Take a photo of a barcode or cover

mars2k's Reviews (234)

Graphic: Death, Sexual content

Moderate: Adult/minor relationship, Alcoholism, Domestic abuse, Mental illness, Racism, Suicidal thoughts, Suicide, Toxic relationship, Violence, Blood, Murder, Alcohol, War, Classism

Minor: Ableism, Addiction, Animal death, Body shaming, Child abuse, Child death, Chronic illness, Drug use, Genocide, Gore, Gun violence, Homophobia, Infidelity, Misogyny, Pedophilia, Racial slurs, Rape, Terminal illness, Excrement, Police brutality, Grief, Pregnancy, Fire/Fire injury, Sexual harassment, Colonisation

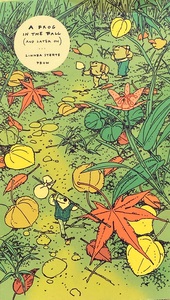

The only poem which really stood out for me was “(fenomenología)/(phenomenology).” Other than that, they all kind of blended together, and they just didn’t land for me outside a few interesting turns of phrase here and there. I think I might have enjoyed the book more were my Spanish not so rusty – the Spanish versions of the poems seemed to flow much better than the English ones.

Moderate: Death, Gun violence, Self harm, Transphobia, Violence, Blood, Medical content, Murder

Minor: Animal death, Cursing, Drug use, Genocide, Racism, Sexual content, Suicidal thoughts, Suicide, Terminal illness, Xenophobia, Excrement, Vomit, Antisemitism, Grief, Abortion, Pregnancy, Abandonment, Alcohol, Colonisation, War

The State and Revolution is, in a word, authoritative. Lenin clearly knew what he was talking about when it comes to Marxism, and I can’t deny he’s got some charisma. I feel I gained a more robust understanding of Marxism, though the writing was quite repetitive and filled with petty aspersions. It’s not something I’d go out of my way to recommend but if you’re already planning on reading some of Lenin’s works, this is a good place to start.

Moderate: Slavery, Violence, Colonisation

Minor: Ableism, Death, Drug use, Sexism, Sexual assault, Blood, Police brutality, Pregnancy, War

He’s excessively hung up on this idea that communism isn’t possible yet or wasn’t possible until very recently. The thing is, you need to make it possible. Sitting around waiting for communism to come to you is such a waste of time. I know it sounds harsh to call it counter-revolutionary but I don’t know how else to describe it.

Fully Automated Luxury Communism does not live up to its title. It’s accessible, I’ll give it that. It’s not the worst book I’ve ever read but, whether you’re a seasoned leftist or someone new to radical politics, it’s not really worth your time.

Moderate: Ableism, Animal cruelty, Animal death, Cancer, Child death, Death, Terminal illness, Excrement, Medical content, Fire/Fire injury, Alcohol, War

Minor: Cursing, Racial slurs, Racism, Slavery, Suicide, Violence, Xenophobia, Blood, Antisemitism, Dementia, Colonisation

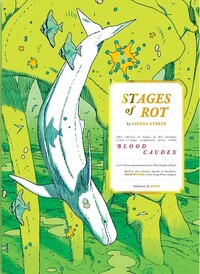

Stages of Rot paradoxically invites and rejects interpretation, and I love it for that. I’d recommend it purely for the art, but I also think there’s more literary substance to it than some give it credit for.

Moderate: Animal death, Death

Minor: Body horror, Gore, Violence, Blood, Fire/Fire injury, War

Moderate: Animal death, Death

Minor: Cursing, Violence, Blood, Alcohol

Does Dune deserve four and a half stars? Probably not. Am I going to give it four and a half stars anyway? You bet. It’s not beyond criticism (far from it) but I thoroughly enjoyed it nonetheless. I’m curious to see where the story goes from here and I’ve already ordered Dune Messiah, but I won’t be reading it just yet because I have quite a backlog of unread books to work through first.

Graphic: Death, Drug use, Emotional abuse, Fatphobia, Sexism, Torture, Violence, Xenophobia, Blood, Kidnapping, Grief, Death of parent, Murder, Injury/Injury detail

Moderate: Ableism, Addiction, Body horror, Child abuse, Genocide, Gore, Incest, Misogyny, Pedophilia, Racism, Rape, Sexual content, Sexual violence, Slavery, Suicide, Schizophrenia/Psychosis , Pregnancy, Sexual harassment, Colonisation, War

Minor: Alcoholism, Animal death, Child death, Gun violence, Homophobia, Self harm, Excrement, Islamophobia, Cannibalism, Fire/Fire injury, Alcohol

“I use the word “arbitrary” here because imaginative geography of the “our land–barbarian land” variety does not require that the barbarians acknowledge the distinction. It is enough for “us” to set up these boundaries in our own minds; “they” become “they” accordingly, and both their territory and their mentality are designated as different from “ours.” To a certain extent modern and primitive societies seem thus to derive a sense of their identities negatively. [...] Yet often the sense in which someone feels himself to be not-foreign is based on a very unrigorous idea of what is “out there,” beyond one’s own territory. All kinds of superstitions, associations, and fictions appear to crowd the unfamiliar space outside one’s own.”

Graphic: Racism, Sexism, Sexual content, Xenophobia, Islamophobia, Colonisation

Moderate: Gore, Misogyny, Racial slurs, Antisemitism, Cultural appropriation, War

Minor: Body horror, Cancer, Child death, Cursing, Death, Genocide, Homophobia, Self harm, Sexual violence, Slavery, Suicide, Terminal illness, Torture, Blood, Excrement, Murder, Alcohol

There’s not much to dislike about Create Dangerously but it’s not that deep. Perhaps Camus’s observations were more impressive in the 1940s and 50s but now they seem quite plain.

Moderate: Gun violence, Sexism, Slavery, Violence, Police brutality, War

Minor: Death, Genocide, Racial slurs, Racism, Sexual assault, Torture, Xenophobia, Blood, Murder, Fire/Fire injury, Colonisation

There are so many issues I could pick apart but I think I’ll stop here. Between the flat characters, the lack of follow-through on interesting concepts, and the inconsistencies throughout, Phoenix Extravagant is hard to recommend. That said, it’s largely inoffensive. I appreciate what the author was going for, at least, even if it feels half-baked. I don’t think it’s bad but I’m glad I’m done with it.

Graphic: Confinement, Cursing, Death, Panic attacks/disorders, Sexual content, Violence, Xenophobia, Blood, Murder, War

Moderate: Animal cruelty, Animal death, Gun violence, Misogyny, Racism, Sexism, Torture, Excrement, Vomit, Police brutality, Grief, Stalking, Fire/Fire injury, Alcohol, Colonisation, Injury/Injury detail

Minor: Ableism, Drug use, Gore, Infidelity, Suicidal thoughts, Suicide, Terminal illness, Medical content, Kidnapping, Cannibalism, Death of parent, Abandonment