo of a barcode or cover

mars2k's Reviews (234)

Graphic: Racial slurs

Moderate: Child abuse, Confinement, Cursing, Drug use, Infidelity, Panic attacks/disorders, Physical abuse, Racism, Sexual content, Torture, Violence, Police brutality, Kidnapping

Minor: Ableism, Addiction, Cancer, Death, Gun violence, Hate crime, Rape, Blood, Dementia, Death of parent, Murder, Schizophrenia/Psychosis , Pregnancy, Fire/Fire injury, Alcohol

Graphic: Cursing

Moderate: Death, Drug use, Panic attacks/disorders, Blood, Excrement, Death of parent

Minor: Animal death, Body horror, Bullying, Chronic illness, Fatphobia, Mental illness, Sexual content, Suicide, Vomit, Medical content, Grief, War

Graphic: Animal death, Cancer, Child abuse, Cursing, Death, Gun violence, Racial slurs, Violence, Blood, Murder, Fire/Fire injury, War

Moderate: Ableism, Adult/minor relationship, Body horror, Bullying, Child death, Domestic abuse, Drug use, Gore, Homophobia, Infertility, Infidelity, Misogyny, Racism, Rape, Sexual assault, Terminal illness, Toxic relationship, Forced institutionalization, Xenophobia, Police brutality, Antisemitism, Kidnapping, Stalking, Lesbophobia, Injury/Injury detail, Classism

Minor: Addiction, Alcoholism, Confinement, Fatphobia, Pedophilia, Suicide, Excrement, Vomit, Car accident, Abortion, Death of parent, Pregnancy, Outing, Cultural appropriation, Abandonment, Alcohol

Perhaps if I’d seen Death of a Salesman performed instead of reading the script I’d have had a more profound experience. As it stands, I can give a noncommittal shrug and confess it said what Miller wanted it to say but it didn’t speak to me.

Moderate: Ableism, Bullying, Child abuse, Death, Emotional abuse, Infidelity, Misogyny, Sexism, Suicide, Toxic relationship, Violence, Dementia, Grief, Car accident, Death of parent, Schizophrenia/Psychosis

Minor: Cursing, Domestic abuse, Fatphobia, Sexual content, Vomit, Suicide attempt, Fire/Fire injury, War

Graphic: Animal cruelty, Confinement, Death, Torture, Toxic relationship, Xenophobia, Blood, Abandonment

Moderate: Adult/minor relationship, Animal death, Child abuse, Eating disorder, Emotional abuse, Gun violence, Physical abuse, Self harm, Sexual assault, Violence, Islamophobia, Grief, Death of parent, Murder, Injury/Injury detail

Minor: Ableism, Body horror, Incest, Misogyny, Panic attacks/disorders, Racism, Sexual content, Suicidal thoughts, Suicide, Excrement, Vomit, Dementia, Pregnancy, Cultural appropriation, Alcohol, Colonisation, War, Classism

All in all, a fairly middling assortment. Worthwhile if you’re interested in the history of science fiction, I suppose.

Graphic: Ableism, Alcoholism, Animal cruelty, Animal death, Body horror, Bullying, Death, Genocide, Gore, Gun violence, Mental illness, Physical abuse, Racial slurs, Racism, Slavery, Violence, Blood, Medical content, Grief, Mass/school shootings, Medical trauma, Car accident, Murder, Schizophrenia/Psychosis , Fire/Fire injury, Alcohol, Colonisation, War

Moderate: Child abuse, Confinement, Emotional abuse, Misogyny, Self harm, Suicidal thoughts, Suicide, Terminal illness, Torture, Xenophobia, Police brutality, Antisemitism, Cannibalism, Stalking, Suicide attempt, Injury/Injury detail, Classism

Minor: Child death, Sexism, Sexual content, Islamophobia, Death of parent, Lesbophobia

I wouldn’t recommend Too Big to Walk

Moderate: Animal death, Child death, Death, Sexism, Sexual content, Blood, Fire/Fire injury, Colonisation, War

Minor: Ableism, Addiction, Alcoholism, Bullying, Cancer, Chronic illness, Cursing, Drug use, Genocide, Gore, Gun violence, Misogyny, Slavery, Suicide, Terminal illness, Xenophobia, Excrement, Grief, Cannibalism, Death of parent, Alcohol

Minor: Death, Racism, Xenophobia, Vomit, Death of parent

The Picture of Dorian Gray is good. I wasn’t blown away by it, but the premise is solid and I was pleasantly surprised by how audaciously queer it is. I can see why it’s considered a classic. Definitely worth a read.

Graphic: Death, Misogyny, Toxic relationship, Blood, Murder, Toxic friendship, Classism

Moderate: Addiction, Animal death, Body horror, Bullying, Drug use, Emotional abuse, Gun violence, Infidelity, Mental illness, Panic attacks/disorders, Racial slurs, Sexism, Suicide, Antisemitism, Grief, Alcohol

Minor: Animal cruelty, Body shaming, Fatphobia, Homophobia, Racism, Sexual content, Slavery, Suicidal thoughts, Torture, Violence, Xenophobia, Cultural appropriation, Colonisation

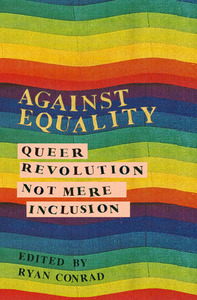

I’d definitely recommend Against Equality to anyone who considers themself progressive. It isn’t perfect, but it’s worth a read.

Graphic: Child abuse, Child death, Death, Gun violence, Hate crime, Homophobia, Pedophilia, Racism, Rape, Sexual assault, Sexual violence, Torture, Transphobia, Violence, Xenophobia, Police brutality, Murder, Lesbophobia, Sexual harassment, War

Moderate: Bullying, Confinement, Cursing, Domestic abuse, Misogyny, Sexism, Sexual content, Suicide, Terminal illness, Blood, Antisemitism, Islamophobia, Grief, Stalking, Outing, Cultural appropriation, Colonisation, Classism

Minor: Addiction, Cancer, Deadnaming, Drug use, Eating disorder, Fatphobia, Genocide, Gore, Incest, Racial slurs, Slavery, Excrement, Vomit, Medical content, Trafficking, Kidnapping, Abortion, Death of parent, Pregnancy