Take a photo of a barcode or cover

mars2k's Reviews (234)

Omnia Sunt Communia: On the Commons and the Transformation to Postcapitalism

Massimo De Angelis, Massimo de Angelis

I don’t know... It’s not a bad book per se but I feel like I didn’t get much from it. Hopefully someone else will enjoy it more than I did.

Moderate: Gun violence, Racism, Xenophobia, Police brutality, Classism

Minor: Ableism, Child death, Death, Drug use, Genocide, Homophobia, Sexism, Sexual content, Slavery, Suicide, Violence, Blood, Excrement, Islamophobia, Mass/school shootings, Car accident, Murder, Alcohol, War

A vital resource for those new to mutual aid and activism, as well as those who have been involved for a while – we all have room to improve, and this book is full of good insights and prompts.

Graphic: Violence, Police brutality, Fire/Fire injury, Classism

Moderate: Ableism, Addiction, Misogyny, Racism, Colonisation

Minor: Alcoholism, Child abuse, Chronic illness, Confinement, Cursing, Death, Domestic abuse, Drug use, Gun violence, Mental illness, Panic attacks/disorders, Self harm, Sexism, Terminal illness, Transphobia, Xenophobia, Medical content, Trafficking, Murder, Sexual harassment, Injury/Injury detail

Others of My Kind: Transatlantic Transgender Histories

Michael Thomas Taylor, Alex Bakker, Rainer Herrn

I think the best way to exemplify the cisness of this book is this: it talks a lot about trans people taking the time to educate cis people, including their doctors, and they frame this as a wonderful kindness that we ("we") ought to be grateful for, rather than actually reckoning with the fact that trans people are expected to be well-spoken experts and ambassadors who will perform emotional labour at the drop of a hat, else we be denied basic rights like access to healthcare.

Despite its flaws, however, I am glad this book exists. I did learn a thing or two about early 20th century trans culture, and about pioneering trans individuals of the era. And for that, I think Others of My Kind was worthwhile.

Graphic: Ableism, Homophobia, Misogyny, Sexism, Transphobia, Violence, Police brutality, Medical content, Outing

Moderate: Biphobia, Deadnaming, Pedophilia, Racism, Rape, Self harm, Sexual assault, Sexual content, Sexual violence, Suicidal thoughts, Suicide, Forced institutionalization, Cultural appropriation, Dysphoria, Classism

Minor: Addiction, Adult/minor relationship, Alcoholism, Animal cruelty, Cancer, Death, Drug use, Genocide, Infidelity, Racial slurs, Terminal illness, Torture, Blood, Antisemitism, Murder, Pregnancy, Lesbophobia, Alcohol, Colonisation, War, Injury/Injury detail

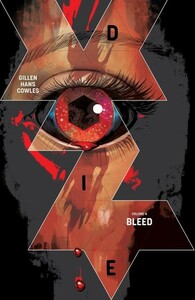

I bought this book for its stunning cover. The artwork inside isn’t quite as beautiful, but it’s expressive and full of character. It’s clear that a great deal of care has gone into the designs – from the characters to the architecture to the props and vehicles. It’s a well-crafted graphic novel all round :)

Moderate: Confinement, Death, Infidelity, Violence, Blood, Abandonment, Alcohol, War, Injury/Injury detail

Minor: Ableism, Animal death, Drug use, Gun violence, Sexism, Suicidal thoughts, Pregnancy, Colonisation

Considering I’ve spent so long picking apart The Goblin Emperor’s flaws and shortcomings, you may be surprised to hear that I did enjoy the book. It’s well-written, it’s compelling, and though there are some aspects which irked me, it’s a good book overall. Though the story isn’t great and the political assertions are dubious, I appreciate Maia so much I can’t bear to give this book a low rating. I probably won’t read the rest of the trilogy, but I don’t regret reading this.

Graphic: Bullying, Child abuse, Death, Emotional abuse, Misogyny, Physical abuse, Racism, Self harm, Sexism, Suicide, Violence, Blood, Kidnapping, Grief, Death of parent

Moderate: Ableism, Alcoholism, Body shaming, Homophobia, Terminal illness, Xenophobia, Murder, Fire/Fire injury, Alcohol, Injury/Injury detail, Classism

Minor: Adult/minor relationship, Animal cruelty, Child death, Domestic abuse, Fatphobia, Incest, Infertility, Miscarriage, Panic attacks/disorders, Sexual assault, Sexual content, Suicidal thoughts, Pregnancy, Sexual harassment, War

Graphic: Genocide, Slavery, Violence, Colonisation

Moderate: Death, Misogyny, Racism, Sexism, Sexual violence, Xenophobia, Antisemitism, Cannibalism, Murder, War, Classism

Minor: Ableism, Gun violence, Rape, Sexual content, Suicide, Blood

I don’t think Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution is as good as The Conquest of Bread, personally, even though a lot of people say it’s better. I can say this much: I appreciate what Kropotkin was going for.

Graphic: Death, Racial slurs, Racism, Slavery, Violence, Kidnapping, Cannibalism, Colonisation

Moderate: Ableism, Animal death, Child death, Genocide, Sexism, Terminal illness, Murder, War

Minor: Gun violence, Incest, Infidelity, Rape, Suicidal thoughts, Torture, Blood, Pregnancy, Fire/Fire injury, Abandonment

Graphic: Death, Misogyny, Racism, Sexism, Xenophobia, Blood, Murder, Abandonment, Colonisation, Injury/Injury detail

Moderate: Ableism, Animal cruelty, Animal death, Body horror, Child abuse, Child death, Confinement, Gore, Gun violence, Mental illness, Suicidal thoughts, Terminal illness, Violence, Cannibalism, War

Minor: Emotional abuse, Fatphobia, Incest, Infidelity, Self harm, Sexual content, Slavery, Suicide, Torture, Mass/school shootings, Fire/Fire injury, Gaslighting, Alcohol

Graphic: Ableism, Body shaming, Child abuse, Death, Mental illness, Misogyny, Sexism, Xenophobia, Blood, Kidnapping, Grief, Stalking, Fire/Fire injury

Moderate: Animal death, Child abuse, Child death, Confinement, Domestic abuse, Drug use, Racism, Slavery, Suicidal thoughts, Torture, Violence, Death of parent, Murder, Alcohol, Sexual harassment, Injury/Injury detail, Classism

Minor: Animal cruelty, Body horror, Fatphobia, Infidelity, Pedophilia, Rape, Sexual content, Suicide, Terminal illness, Transphobia, Cannibalism, Pregnancy, Abandonment, Colonisation

Graphic: Cursing, Death, Violence, Suicide attempt, Murder, Abandonment, Alcohol

Moderate: Alcoholism, Gore, Infidelity, Self harm, Blood, Grief, Cannibalism, Fire/Fire injury, Injury/Injury detail

Minor: Addiction, Biphobia, Body horror, Cancer, Child death, Gun violence, Misogyny, Racism, Torture, Transphobia, Vomit, Medical content, Medical trauma, Death of parent, War