Take a photo of a barcode or cover

mars2k's Reviews (234)

Graphic: Child abuse, Death, Emotional abuse, Homophobia, Grief, Outing

Moderate: Animal death, Terminal illness, Blood, Death of parent, Murder

Minor: Domestic abuse, Hate crime, Physical abuse, Torture, Violence, Kidnapping, Cannibalism, Stalking, War

Squire isn’t bad but it could have been better. Both the art and the writing needed further development. I can’t bring myself to give it a higher rating because it feels so incomplete. I’ve seen other reviewers wondering if there’ll be a sequel and while the idea that every piece of media needs to be transformed into a series frustrates me to no end, I do understand where this yearning/speculation is coming from. It does feel like there should be more. Squire is similar to Locatelli’s Persephone in a lot of ways – good and bad. Persephone’s execution was just a tad better.

Moderate: Bullying, Cursing, Racism, Violence, Xenophobia, Blood, Fire/Fire injury, Colonisation, War, Injury/Injury detail

Minor: Child abuse, Death, Torture

This book is over forty years old now, yet it remains infuriatingly relevant. It’s powerful and incisive – I would recommend reading it if you haven’t already. I can see why Angela Davis is such a celebrated writer, and I’m eager to read her other famous book, Are Prisons Obsolete?, when I get the chance.

Graphic: Death, Domestic abuse, Genocide, Gun violence, Hate crime, Infertility, Misogyny, Physical abuse, Racial slurs, Racism, Rape, Sexism, Sexual assault, Sexual violence, Slavery, Torture, Violence, Xenophobia, Murder, Sexual harassment, Classism

Moderate: Ableism, Child abuse, Child death, Confinement, Gore, Infidelity, Sexual content, Blood, Police brutality, Trafficking, Grief, Abortion, Death of parent, Pregnancy, Fire/Fire injury, Injury/Injury detail

Minor: Cancer, Miscarriage, Suicide, Terminal illness, Medical content, Medical trauma, Suicide attempt, Alcohol, Colonisation, War

Would I recommend Caliban and the Witch? Yes, I think so. Perhaps it would be best to buy a second hand copy or borrow it from a library if you’re uncomfortable giving money to this particular author, but I don’t think it’s a book that ought to be avoided outright. It’s interesting, I learnt a lot from it, and I’d consider it a solid demonstration of Marxist feminism.

Graphic: Death, Homophobia, Misogyny, Physical abuse, Racism, Sexism, Slavery, Torture, Violence, Blood, Antisemitism, Colonisation, Classism

Moderate: Ableism, Animal cruelty, Animal death, Body horror, Child abuse, Child death, Confinement, Domestic abuse, Genocide, Gore, Infidelity, Racial slurs, Rape, Sexual assault, Sexual content, Sexual violence, Slavery, Excrement, Medical content, Trafficking, Cannibalism, Abortion, Murder, Pregnancy, Fire/Fire injury

Minor: Incest, Infertility, Mental illness, Suicide, Transphobia, Police brutality, Islamophobia, Kidnapping, Grief, Abandonment, Alcohol, War

Graphic: Animal cruelty, Animal death, Body horror, Death, Domestic abuse, Emotional abuse, Misogyny, Physical abuse, Racism, Rape, Sexual content, Sexual violence, Violence, Blood, Medical content, Grief, Stalking, Car accident, Pregnancy, Sexual harassment

Moderate: Child death, Cursing, Fatphobia, Gore, Mental illness, Pedophilia, Self harm, Suicide, Torture, Murder, Fire/Fire injury, War, Injury/Injury detail

Minor: Addiction, Drug use, Genocide, Gun violence, Racism, Excrement, Kidnapping, Death of parent, Schizophrenia/Psychosis , Alcohol

The more I think about Persephone, the more I’m paradoxically both delighted and disappointed. Overall, it’s a solidly good book – don’t get me wrong. Even if some political aspects feel un(der)addressed, I actually really like that there’s a lot to think about. It’s far more interesting than I thought it’d be, and it’s definitely a book I would recommend.

Moderate: Mental illness, Violence, Blood, Kidnapping, Death of parent, War

Minor: Ableism, Confinement, Self harm, Slavery, Grief, Injury/Injury detail

Red and Blue make purple, and this prose sure is purple. Every. Single. Sentence. Is trying so hard to be poetic and deep. Metaphors are great and all but this is just too saturated with them to make any real sense. The characters and their relationship didn't feel especially substantive to me. I like the combination of spirituality and science fiction and there’s some neat imagery here and there, but for the most part I found This Is How You Lose the Time War to be a confusing mess and nothing more.

Graphic: Death, Self harm, Blood

Moderate: Animal death, Body horror, Suicide, Violence, Grief, Murder, War

Minor: Adult/minor relationship, Child abuse, Child death, Confinement, Cursing, Drug use, Gore, Gun violence, Mental illness, Sexual content, Torture, Toxic relationship, Vomit, Medical content, Stalking, Alcohol, Colonisation, Injury/Injury detail

Also,

I’d recommend Axiom’s End to fans of Stephenie Meyer’s The Host. It has a similar vibe.

Graphic: Confinement, Genocide, Self harm, Suicide, Violence, Blood, Medical content, Kidnapping, Stalking, Injury/Injury detail

Moderate: Cursing, Death, Drug use, Gore, Panic attacks/disorders, Racism, Sexual content, Antisemitism

Minor: Ableism, Addiction, Alcoholism, Animal cruelty, Animal death, Child abuse, Gun violence, Slavery, Torture, Toxic relationship, Xenophobia, Excrement, Vomit, Islamophobia, Grief, Car accident, Murder, Fire/Fire injury, Abandonment, Alcohol, Colonisation, War

The discussion of overpopulation also made me a little wary. Take this quote, for example: “Yes there are too many humans to sustain the planet, but the moment we need to decide who reproduces and who doesn’t, we enter dubious moral territory.” She does note that eugenics is “dubious moral territory” which is an understatement but at least she recognises that there are ethical issues to be considered. That’s good. But then what’s this about “the moment we need to decide who reproduces and who doesn’t”? Do we “need” to do that? I don’t think overpopulation is nearly as pressing a matter as some people make it out to be – we have the resources to feed and house everyone, it’s just that those resources aren’t effectively distributed (largely due to capitalism). I don’t know... I feel like any line of thinking that starts by taking an ecofascist talking point at face value is going to lead to some pretty rancid philosophy.

The Ahuman Manifesto is an odd book. I’m not sure what I was expecting and I’m not sure what to make of what I read either. It was interesting, I suppose, but I don’t think I’d recommend it. Three stars, just about.

Graphic: Death, Sexual content

Moderate: Ableism, Animal cruelty, Animal death, Body horror, Cursing, Genocide, Misogyny, Racism, Rape, Sexism, Sexual violence, Slavery, Suicidal thoughts, Suicide, Violence, Cannibalism, Murder

Minor: Addiction, Child abuse, Drug use, Homophobia, Terminal illness, Torture, Xenophobia, Blood, Abortion, Death of parent, Cultural appropriation, Colonisation, War, Injury/Injury detail

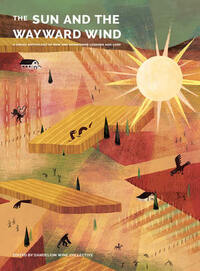

The Sun and the Wayward Wind

Akshay B. Varaham, Ivan Kasof, Aglennco, Sunita Balsara, Paloma Hernando, Mickey Walls, Ann Xu, Hannah Schwartzkopf, Raven Warner, Celia Lowenthal, Madeline McGrane, Febi Sobowale, Emily Roberts, C.J. Walker, Vreni Stollberger, Jasmine Walls, Cynthia Cheng, Sunmi, Ashanti Fortson, Sarah Webb, E. Jackson, Haley Kasof, Megan Kelchner, Olivia Stephens, Sage Coffey, Iris Monahan, Caroline Dougherty, Soumya Dhulekakr

Graphic: Fire/Fire injury

Moderate: Animal death, Body horror, Racism, Xenophobia

Minor: Cursing, Death, Terminal illness, Blood, Stalking, Death of parent, Murder, Alcohol, Sexual harassment